Kapany’s breakthrough lay in the application of 'cladding'.

Narinder Singh Kapany is the visionary physicist whose pioneering work in fibre optics laid the foundation for the high-speed digital world we inhabit today.

While the likes of Steve Jobs and Tim Berners-Lee often dominate the narrative of the information age, it was Kapany’s ground-breaking research in the 1950s that physically enabled the internet to span the globe.

He took a concept that many scientists dismissed as impossible, the bending of light, and transformed it into the backbone of modern communications and medical imaging.

From the humble classrooms of Northern India to the cutting-edge boardrooms of Silicon Valley, his journey is a testament to intellectual defiance and innovation.

We explore the life of the man who captured light in glass, ensuring that his immense contribution to technology and culture is recognised with the gravity it deserves.

Challenging the Straight Line

The story of fibre optics begins not with a complex equation, but with a moment of youthful rebellion in Dehradun, India.

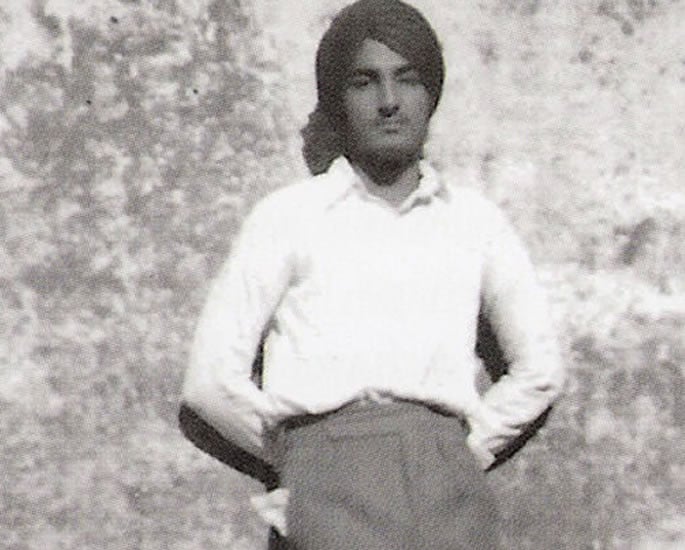

Born in Moga, Punjab, in 1926, Narinder Singh Kapany was raised in a family that valued education, but he possessed a curiosity that frequently put him at odds with authoritarian instruction.

The pivotal moment of his early education occurred during a standard physics lecture.

His teacher, adhering to the scientific understanding of the time, informed the class that light travels strictly in a straight line.

Kapany was unconvinced. He had spent his childhood tinkering with box cameras and observing the way light behaved through prisms and curved surfaces.

He raised his hand and challenged the assertion, asking if light could be guided around corners.

The teacher, dismissive of the interruption, told the young Kapany he was wrong and should focus on his studies.

For many students, a public reprimand would have stifled their curiosity. For Kapany, it was a catalyst.

He took the teacher’s denial as a personal challenge, harbouring a silent determination to prove that light could, under the right conditions, be flexible.

This obsession followed him through his undergraduate studies at Agra University and his brief service as an officer in the Indian Ordnance Factories Service.

However, post-independence India, while brimming with potential, did not yet possess the advanced optical laboratories required to test his radical theories.

In 1952, seeking the tools to prove his childhood intuition, Kapany departed for London. He arrived at Imperial College, a prestigious hub of scientific discovery, ready to confront the laws of physics head-on.

Imperial College London

London in the 1950s was a hotbed of scientific innovation, and Imperial College was at its centre.

It was here that Narinder Singh Kapany began his PhD under the mentorship of Dr Harold Hopkins, a formidable figure in the world of optics.

Hopkins was interested in transmission, but it was Kapany who provided the practical genius to make the theory work.

The challenge was immense: scientists had known since the mid-19th century, thanks to experiments by Daniel Colladon and John Tyndall, that light could be trapped in a stream of water.

However, transmitting high-quality images through flexible glass strands over a distance remained scientifically elusive.

The primary obstacle was leakage. When light hit the edge of a glass fibre, it would scatter, losing intensity and clarity.

Kapany’s breakthrough lay in the application of ‘cladding’. He reasoned that if he coated the glass fibre with a layer of transparent material possessing a lower refractive index, the light would be forced back into the core. This phenomenon is known as Total Internal Reflection.

By trapping the photons inside the core, the light could bounce zig-zag along the fibre, effectively flowing around curves without escaping.

In 1954, Kapany and Hopkins published their findings in the renowned journal Nature.

The paper, titled ‘A Flexible Fibrescope, using Static Scanning’, was a watershed moment in physics.

Kapany had successfully bundled thousands of glass fibres together to transmit an image from one end to the other, even when the bundle was bent. He had done the impossible: he had bent light.

This invention laid the immediate groundwork for the fibrescope, a medical device that allowed doctors to see inside the human body without major surgery.

While the world of telecommunications was still decades away from utilising this for data, Kapany had forged the key that would eventually unlock the Information Age.

Entrepreneurship and the Nobel Controversy

With his doctorate secured and his reputation growing, Kapany looked westward to the United States.

He moved to Rochester, New York, in 1955, before eventually settling in the San Francisco Bay Area. It was here that he truly bridged the gap between academic theory and commercial reality.

In a 1960 article for Scientific American, he coined the term “fibre optics”. He was no longer just a researcher; he was an evangelist for a new era of technology.

Kapany’s career in America was characterised by a relentless entrepreneurial drive. He founded Optics Technology Inc. in 1960, taking the company public in 1967, a rarity for an Indian immigrant in that era.

He later founded Kaptron Inc. in 1973, which he eventually sold to TE Connectivity.

Over his lifetime, he amassed more than 100 patents, covering everything from solar energy collection to biomedical instrumentation. He was a ‘Silicon Valley’ pioneer before the region had even earned the moniker, demonstrating that a scientist could also be a titan of industry.

However, his scientific legacy was marred by what many consider a significant oversight.

In 2009, the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Charles K Kao for “groundbreaking achievements concerning the transmission of light in fibres for optical communication”.

While Kao’s work in the 1960s was indeed crucial for long-distance data transmission (specifically addressing glass purity), it was Kapany’s 1954 work that proved the medium was viable.

The exclusion of Kapany from the Nobel committee’s decision sparked debate within the scientific community.

Kapany himself addressed the snub with characteristic dignity, noting that while the omission was disappointing, the widespread application of his work was a reward in itself.

Faith, Art & Philanthropy

Science was the engine of Narinder Singh Kapany’s life, but his Sikh heritage was the fuel.

He defied the stereotype of the singular, obsessive scientist by cultivating a rich life deeply rooted in the arts and spirituality.

He was fiercely proud of his background and dedicated much of his fortune to ensuring that Sikh culture was understood and respected on the global stage.

In 1967, he established the Sikh Foundation in Palo Alto, California, a non-profit organisation dedicated to preserving Sikh heritage.

Kapany was also a world-class art collector.

He spent decades assembling one of the finest private collections of Sikh art in existence, rescuing historical artefacts that might otherwise have been lost to time. He did not hoard these treasures; he shared them.

He organised major exhibitions at institutions such as the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Smithsonian in Washington DC, introducing millions to the intricate beauty of Sikh artistry.

His philanthropy extended to academia, where he endowed chairs in Sikh Studies at several prestigious universities, including the University of California throughout the state.

He authored books on Sikh philosophy and art, viewing his scientific work and his spiritual life as interconnected.

To Kapany, the precision of physics and the depth of spirituality were both searches for the truth.

When the Indian government posthumously awarded him the Padma Vibhushan in 2021, it was a recognition of a man who had successfully straddled two worlds.

He was an American innovator who never forgot his Punjabi roots, and a man of science who remained deeply devoted to his faith.

Narinder Singh Kapany passed away in December 2020, leaving behind a world that is inextricably linked by the threads of glass he helped create.

Every high-speed download, every endoscopic procedure, and every instant global communication serves as a silent tribute to his persistence.

He proved that even the most rigid laws of nature could be challenged by a curious mind.

Kapany’s legacy is not merely in the patents he filed or the companies he founded, but in the example he set: that a boy from Moga could challenge a teacher’s textbook and, in doing so, illuminate the entire world.