“Everything is technically logged and monitored."

When Albania announced in September 2025 that it had appointed an artificial intelligence system as a cabinet-level minister, it immediately grabbed global attention.

The system, named Diella, was declared “Minister of State for Artificial Intelligence” and positioned as a weapon against corruption in public procurement.

Supporters framed it as bold innovation. Critics dismissed it as political theatre.

What sits beneath the headlines, however, is a revealing case study of how governments are beginning to embed AI into the core of the state.

Diella’s appointment was a world-first.

It also triggered a wider debate about transparency, accountability and how far artificial intelligence should be allowed to shape public decision-making.

Albania’s experiment is less about replacing humans and more about signalling intent, but it raises questions that governments everywhere will soon have to confront.

A Symbolic Appointment with Practical Ambitions

Diella was elevated to ministerial status by Prime Minister Edi Rama to underline his government’s commitment to tackling corruption and modernising the state.

Public procurement was chosen as the focus for a reason.

Government contracting accounts for roughly one-third of public spending worldwide and is widely recognised as a corruption risk.

Rama framed Diella as an impartial watchdog:

“Diella never sleeps, she doesn’t need to be paid, she has no personal interests, she has no cousins, because cousins are a big issue in Albania.”

The message was clear: technology, unlike people, could not be swayed by favouritism.

In practice, Diella’s powers are far more limited than the title suggests.

The system has not been deployed as an autonomous decision-maker. Instead, it is intended to assist procurement officials at four defined stages: drafting terms of reference, setting eligibility criteria, establishing price ceilings and verifying submitted documents.

At every stage, a human expert signs off on the recommendations.

Enio Kaso, director of AI at Albania’s National Agency for Information Society, which developed Diella with Microsoft by fine-tuning a version of OpenAI’s GPT model, said:

“Everything is technically logged and monitored.”

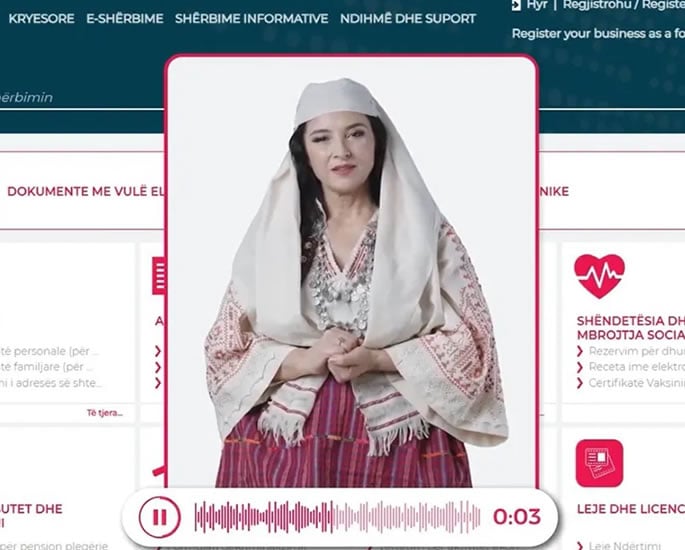

Before becoming a minister, Diella operated as a chatbot on the e-Albania platform, helping citizens access public services.

Across nearly one million interactions, it has issued more than 36,000 official documents.

Global Momentum Behind Government AI

Albania’s move did not happen in isolation. Governments worldwide are accelerating AI adoption to cut bureaucracy and improve efficiency.

By the end of 2024, US federal agencies reported more than 1,700 uses of AI, ranging from summarising documents to reviewing regulatory comments.

That figure has since climbed beyond 3,000.

Cary Coglianese, a law professor at the University of Pennsylvania who studies AI in government, said:

“I think it’s inevitable.

“As the public is more acclimated to its use in private settings, everything from choosing what movies to watch on Netflix to helping them with their homework, there’s likely to be much more acceptance, and maybe even demand.”

Political leadership has helped drive that shift. In the US, accelerating AI use is framed as central to delivering “the highly responsive government the American people expect and deserve”.

In the UK, estimates suggest AI assistants could save taxpayers up to £45 billion by improving public sector efficiency.

Coglianese argues that AI adoption is desirable if systems can outperform humans against clear criteria, but warned:

“There can be irresponsible, careless, or negligent implementation and use of AI by governments, which should be criticised and deplored.”

As systems move from assisting decisions to making them, scrutiny, transparency and public involvement become critical.

Transparency, Trust & Unresolved Concerns

In Albania, those safeguards remain a point of contention.

Kaso said: “We have one key objective.

“Making everything as transparent and as explainable as possible.”

While Diella’s data is stored in a secure environment, details about how citizens will scrutinise its recommendations in procurement processes remain unclear.

Georg Neumann, of the Open Contracting Partnership, said:

“There’s been very little transparency around what exactly the AI is presenting.”

His organisation acknowledges recent improvements in Albania’s procurement reforms but stresses that public communication will determine whether trust follows.

Coglianese said: “If I were advising a government. I’d say let’s set up a public process of input.”

Legal challenges have also followed. Albania’s opposition has questioned whether a non-human entity can hold a constitutionally defined public function.

Rama has since clarified that responsibility for Diella’s creation and operation rests with the prime minister’s office, reinforcing that ultimate authority remains human.

For now, Diella’s role is closer to that of an advanced assistant than a true minister.

Rama added:

“By creating the world’s first AI minister, Albania is not merely embracing the future, but trying to do its part in designing it.”

“Diella is far from being a gimmick.”

Despite the rhetoric, Diella is not governing Albania. It is helping to structure information, standardise processes and signal political intent.

Coglianese expects AI reliance in government to grow steadily, though unevenly.

“Some countries may move too fast in this area, risking some kind of real catastrophic failing,” he says, pointing to cybersecurity and poor system design as potential brakes on adoption.

Albania’s initiative sits at the intersection of innovation and symbolism.

It highlights how AI can support reform in areas like procurement while also exposing the risks of overselling technology as a cure-all.

Whether Diella becomes a meaningful governance tool or remains largely emblematic will depend on transparency, oversight and public engagement.

For now, power remains firmly in human hands.

But as AI systems improve and public familiarity grows, Albania’s early experiment may be remembered less as a novelty and more as a glimpse of how governments test the boundaries of digital authority.