It embodies India’s idolisation of whiteness.

Colourism remains one of Bollywood’s most controversial issues, defining beauty standards for generations on the big screen.

It is a form of prejudice against people with darker skin tones, with a preference towards fairer complexions within the same racial group.

Colonial ideas of whiteness and its superiority laid the roots for colourism, associating fairness with authority, status, and desirability.

In Bollywood, colourism is most visible in casting, where fairer actors dominate more lead roles.

On the other hand, darker-skinned actors have been typecast into background roles or characters of lower status.

Due to Bollywood’s popularity, many fans may internalise this bias, preventing them from questioning the lack of inclusivity in films.

While recent films attempt to challenge this underrepresentation, systematic change appears to be slow and inconsistent.

Yet these changes sit within an industry where colourism continues to shape who is seen and celebrated.

Fairness As The Default

Bollywood’s obsession with fair skin is often linked to longstanding social hierarchies associated with the caste system.

The association of light skin with moral superiority is visually evident through costumes, lighting, and most predominantly, casting.

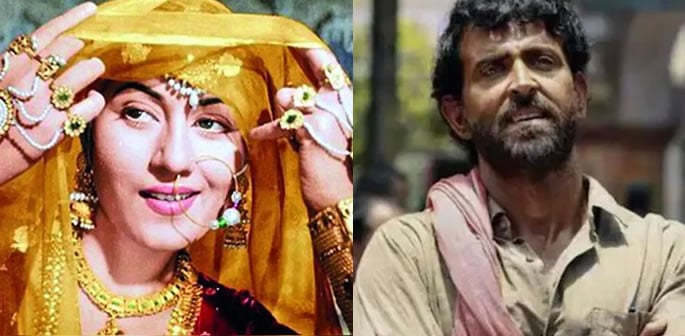

Mughal-e-Azam (1960) illustrates this unfair bias, with light-skinned actors like Prithviraj Kapoor playing the roles of royalty, embodying nobility and wealth.

Madhubala played Anarkali, a dancer who falls in love with the prince in this film. According to the late actress Minoo Mumtaz, Madhubala’s “complexion was so fair and translucent”.

This casting demonstrates a desire to adhere to beauty standards over cultural accuracy, especially as Anarkali is one of the main characters.

In Chandni (1989), Sridevi’s fair appearance was heightened by Yash Chopra’s use of clothing, symbolising elegance and femininity.

Chandni (Sridevi) frequently wore white clothing to represent her innocence and purity, an iconic fashion statement that reignited the appeal of fairness.

Many actresses were measured against these standards, linking skin colour to the value of a film’s cinematography.

In an interview with Hindustan Times, Richa Chadha discussed the discomfort created by Bollywood’s skin-colour standards when auditioning for roles.

She said:

“Once I was rejected for a role because the director insisted on having a ‘fair and homely’ actress.”

Bollywood’s pursuit of fairness was too overwhelming for Priyanka Chopra, who said that her “skin had been lightened in many movies, through makeup and lighting”.

These early portrayals establish fairness as a symbol of femininity, heroism, and virtue.

At the same time, dark-skinned actors portrayed characters who were morally ambiguous, of lower caste groups, and villains, creating a concerning precedent.

These restrictions are embodied by Nawazuddin Siddiqui, who found he was typecast as a criminal.

He stated: “I was getting roles where I was always getting beaten… sometimes I played a thief, sometimes a pickpocket.”

In Siddiqui’s debut film, Sarfarosh (1999), he had a minor role as a criminal who had come under police scrutiny.

Yet repeated casting such as this is disempowering for darker actors like Siddiqui.

Although colourism is mainly enforced through makeup or casting, Gori Tere Pyaar Mein (2013) supposedly uses visual effects and marketing to reflect this bias.

The film’s title references light skin through ‘gori’, drawing immediate attention to skin tones.

Although naturally fair, it appeared as though Kareena Kapoor’s face was lightened on posters.

Not only does this set unrealistic standards, but it also highlights the industry’s obsession with accentuating an actor’s fair appearance.

By putting fair characters at the heart of this film’s marketing, Bollywood ensures such complexions continue to define desirability and profitability.

Despite raised awareness of this inequality, Bollywood’s bias for lighter skin remains a common practice.

Issues with Brownface

Brownface is one of the most performative portrayals of colourism.

This practice includes actors darkening their skin with makeup to imitate and stereotype dark brown communities.

It embodies India’s idolisation of whiteness.

This racial distinction highlights how deeply such prejudices are rooted and the vast projections of these ideals.

Brownface is a common method in Bollywood, with major actors like Hrithik Roshan participating in this in films such as Super 30 (2019).

In Super 30, Roshan plays a mathematician who sets up a programme to coach students for free.

The film is based on Anand Kumar’s life, showcasing his financial struggles and commitment to making education accessible for students living in poverty.

Kumar is from Bihar, where many live below the poverty line.

The irony is striking since Super 30 addresses the harsh reality of class inequality, yet it refuses to cast authentically, undermining itself.

Whilst many dark-skinned actors are eager to enter Bollywood, this industry prioritises fairer and more famous individuals over authentic casting, a resistance to true inclusivity.

This prioritisation is evident when Amitabh Bachchan was cast as Iqbal, a working-class porter from a rural background, in Coolie (1983).

Though initially considered dusky, Amitabh’s stardom gave him opportunities to play characters of a darker skin tone than his.

This reflects Bollywood’s resistance to casting dark-skinned actors, alongside the power of fame.

In Coolie, Amitabh’s skin was heavily darkened with bronzing makeup to signal his character’s working-class background.

Brownface exaggerates the dehumanising stereotypes surrounding darker individuals, whilst also exposing its reluctance to challenge these inequalities.

Filmmakers appear unwilling to risk box-office success by giving darker-skinned actors opportunities to display their talents.

This apprehension is maintained with the success of Super 30, with CNN reporting it as one of the 25 highest-grossing Bollywood movies of 2019.

A conflict between what is financially viable and authentic casting is reinforced, showing how deeply racial bias is embedded within the industry, choosing to rely on established, fair-skinned performers.

Until dark-skinned actors are given leading roles that focus on a character’s attributes rather than appearance, diversity will remain disingenuous.

Impact of Colour, Class and Gender

Colourism signifies something deeper than beauty standards, as it is interlinked with class and gender hierarchies.

To appeal to higher social classes, the caste hierarchies remain embedded within Bollywood’s casting decisions. Actors with darker complexions are limited to supporting and background roles, objects of ridicule and unfavourable treatment through their moral inferiority.

For example, Chennai Express (2013) casts darker actors as henchmen. Vijay Jasper, who played one of Sathyaraj’s henchmen, was used for comedic purposes in the film.

But his character is mocked for his rugged appearance and dramatic behaviour.

Jasper embodies the silliness of the roles given to darker actors, presenting such characters as humorous, yet inferior and foolish.

There are further inconsistencies within the casting as Deepika Padukone plays a Tamil heroine, Meenamma, yet her relatives are played by dark-skinned actors.

Although the family members authentically reflect their South Indian roots, Deepika’s fairer skin reinforces feelings of exclusivity.

The invisibility felt by this community is degrading, positioning them as unimportant within Bollywood.

In contrast, fair-skinned actors are at liberty to play the hero/heroine, framing them as aspirational, desirable, and romantic.

This disparity is evident in Ankur (1974), a film that follows the harsh reality of Lakshmi’s life as she endures poverty and social marginalisation.

Shabana Azmi plays Lakshmi and has a naturally darker complexion. She was chosen to illustrate how people with darker skin tones are associated with lower-caste positions within society.

The film emphasises Lakshmi’s vulnerability when sexually exploited.

It confronts audiences with ways prejudice operates for people like Lakshmi, one of the first films connecting skin tone with socio-economic oppression.

More contemporary films like Article 15 (2019) also use physical appearances to raise awareness of societal marginalisation.

Ayan (Ayushmann Khurrana) is an officer investigating the murders of Dalit girls, yet his search for justice is halted by corrupt authorities who discriminate against lower-caste citizens.

Despite rules in place to prevent cast-based discrimination, the film reveals the prevalence of double oppression for darker individuals of lower classes.

It also exposes how caste and skin tone exacerbate a person’s social inequality, raising awareness of the inhumanity of this situation.

Films Challenging Colourism

Despite widespread bias, more films have been resisting Bollywood’s obsession with fairness.

I Am Kalam (2010) demonstrates such inclusivity by casting two dark-skinned actors as male leads without attempting to edit their complexions.

The casting is both realistic and natural, placing no extra emphasis on the diverse cast.

Instead, it explores important issues surrounding child labour, discrimination against lower-class families, and the necessity for change.

The film centres around Chhotu, an intelligent boy who dreams of breaking the cycle of poverty and becoming educated.

It challenges Bollywood norms by casting a darker actor as the hero of the story, rather than the villain.

I Am Kalam proves that protagonists can be authentically dark skinned and move audiences through powerful acting.

It won many awards, including the Filmfare Award for Best Story, signifying a turning point for Bollywood.

Placing darker actors in lead roles will not undermine the success of the film, so such concerns should no longer influence casting decisions.

In 2015, Nil Battey Sannata was released and starred Swara Bhasker, a woman of medium complexion.

Although no darker actress was cast, Swara’s more favourable skin tone was not overly glorified or the focus of the film.

Instead, the film only explored a mother’s unending love for her daughter as she strives to prove the importance of education.

It presents the transformative effects of ambition, resilience, and female strength, rather than the potency of female beauty and fairness.

Although darker-skinned actors had smaller parts in this film, their characters did not hold questionable virtues or morals, a step in the right direction.

Films such as these mark a turning point, replacing the pursuit of fairness with more truthful portrayals of Indian identity.

Colourism in Bollywood is not just a question of beauty, but a reflection of privilege, visibility, and power.

The preference for fair skin sustains a hierarchy that isolates many, preventing them from showcasing their talent.

Here, casting decisions are not defined by acting ability so much as they are by appearance, a discrimination still prevalent in today’s Bollywood.

These patterns demonstrate how colourism still shapes the stories Bollywood feels most comfortable putting forward.

Shifts in modern films illustrate a willingness to question what true inclusivity looks like.

Bollywood’s future lies in recognising the importance of representing its audience in all its diversity.