"It was about creating a new identity for Asians in the UK"

Bhangra music may have introduced itself to British culture during the 1980s and 90s, and with it came different subgenres, including Bhangra-Reggae.

This represented the point where traditional Punjabi folk collided with the bass-heavy rhythms of the Afro-Caribbean diaspora.

This genre was the direct result of shared urban spaces, racial solidarity, and a creative rebellion against both Western marginalisation and traditionalist domestic expectations.

During the 1980s and 1990s, this fusion transformed from an experimental underground sound into a global cultural export that redefined what it meant to be young, British, and Asian.

By examining the evolution of this music, one gains insight into the socio-political landscape of post-war Britain and the resilience of immigrant communities.

We detail the history of Bhangra-Reggae, the sound’s key architects and the lasting impact it had on a generation navigating a complex dual identity.

From Punjab to the Midlands

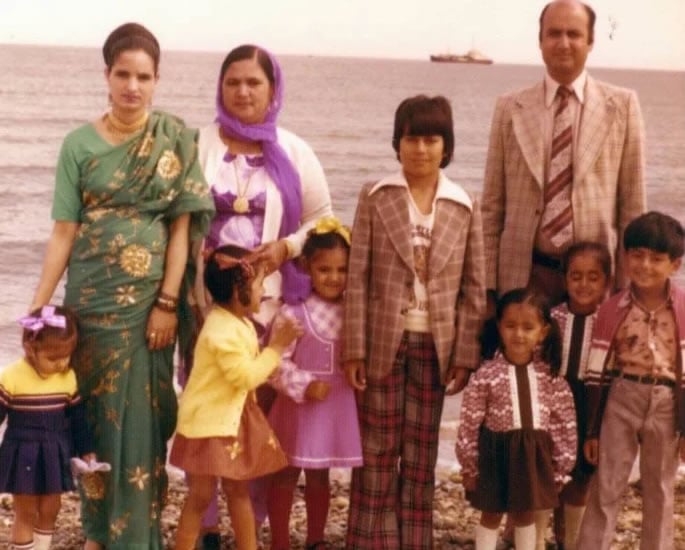

The foundations of Bhangra-Reggae were laid in the 1960s, a decade defined by the arrival of Sikh families from the Punjab region of India.

These migrants were primarily drawn to the UK by industrial labour opportunities, finding jobs in the metal foundries of Birmingham and the burgeoning transport sectors of London.

They brought with them the dhol and the traditional songs of Bhangra, a high-energy folk dance originally performed by men to celebrate the harvest festival of Vaisakhi.

In its traditional form, the music was a vital consolation for former farmers who had traded the lush agricultural valleys of Punjab for the grey, industrial landscape of Britain.

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, the children of these immigrants began to redefine their heritage.

This second generation grew up in multicultural inner-city wards where South Asian families lived alongside Afro-Caribbean communities.

This proximity facilitated a natural exchange of cultural capital; the pulsating bass lines of reggae and the rhythmic poetry of hip-hop began to permeate the ears of young Punjabis.

As they looked for ways to assert their presence in a country that often viewed them as outsiders, they found a kindred spirit in Reggae’s themes of resistance.

The dhol beat, with its inherent syncopated swing, found a perfect partner in the “one-drop” rhythm of reggae.

This synthesis was the birth of Bhangra-Reggae, a musical process that allowed British South Asians to honour their roots while embracing their urban British surroundings.

For the early Punjabi community, the evolution of Bhangra into a British fusion served as a primary tool for this identity formation and mental well-being.

The Underground Resistance of the Bhangra Daytimer

By the mid-1980s, Bhangra-Reggae was flourishing, yet it faced a significant domestic hurdle: access to nightlife.

Many British South Asian youths were raised in conservative households where late-night clubbing was strictly forbidden.

This social restriction birthed the “Daytimer” phenomenon – underground discos held in the middle of the afternoon.

These events allowed students to “bunk” school or college, immerse themselves in the music, and return home in time for dinner, their parents unaware of their attendance.

Bradford became the epicentre of this movement, providing a space where the “sexless, studious” stereotype of Asian youth was dismantled.

These daytime discos were radical spaces where a new British Asian identity was forged.

Rani Kaur, better known as DJ Radical Sista, was a prominent figure in this scene.

Speaking to the BBC, she noted: “At the time, there was very little in terms of Asian cultural stuff in the mainstream; we would get the odd programme on TV but it was more geared to the older generation.

“There was a gap and there was a thirst for something to fill it, so daytimers just rocketed.

“It was about creating a new identity for Asians in the UK that had not existed before.

“Bhangra records were very hard to get hold of, you could get Bollywood but Bhangra was hard to get hold of so these were the only places you could go to hear it regularly.”

The scene allowed for a fusion of aesthetics, where “Bhangra-muffin” style, blending the rude boy culture of reggae with traditional Punjabi flair, became the standard.

This movement provided a vital sense of agency.

For British South Asians, the daytimer was a space where they did not require the validation of the white mainstream. It was a self-contained ecosystem of corner shops, cassette tapes, and community halls.

By creating their own social spaces, the youth of the 1980s successfully managed the stresses of the diaspora and the pressures of “dual identity”.

Architects of the Sound

While the daytimer scene provided the environment, specific visionaries provided the soundtrack.

In the early 1990s, Birmingham-based producer Bally Sagoo emerged as a pivotal figure. Sagoo’s upbringing was steeped in black music, from soul to hip-hop, which he blended seamlessly with traditional Punjabi folk.

His 1991 compilation, Star Crazy, is cited as the catalyst that put British Bhangra on the global map.

The track ‘Mere Laung Gawacha’, featuring Rama and Reggae artist Cheshire Cat, epitomised the genre’s potential.

He said: “This particular track was a Punjabi-Reggae song, it was an experiment, where the Asian kids went crazy and everybody thought we need some stuff like this.”

Being more of a DJ and not a musician himself, Sagoo experimented with samples and produced a sound that included catchy Reggae bass lines.

A lot of his music was recorded at Planet Studios in Coventry where he was supported by the likes of Tom Lowry in terms of production.

In Birmingham, artists like Apache Indian produced by Simon and Diamond came to the fore with a “Bhangra-muffin” style.

Raised in Handsworth, he became the first artist to take Reggae with Punjabi lyrics into the mainstream British charts with hits like ‘Boom Shack-A-Lak’ and ‘Arranged Marriage’.

His music tackled social issues within the community, set against authentic dancehall rhythms.

Psychological Resilience and the Dual Identity

Bhangra-Reggae’s impact extended beyond the dancefloor; it served as a tool for psychological resilience.

Navigating a dual identity, being “too Asian” for British society and “too Western” for traditional parents, often led to a sense of cultural homelessness.

Music provided the bridge, validating the lived experience of the diaspora.

Other artists who contributed to this sound in their own way were Stereo Nation, Raghav and The Sahotas.

By the mid-1990s, as the British Asian population expanded, Bhangra remained the force that held these communities together.

However, regional differences in the sound began to emerge.

In the BBC documentary, Pump Up the Bhangra: The Sound of Asian Britain, Bobby Friction noted:

“The eighties London sound was a bit more innovative, open to Hindi and other Asian music, whereas Birmingham was Desi because the community was solid, Punjabi and Sikh.

“It had an authentic rawness whereas London’s was more poppy popular.”

This “authentic rawness” was what allowed the music to resonate so deeply with youth who felt marginalised by the “poppy” mainstream.

The legacy of this music continues to protect the well-being of the community by providing a historical narrative of success and integration.

Modern British Asian artists who sample grime or drill owe a direct debt to the pioneers of Bhangra-Reggae.

The subgenre stands as a testament to the fact that cultural fusion is a survival mechanism.

It allowed a generation to reclaim their narrative and find pride in their heritage, ensuring that the heavy bass of the reggae rhythm and the sharp crack of the dhol would forever be synonymous with the British Asian identity.

The story of Bhangra-Reggae is ultimately one of integration without the loss of heritage.

It represents a period in British history where the children of immigrants took the tools available to them, the sounds of their neighbours and the songs of their ancestors, to build a cultural home.

From the early experiments in Birmingham to the heights of the MTV generation, the genre proved that multiculturalism is a living, breathing musical reality.

It bridged the gap between a British upbringing and Indian heritage, offering a harmonious blend of sounds that reflected a bicultural experience.

Today, the influence of this movement persists, serving as a reminder of the power of artistic innovation and the universal language of music in fostering community and identity.