It came to be an integral part of South Asian identity and presence

Bhangra music in Britain, a wave of music based on traditional Punjabi music, emerged in certain cities in the late 20th-century.

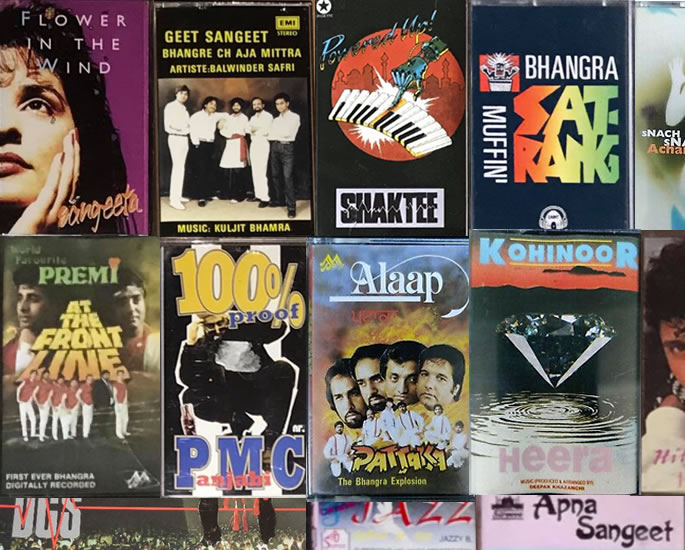

The UK has been the home to many legendary Bhangra artists and bands such as Alaap, Heera, Malkit Singh, Apna Sangeet, DCS, Safri Boys, The Sahotas, Panjabi MC and many many more.

However, British-born Bhangra is much more than just a genre of music. The music was created as many bands and artists claim to help preserve identity and culture.

The growing popularity of this music during its prime era between the 80s and 2000s led to it becoming part of British Asian identity and culture for those from South Asian communities.

The differences in British culture and South Asian culture led to this music creating an identity, especially for those with a desire to affiliate with the Desi way of life.

Over three generations South Asians, born and bred in Britain, faced an identity crisis between these two vastly different cultures.

Often, British Asians have to negotiate between the two norms and choose when to ‘be British’ or when to ‘be Asian’.

However, British Bhangra music acted almost as a thread between the two cultures.

Interestingly, the 90s is considered a golden age for British Asians. It was a period when the concept of a bicultural identity was truly developing.

Music specifically allows individuals to create both their individual and collective identities.

British Bhangra music was essential in aiding the creation of a bicultural identity for British Asians in the late 20th-century.

DESIblitz explores the legendary genre that was British Bhangra. We look at how Bhangra became a glue between two cultures especially during the 1980s-2000s.

The Need for a Distinct Culture

The South Asian diaspora has been in Britain for many centuries. However, the boom came within the post-War years when many families from South Asia settled in Britain.

The post-War years witnessed a youthquake, which in fact ‘encompassed the explosive discovery of teenage identity’.

Subsequently, this meant that the late 20th-century witnessed the emergence of distinct teenage cultures for the first time.

Most notably the Teddy Boys, Mods, Rockers, Skinheads, Punks and Goths. All of which had their own distinct style, music, image and values.

These youth subcultures used popular culture as an outlet for shaping and expressing their individual and collective identity.

These post-War youth cultures tended to include more white people, rather than people of colour.

Following post-War immigration, the British youth were ethnically diverse, therefore British youth culture was bound to reflect this.

However, Mike Brake, in his 1980 book The Sociology of Youth Culture and Youth Subcultures proclaimed:

“Asians are rarely found in youth culture.”

This is a misconception. Just because South Asians were not found in traditional British youth culture does not mean that they were immune to youth culture.

Trying to Break Through

South Asians’ lack of presence in traditional British youth culture could be in part due to the social fabric of South Asian families.

The outwardness of some post-War youth cultures would not have aligned with traditional South Asian norms of honour and modesty.

In 1977, Roger and Catherine Ballard published a study on the development of Sikh settlement in Leeds, UK.

Within their work, they interviewed a Sikh girl from Leeds who asserted that:

“I’ve learnt to be two different people.

“I’m quite different when I’m away at college with English people than when I’m here with my family and my Punjabi friends.

“I don’t have any trouble getting along with English people, but I suppose though that I’m really Punjabi at heart.”

She continued:

“Sometimes I get very depressed when I’m at college. I long to go home and be Indian”

Considering this, it was inevitable that second-generation immigrants in the late 20th-century would form their own culture.

An identity and culture which allowed them to “be Asian” and “be British” simultaneously.

Being born into a South Asian family and brought up in western society does not mean sacrificing one identity for another.

Due to this, there was a need for a distinct British Asian identity and culture. A culture that combined tradition and modernity and this is where Bhangra comes into play.

The Development of British Bhangra

Traditional Bhangra

In 1893 the Punjabi Gazette published an article on Bhangra, stating:

“In the spring, up to 1st Baisakh when the wheat is filling in the ear, the Jats gather at the daira nightly to dance and sing.

“At the end of each verse the audience join in the chorus, dancing all the time. The dance is known as Bhangra.”

Traditional Bhangra, which consisted of a vibrant communal song and dance, developed in the 19th-century in West Punjab, which is now part of Pakistan.

Bhangra is popular for its distinctive beat, which consists of the dhol, as well as its traditional boliyan (verses).

This lively traditional song and dance are said to have drawn its name from Bhang, better known as a drink made with spices, milk, and copious amounts of ground cannabis.

Bhang was traditionally available and consumed during festivals during ‘Baisakh’, the month of the harvest in India.

Hence, the word Bhangra is said to have come from the lively dancing and celebrations to Punjabi folk songs whilst ‘high’ on Bhang.

Everything about Bhangra was lively, in particular, the dance and song accompanied by vivid colourful clothing.

Originally, Bhangra represented regional Punjabi identity and became an integral part of expressing Punjabi culture.

However, Bhangra dance began to formalise on a national level following independence in 1947.

Regional folk groups performed on national celebrations, such as Republic Day in India as well as the many Bhangra competitions held in India.

This was the original form of Bhangra associated with dancing.

However, in Britain, Bhangra in its music form derived from those who had migrated to give Punjabi music a new license and identity in Britain.

Bhangra in Britain: 1970s-1980s

Following immigration to Britain, Bhangra, along with the individuals that performed it, had relocated to Britain by the late-60s.

This led to a number of Bhangra dance groups forming and performing during the 70s and early 80s.

These groups such as Taranga Group, Nachda Sansar, and many more, were part of the entertainment offered at festivals, cultural shows and weddings.

The dance form of Bhangra even spilt over into universities and colleges, where Bhangra dance groups competed with each other at cultural events organised by British Asian students.

This is something that continued to be popular amongst British Asian students and youth into the 2000s.

During the 70s, the migrants who came from Punjab with an interest in songs and music formed some of the earlier Punjabi music bands.

These included New Stars, Red Rose, Anardi Sangeet Party, Bhujangy Group, Ashoka, Anokha, Awaaz, International Group, Milap, Andaz, Geet Sangeet and many more.

They mainly performed traditional Punjabi songs at weddings and functions which were attended by mostly men in pubs. This was the start of what became the sound of Bhangra.

The arrival of East African Asians in the 70s also contributed to the sound of Bhangra. Especially those from Punjabi and Gujarati backgrounds.

The forward-thinking ways of these communities introduced a new outlook towards the music form of Bhangra.

The fusion of western sounds with traditional instruments used in Punjabi music created a sound that got labelled as Bhangra music.

Pioneering Bhangra music producers and musicians such as Kuljit Bhamra and Deepak Kazanchi helped formulate this sound to create the identity of Bhangra music for the masses.

This fresh beat and music included sounds of the traditional dholak, tabla and dhol fused with drums, electric keyboards and guitars.

The 1980s was the golden age for Bhangra music, it was a period where British Bhangra was truly born.

Many Bhangra music bands formed during this period, all with the motivations to preserve the Punjabi language and Desi culture in Britain.

In particular, many bands formed in London and the West Midlands areas.

However, the forerunners of this new sound were the Southall group, Alaap.

Alaap were an extremely popular band within the 80s.

With the Punjabi lyrics, western beats and Channi Singh’s unique voice, Alaap became a major hit in the 80s.

Traditional Bhangra songs were usually Punjabi folk songs. However, British Bhangra songs often changed their themes to love, to fit their new British Asian audience.

Alaap were hugely successful with hits such as ‘Bhabiye ni Bhabiya’ and ‘Teri Chunni De Sitare’.

In particular, lead singer, Singh, is often praised for “pioneering modern Bhangra music around the globe.”

A 2017 article by the BBC coined them as the “most prolific” Bhangra band, while a 2007 BBC article highlighted how lead singer Channi Singh was:

“Recognised as the Godfather of Punjabi Bhangra music in the West.”

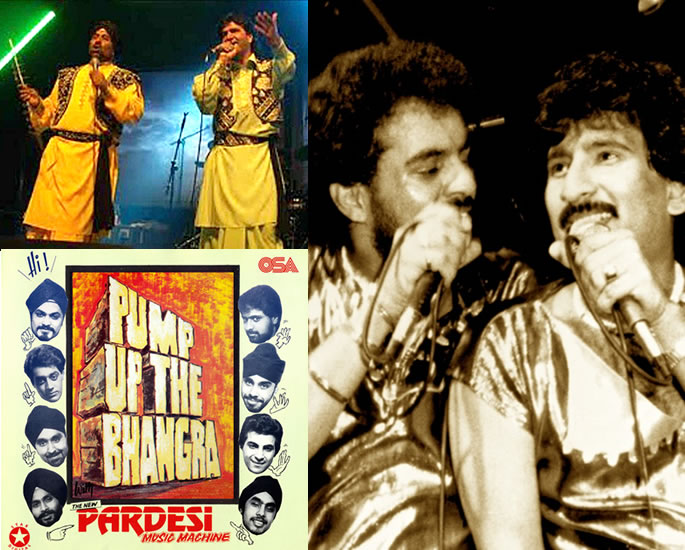

During this time, the West Midlands became a hub for the formation of popular Bhangra bands. These included Malkit Singh (Golden Star), Apna Sangeet, DCS, Achanak, Pardesi and Azaad.

Songs by these bands were massive hits and very popular among the Bhangra music loving fans.

Malkit Singh (Golden Star) had major hits with songs such as ‘Gur Nalo Ishq Mitha’ and ‘Kurri Garam Jayee’.

Apna Sangeet led by singers Sardara Gill and Kulwant Bhamra got known as a band who were very close to communities and were massively popular at weddings.

Their tracks ‘Nach Paya Mutiara’, ‘Nach Nach Kudiaye’ and ‘Boliyan’ were hit dance-floor songs.

‘Tenu Kaul Ke Sharaab’ Wich and ‘Bhangra’s Gonna Get You’ were notable hits for DCS.

Hit songs for Azaad included ‘Kabaddi’, ‘Peeni Peeni Peeni’ and ‘Mohabbat Hogai’.

Pardesi’s album ‘Pump Up The Bhangra’ became a huge success and featured some incredible production work with the use of samples with singers Silinder Pardesi and Boota fronting the band.

These bands were key in Bhangra’s development as a culture and identity, as they were the pioneers behind spreading the unique sound that was British Bhangra.

They were key in changing the face of Punjabi music and creating a new innovative modern sound for British Asians. They broke cultural barriers and paved the way for future Bhangra artists.

Another popular London Bhangra band during this time was Heera, led by singer Jaswinder Kumar and Palvinder Dhami, it was formed in 1979 in Southall.

Kuljit Bhamra produced Heera’s first hit album, Jago Wala Mela.

Hit songs like ‘Melna De Naal Ayee Mitro’ and ‘Teri Akh De Ishare’ put Heera firmly on the UK Bhangra map.

Deepak Khazanchi who joined the band worked on their album’s Diamonds from Heera and Cool & Deadly.

In a 1987 NME article, a member of Heera, expressed:

“We want more West Indian and English people to appreciate and respect our sound, to realise that it’s not just ding-dong curry music anymore.”

These comments epitomise the development of Bhangra in Britain. These bands were truly sewing a thread between British and Asian cultures for the first time.

West London band, Premi, also gained a great deal of popularity during this period.

They came into the forefront in 1983 with their album, Chhamak Jehi Mutiar, produced by Kuljit Bhamra.

Some of Premi’s popular songs include ‘Mein Tere Hogayee’ and ‘Jago Aya’, as well as ‘Nachdi Di Gooth Khulgaye’, which are still fondly played by DJs.

The abundance of artists, bands and Bhangra producers during this time clearly shows how British Bhangra music was really coming into a right of its own during the 80s.

It emerged as a distinct modern genre of Punjabi music produced in Britain which was hugely followed by British Asians who now had a ‘go-to sound’.

Bhangra in Britain: Late 1980s-1990s onwards

The fusing of Bhangra with western music did not just stop in the 80s. The 1990s emerged as a very strong era for this British born sound.

This period highlighted how the music continued in its post-80s development.

Bhangra music started blending Caribbean and African American genres of hip-hop, reggae and rap with its songs.

Much of the earlier British bhangra songs were in Punjabi, however, the later songs had Punjabi verses intertwined amongst English.

One of the reasons for the fusion of South Asian music with these other genres was the fact many British Asians grew up influenced by these other sounds.

The music and beat of this period began to epitomise what it was like being South Asian in a multicultural environment.

Popular artists and bands during this era include The Sahotas, Satrang, Shaktee, Anakhi, Eshara, Geet The Megaband, Safri Boys, Jazzy B, RDB, Sukshinder Shinda, B21 and many more.

The Sahotas popularised their ‘Sahota Beat’ with songs such as the hugely popular song ‘Hass Hogia’ and ‘Sahota Show Te Jake’.

They performed on mainstream TV shows like Cilla Black’s ‘Surprise Surprise’, ‘Blue Peter’ and ‘8:15 from Manchester’.

The Safri Boys, formed by Balwinder Safri in 1990, was a legendary British Bhangra band.

Their first claim to fame was the first-ever hit Bhangra music single in the UK, called Legends which featured the blockbuster track ‘Par Linghade’.

Amongst many of their hit albums including Bomb the Tumbi and Another Fine Mess, their notable smash album was Get Real, which was number one in the BBC Derby Aaj Kal show Bhangra charts for a huge 10 weeks.

Songs like ‘Chan Mere Makhna’ and ‘Rahaye Rahaye’ are still heard today on dance floors and radio stations.

Canadian, Jazzy B was also a massive hit in the British Bhangra scene during this period. Influenced hugely by Kuldeep Manak, he collaborated with other Bhangra artists such as Sukhshinder Shinda on a number of albums, including Gugiyan Da Jora (1993).

This era of this genre of music in the UK also opened doors for female singers who joined the scene. Popular singers like Sangeeta and Channi Singh’s daughter Mona Singh gained huge traction among fans.

The 1990s was the time in Bhangra music when change was inevitable.

With boy bands being a popular entity in the west such as Take That and the Back Street Boys, this also influenced the sound of Bhangra.

Bhangra ‘boy band’, B21, formed in 1996. Featuring Jassi Sidhu and brothers Bally and Bhota Jagpal, their name B21 originated from the Handsworth postcode in Birmingham.

They became very popular and also introduced the era of miming songs rather than always playing live and doing what got known as PA’s (Personal Appearances) at club shows and functions.

They had hit songs such as ‘Darshan’, which features on the Bend it Like Beckham (2002) soundtrack. Other popular tunes include ‘Jawaani and Chandigarh’ from their 1998 album By Public Demand.

This led the way for some other boy bands. This fusion of the 1990s created a distinct sound for British Asians that went with the times.

A sound that truly epitomised British Asian experiences of being born into a South Asian family and bred in multicultural Britain.

Innovating for the Future

One thing that has become apparent when looking at the history of British Bhangra music, is its ability to adapt and reinvent itself.

Unlike other genres of music, which tend to stay rather stagnant over the decades, Bhangra reinvented itself and moved progressively with the times.

There was an acknowledgement within the industry that if this music was here to stay it needed to change in line with the interest of its fans.

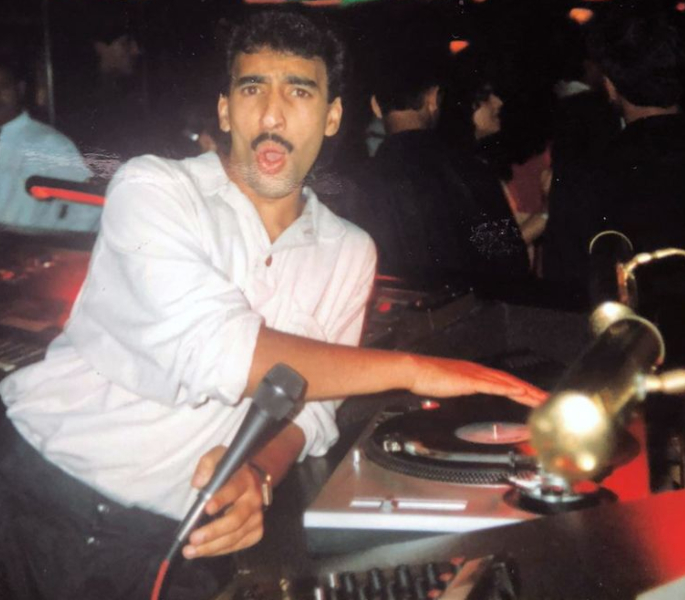

The mid to late 90s saw the emergence of the DJ era. During this era, there was a trend of remixing Bhangra songs and many DJ’s became producers.

These songs included remixes of Punjabi folk singers, traditional South Asian instruments with R&B, Rap and Hip-Hop.

This type of fusion allowed DJ’s themselves to experiment and make a distinct sound. The music was not only popular amongst South Asians, but also in the mainstream.

The DJs were hired by record companies such as Oriental Star Agencies.

The creation of this music was a lot cheaper than working with actual Bhangra bands and lots of musicians.

British Bhangra of the previous years was very much kept amongst the South Asian diaspora. However, the DJ era witnessed more of a globalisation of British Bhangra music.

This type of Bhangra is seen in popular artists such as remixing Bally Sagoo and Panjabi MC

In particular, Panjabi MC is considered a pioneer for this era of Bhangra. Rajinder Singh Rai, better known as Panjabi MC, is a British Indian producer and DJ.

In a 2012 interview with Thisis50, Panjabi MC mentioned how James Brown, Jimmy Hendricks, Bob Marley, Pink Floyd and Michael Jackson were some of his biggest musical inspirations.

His breakthrough single was the 1997 track ‘Mundian To Bach Ke’.

This song catapulted the fusion of Bhangra beats with western sounds to the mainstream fore. It is a nostalgic British Bhangra song that literally everyone would have heard!

The track combined Punjabi lyrics with a sample from the popular TV series Knight Rider theme in the music.

The song was hugely successful, it sold over 10 million copies worldwide, gaining its status as one of the bestselling singles of all time.

Within British Bhangra music, the track’s success was unlike anything that had been witnessed. It became an extremely significant song in British Bhangra.

It was the first all Punjabi lyric track to make it on BBC Radio One’s playlist. Punjabi MC also appeared on the popular BBC TV show Top of the Pops.

The Bhangra song spent 4 weeks in the national UK top 20 charts.

Panjabi MC also won many prestigious music awards for this song. From World’s Best Indian Artist at the World Music Awards, to Best UK Act at the MOBO awards.

‘Munidan To Bach Ke’ is an iconic song in British Bhangra history.

It allowed Bhangra music to become internationally recognised as an identity for South Asians.

This popularity also was recognised by American artist, Jay-Z, who asked to be featured on a remix of the track. ‘Mundian To Bach Ke’ is a track that everyone can enjoy.

Listen to this iconic Bhangra song:

Dharma Records, a London based record label, expressed how Panjabi MC’s success with this track:

“[Punjabi MC] has paved the way for the recognition and success of other new Asian artists such as Panjabi Hit Squad, Jay Sean, RDB, Metz+Trix and the production work of Rishi Rich.

“All of these artists enjoy support from the mainstream media.”

Metz + Trix are a music duo from Manchester were popular in producing a Bhangra and Garage fusion.

The band were a key voice for British Asian youth culture. Their songs contained edgy beats, catchy lyrics and bass lines.

Metz and Trix produced many chart-toppers and made a huge impact on the British Asian music scene. Some of their popular songs include ‘Aja Mahi’, ‘Sah Rukh Dha’ and ‘Bi-Lingual’.

Speaking exclusively to DESIblitz, Metz said:

“We were the pioneers of the British Asian music scene by fusing MC’ing with different styles of music like Garage, Hip Hop and Drum’n’Bass and I think we continue to do that and push the boundaries.”

RDB, a brother trio from Bradford also came into their own during this period. Their fusion of popular mainstream sounds with Bhangra beats elevated them to become a popular act.

Surj, Manjeet and their late brother Kully were the founding members of this trio. They went onto produce music for Bollywood films with a strong Bhangra element.

Films such as Heropanti, Dr Cabbie, Namastey London, Singh Is King, Kambakkht Ishq and Yamla Pagla Deewana featured their songs.

The British Bhangra sound of the music producer and DJ era was truly a sound that reflected the multicultural environment British Asians were experiencing.

Rishi Rich, Juggy D and Jay Sean were another Bhangra music collective that created songs that appealed to the new generations.

Featuring the latest electronic sounds, appealing beats and tunes with catchy but simple Punjabi lyrics. Their big hit ‘Nachna Tere Naal (Dance with You)’ released in 2003 became an anthem amongst club-goers.

Rishi Rich helped launch many new and upcoming artists during this era, including H Dhami the son of Heera groups Palwinder Dhami. His album Sadke Java released in 2008 catapulted him into fame like his father.

New singers such as Jaz Dhami and Gary Sandhu began to make headway into the UK Bhangra music scene gaining quick popularity.

New Bhangra producers subsequently took the helm to produce Bhangra music in the UK which promoted its powerful traditional rhythmic beats fused with western sounds. These included Tru Skool, Tigerstyle, PBN, Dr Zeus, Gups Sagoo and Aman Hayer.

Unlike the popular songs of previous decades, British Bhangra songs of this era were beginning to gain recognition internationally including in India, as well as in mainstream British music.

The sound of Bhangra in Britain was a truly unique genre and innovated with the times and became the sound for British Asians. The sound broke many cultural barriers.

British Bhangra music now provided Punjabi songs with a fresh new license for future generations.

A Distinct Sound

Falu Bakrania, the author of Bhangra and Asian Underground, recalled her experience of hearing a British Bhangra artist:

“One afternoon in the summer of 1991 my cousins played a remix track for me; it was Bally Sagoos ‘Star Megamix’ from the album Wham Bam: Bhangra Remixes, released in 1990 in Birmingham.

“‘Star Megamix’ was unlike anything I had heard before.”

Further asserting:

“The track brought together a range of South Asian sounds in a way I’d never heard growing up as a second-generation South Asian in the United States.”

This Bhangra and urban fusion of the late-80s and 90s was not just a new South Asian sound, but it was distinctly a British Asian sound.

Support of Radio

South Asian radio stations in the UK played an important role in the support of Bhangra music as a genre. Songs were played on many shows across the BBC network.

One show in particular that supported the sound of Bhangra massively was called Aaj Kal.

This live weekly show was broadcasted from BBC Radio in Derby and attracted huge audiences.

It promoted artists, bands and producers and launched its hugely followed weekly chart. Since there was no official chart.

Bhangra bands, singers and producers valued the support of the presenters of the show who were Satvinder Rana, Kash Sahota, Poli Tank and Nicky.

The team invited popular bands and singers to their studio and did 1-1 interviews with them to promote their latest releases.

Aaj Kal was considered a pioneer in British Asian radio and by 1988 it was the biggest radio show in Britain. It came to be an integral part of South Asian identity and presence.

Aside from the Bhangra music, the radio show also included the first-ever Asian soap opera, “Bhakra Brothers”, on the radio.

Other local BBC Radio stations, which championed Bhangra music, included Midlands Masala broadcasted from Birmingham.

Other radio stations such as Radio XL in Birmingham and Sunrise radio in London were also behind this genre of music created in the UK.

Subsequently, BBC Asian Network and other radio stations emerged to support the growing sound into the 90s and onwards.

This helped mould the identity of the music as a genre that fans could strongly related to as British Asians in South Asian communities.

A Subculture but Not Mainstream

One of the aspirations of Bhangra bands and artists was always to make this genre of music mainstream in the 1980s and early 90s. But it, unfortunately, progressed as a subculture during that time especially.

This did slightly change after UK chart hits like those of Punjabi MC in the late 90s.

Rajinder Dudrah, writing in 2007, states how:

“British Bhangra no longer suffers from the invisibility of previous decades.”

Considering the immense popularity and influence of British Bhangra music it is hard to see why it was “invisible” in its early years. British Bhangra artists did not make it into British mainstream charts.

This meant this genre of music created in Britain was not recognised fully by the mainstream and was not inclusive like other forms.

Some argue it was down to that the songs were not fully sung in English. But there were other factors as well.

Bhangra albums, produced with the same if not more effort than other genres of music, however, sadly lost out to generating income for the bands and artists.

Unlike their western counterparts who were given advances in money for producing albums for record labels and royalties for sales, South Asian record labels in the UK did not pay the same.

In fact, bands were hardly paid much for producing albums despite the popularity of their music and the force behind the sound of Bhangra in the UK.

They were often paid a lump sum which also meant they sold their rights to the labels for the recording in return.

Hence, giving the labels full freedom to sell units of cassettes, vinyl records and subsequently CDs, and make profits.

Three major labels from the period were Multitone, HMV/EMI and Oriental Star Agencies. They sold thousands of units of albums that went platinum for some of the popular bands.

One of the major problems was the sale price. Most Bhangra albums could be bought for £2.50 from a local shop that also sold music or even the market. The most was probably £5.99 for a CD.

Whereas, pop albums produced by western artists were sold at £10.99 for a CD or £5.50 for a cassette version.

Therefore, giving a ‘royalty’ from such a low amount was never going to be an option for record labels to Bhangra artists.

One of the reasons for the invisibility, Dudrah mentioned, in the mainstream music industry could also be down to where the albums were sold.

British Bhangra artists sold thousands and thousands of records; however, these were mainly brought through South Asian music shops.

Dudrah asserts:

“The sale returns from these smaller stores were not included, or even acknowledged, in the makeup of the British pop charts of the time.”

This meant that most of the famous Bhangra bands in the UK had members of bands who still had ‘day jobs’ to survive financially.

The biggest form of income for Bhangra bands and artists was weddings and functions such as ‘day timers’ or seasonal celebrations at clubs.

Weddings were the highest source and bands were charging anything from £700-1000 upwards in the 80s.

In the later stages, during the peak of Bhangra music, bands were getting paid up to £5000 or more per wedding.

In comparison, how many mainstream pop artists earned their income from weddings? Hardly any. They were paid royalties and huge sums for concerts.

This was where the exclusivity of bands and artists was not possible. Quite often, you could see a band member in a local pub having drinks amongst everyone else.

Bhangra’s popularity led to many developments, ‘some more welcomed than others, in the industry.

Prior to the noughties live Bhangra bands were often hired for weddings, however, following the DJ era of Bhangra this changed.

DJs were far cheaper and began to be preferred for weddings. DJs incorporated “a dhol player, live mixing, and an indoor firework show”.

Dudrah exclaims that this: “Brought to the fore an affordable culture of music entertainment and dancing.”

Identity in Bhangra Songs

Alongside the beat of Bhangra, the lyrics of the songs also aided the creation of a distinct British Asian identity and culture.

Dudrah elaborates saying:

“British Bhangra can be characterised as an urban anthem for many British South Asians, incorporating their pleasures, pains and politics.”

With this in mind, British Bhangra songs helped to create a linguistic, cultural and racial identity.

Linguistic Identity

When Channi Singh, lead singer of Alaap, arrived in Britain he realised that many second-generation immigrants were not in touch with their South Asian heritage.

One of the reasons Alaap’s songs were in Punjabi was because Channi wanted to help that generation to get in touch with their heritage.

This sentiment was felt by many Bhangra artists during this time. Juggy D explained the importance of a Punjabi linguistic identity:

“It’s very important for us to try and use music to pass on our Asian culture.

“When I was a kid, we only spoke Punjabi at home, but I know a lot of young Asians are not so fluent.

“We have made a real effort to try and include simple phrases in our songs.

“For us trying to maintain the Punjabi language is very important, we want to show that we are not ashamed of our culture.”

South Asian culture places a great deal of emphasis on understanding and speaking your mother tongue. However, many young British Asians do struggle with this aspect.

Yet, the fact Bhangra artists actively tried to help through their music highlights how Bhangra aided the creation of a collective linguistic identity.

Punjabi was no longer a language confined to the four walls of your home. It was something listened to and enjoyed outside the home too.

British Bhangra music provided Punjabi songs with a fresh new genre for the next generations.

British Asian is an umbrella term that cover’s many fantastic cultures, religions and languages from South Asia all residing together in Britain.

While British Bhangra songs were only in Punjabi, British Bhangra was extremely inclusive.

It did not matter if you were Indian, Pakistani or Bangladeshi, Muslim, Sikh or Hindu, everyone could enjoy the sound of Bhangra.

Bhangra was a universal music genre that broke through barriers and enjoyed by all. It truly was the “urban anthem” for British Asians coming from different South Asian communities.

Cultural Identity

Maria Pagononi, in her article Shaping Hybrid Identities: A Textual Analysis of British Bhangra Lyrics maintained:

“Bhangra spells out new exciting ways of being British.”

Bhangra allowed British Asians to be both British and Asian simultaneously.

Alongside a linguistic identity, Bhangra music also created a cultural identity in a modernised way.

Often fusing different western music styles with Bhangra to enhance its appeal to different audiences.

This is clearly heard in Apache Indian and Malkit Singh’s 1997 fusion song ‘Independent Girl’ from a mainstream album.

In particular, in the Punjabi verse of the song:

“Aaj kal di toon haigee Heer Saleti (You are today’s Heer Saleti)

Tera sadian da Ranjha main Jogi (For centuries I’ve been your Ranja Jogi)”

Here, when Malkit Singh refers to the beautiful girl in question he compares her to a modern-day ‘Heer’ and himself to ‘Ranjha’.

The celebrated legend of Heer-Ranjha is a folk love story originating from the Pakistani area of Punjab.

It is a timeless love story in Punjabi heritage that is often compared to Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.

The reference to this Punjabi cultural legend in a British Bhangra song highlights how British Bhangra was not just a ‘toothless hybrid’.

The music allowed young British Asians to discover traditional Desi roots in a modernised and youthful way. This is something that they would not have otherwise been able to do in British society.

Album Covers

It is not just the music itself that creates an identity and culture, but it is also the accompanying album covers.

Looking at the album covers from British Bhangra artists really visualises how Bhangra created a bicultural identity.

Many album covers were very creative and embodied messages in them to promote the uniqueness of the British Bhangra sound.

Bands often would be on the covers wearing their different unique looks.

Be it a western fashion to promote their residence in the UK or a hybrid look, that still connected with the sound of British Bhangra uniquely.

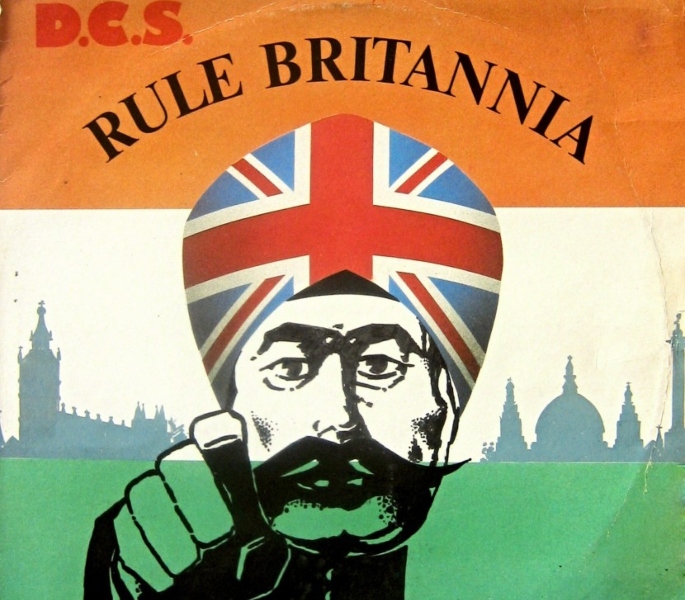

Albums from Bhangra bands such as DCS, took a different angle on displaying British Asian identity.

In 1991, Birmingham-based band DCS released the song ‘Rule Britania’. The song aimed for national racial unity and contained lyrics such as:

“We all live under the same sky the same moon so let’s dance to the same old tune.”

The album cover for this song depicts the idea of second-generation immigrants being both British and Asian.

It contains a man wearing a union jack turban, while in the same pose that’s on the WW2 propaganda “Your Country Needs You” poster.

In the background, there is the Indian flag with the outline of the London skyline in the centre.

DCS’s cover really epitomises how British Bhangra created a distinct identity and culture for British Asians. It shows how British Bhangra music combined mixed heritages and experiences.

British Bhangra music was not just a genre, but an expression of South Asian culture and identity.

Daytimer Gigs

Simply listening to Bhangra music is not enough for it to create a distinct identity and culture. The Bhangra events also aided the creation of a distinct identity and culture.

Daytimer events created a physical space for British Asians to enjoy British Bhangra music.

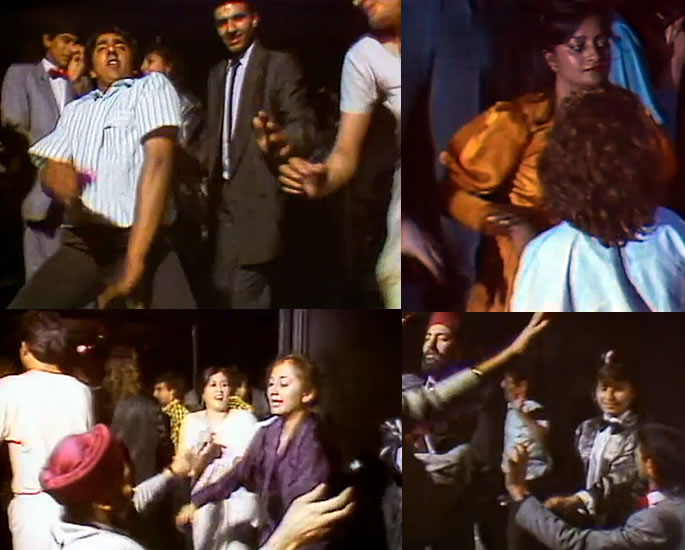

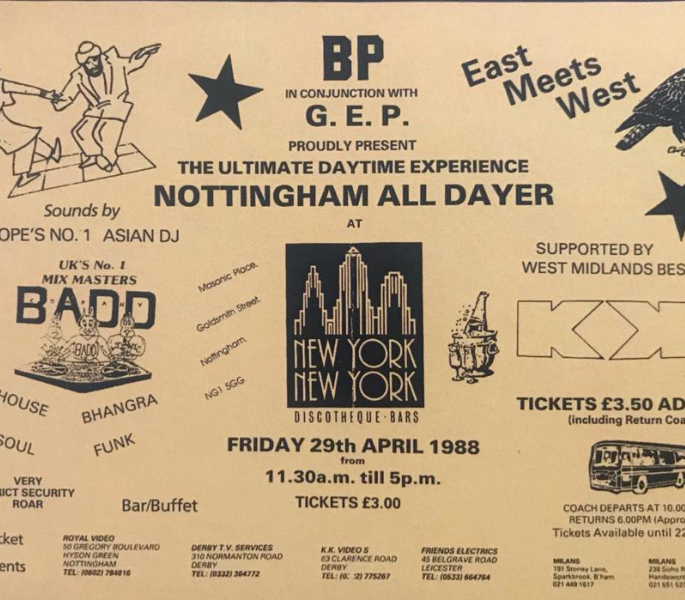

Daytimer’s, which grew in popularity in the late-1980s and 1990s, were Bhangra events that took place during school hours.

Many young British Asians used to bunk off school to attend daytime events, while their parents thought they were at school.

These events were often coined as ‘a national phenomenon’. They took place in major cities such as London, Manchester, Birmingham and Nottingham.

Dudrah emphasised the secrecy surrounding the events, by stating:

“Kids were getting on buses to go to a club where there would be 2,000 Asians dancing away. The trick was to arrive back spotless, as if nothing had happened, so you’d live to tell the tale.”

Mac, a singer in the Bhangra group Dhamaka, praises daytimer events by stating:

“The music is our music and it’s our show, not a goray (white) gig or a kale (black) show.”

This comment highlights how daytimers did not just allow British Asian youth to partake musically in British popular culture, but also spatially.

Daytimers were more about how Bhangra allowed them to have their own space in British society. A space that was just for South Asians.

Dudrah maintains:

“Daytime events allowed British Asian youth to partake in British popular culture in terms of their own needs and desires.”

It is under this context that daytime club events were born. Daytimers allowed the British Asian youth to be part of British popular clubbing culture in their own way.

A BBC Network East feature attended an Alaap daytime gig and spoke to some of the crown attending the daytime show.

A male at the gig said:

“I feel Bhangra is the in-thing at the moment and everyone wants to be part of it.

“I think Asian people got a bit fed up of listening to English music at nightclubs and they needed something to call their own.”

Aside from having an opportunity to listen to Bhangra music, a major aspect of daytimers was also hooking up.

A daytime regular, Jeevan* reveals more about this side of daytime gigs:

“Coming from a strict household, there was no way I could go out in the evenings.

“So, one way of meeting boys who were into the same music as you was by going to daytime shows.

“It gave us the chance to hook up with the opposite sex for sure!”

Bhangra daytimers gave British Asians the freedom to escape the ‘shackles’ imposed on them by parents and family.

A gig-goer at the Alaap concert said:

“A lot of students go to daytime discos because their parents object to them going to concerts like these.”

A woman at the gig said:

“I think it gives a chance to young girls to go out. Often they are not allowed to go out in the evenings.

“It’s an opportunity for them to do so in the daytime and they can participate ‘you know’ in the latest Bhangra culture as well!

A Liminal Space

Ram Gidoomal in his book Sari ‘n’ Chips made the analogy that living in a society that has a different culture to that of your parents can be like:

“Trying to play football without knowing which team you are on.”

This suggests that the two cultures and identities are competing for first place.

However, Bhangra events provided a new boundary, almost an equal playing field, in which you could negotiate both cultures simultaneously.

Falu Bakrania interviewed Bhangra music fan Krishnendu Majumdar. Majumdar supports this claim, as she stated when at Bhangra events:

“The clash of cultures in me was no longer a force pulling me apart. I was glowing and felt that this was where I belonged.”

While another Bhangra event goer, Rajan Mistry, interviewed by Bakrania asserted:

“For once, Asians can conduct themselves with other Asians in a way they would never dream of doing in front of their parents.”

This suggests that Bhangra events provided British Asians with a free space where they could be who they wanted to be.

Rajan’s and Krishnendu’s comments also suggest that Bhangra almost occupied a liminal space for British Asians.

Liminal space means ‘a corridor between two different places’ or in other words a threshold. A threshold that allowed British Asian’s to articulate their bicultural identity.

Fashion

Music is not the only thing that aids the creation of an identity.

Within other post-war British youth cultures, fashion played an integral role in distinguishing between different subcultures.

For example, the Teddy Boys had their distinct Edwardian style, while the Mods had their miniskirts.

Similarly, the British Asian’s attending Bhangra music events also had their own style and identity.

Actor and director, Riz Ahmed, speaking exclusively to The Fader, explained what would typically happen on the day of a daytimer event:

“So, you’d turn up for assembly and registration and bounce, get on the train, change your clothes.

“Coaches and busloads of people would come in from Manchester, Birmingham, Milton Keynes.”

Ahmed further explained how there was a distinct style at these events:

“People would be in their Adidas drill tops, which said ‘East to West.’

“The Pakistanis would wear the green Adidas tracksuits with the white stripes with the moon and the star on the back.

“We took a lot from garage culture.

“The girls were in Moschino, sportswear, Versace, Tommy, and Nautica, with big hair and big earrings.”

There was a great deal of secrecy surrounding these events, as British Asians were not able to openly inform their parents about them

This in turn meant that the young Asians, mainly the girls, would have had to hide their club clothes and change in the club toilets.

Fashion as an Identity

Within a BBC article, Moey Hassan, a Bhangra DJ in the late 1980s, stated:

“South Asian girls turned up in their salwar kameez with a carrier bag.”

“They’d go into the toilets and emerge wearing jeans and a leather jacket. They came out looking like Olivia Newton-John.”

Bakrania stated that British Asian’s “club gear was somewhat a uniform”. This was certainly the case, but it was not just about wearing a ‘uniform’ that your parents would disapprove of.

The changing into the daytimer clothes, clearly highlights how Bhangra music became an identity for British Asians.

This concept can be summed up by looking at Riz Ahmed’s short film, Daytimer (2014).

Set in 1999 London, the film follows Naseem, a young British Pakistani, as he skips school to attend a daytime event. Ahmed framed the film on clothing changes and spaces.

It begins with Naseem changing into his school uniform. The camera then focuses on him putting his clothes for the daytimer in his bag.

In the very last scene, Naseem is standing in his bedroom and looking at the floor. The camera then focuses on his school uniform, then his daytimer clothing, and then onto his salwar kameez.

The camera’s focus on Naseem’s different outfits, in a sense, is a focus on Naseem’s multiple identities.

If the Bhangra music events did not exist then Naseem’s only identities would have been his school uniform at school and his salwar kameez at home.

This would have meant that his British and Asian identities were kept parallel to one another.

The emphasis on spaces and clothing in the film highlights how British Bhangra aided the creation of bicultural identity in the 1990s.

Bhangra Band Fashion

Bhangra music in the UK did not just influence the fashion of the fans but of the bands too.

Costumes of Bhangra bands in the 80s and 90s became an iconic part of the movement and also created a unique identity for them as well.

Sequenced colourful shirts, white tight trousers, white socks and headbands were all part of the kind of attire worn by the groups.

Some bands wore suits with extra smart looks all accessorised with sunglasses.

Others colour coordinated themselves on stage with singers wearing different clothes compared to the rest of the band members.

Every group tried to create their individual look and tried to create a style that suited their look as well.

Some bands made it a must to wear different clothes for every major gig they attended.

Malkit Singh often wore a golden sequenced belt over his turban. Alaap and Heera were always wearing catchy coordinated outfits.

Tina a huge Bhangra fan from the 80s says:

“The Bhangra bands would not be complete without the clothes they wore on stage!”

“The costumes gave them this kind of star status to them, that made them the entertainers we all wanted to go to see.

“The music was elevated by their look and we loved to watch and dance to their music!”

Bhangra fashion, as such was thus, not just restricted to the fans and gig-goers, but also played an intricate role for bands and artists who were the representatives of the music.

Beyond Britain to Bollywood

Bhangra’s popularity also transported to Bollywood.

A lot of Bollywood films feature songs that sound very familiar.

Many of the upbeat Punjabi sounding songs in Bollywood films are in fact remixes or remakes of classic British Bhangra songs from the nighties and noughties.

Songs from bands such as Alaap and Heera were frequently copied.

The song ‘Mujhe Neend Na Aayein’ the film Dil (1990) starring Aamir Khan, was a complete copy of the Alaap song, ‘Chunni Ud Ud Jaaye’ without any permissions or rights from Channi Singh.

While the song ‘Ni Mein Sas Kutni’ from the film Ghar Aaya Mera Pardesi (1993) was a direct copy of ‘Sas Kutni’ by Heera.

This practice was common during the 80s and 90s where songs were just simply copied or reproduced without any permission from bands or artists by Bollywood music directors.

Dudrah explains that many 90s Bollywood films:

“Witnessed the cheap and hurried production of British Bhangra and Bollywood remix albums by a few opportunists.”

Bollywood began stealing many popular British Bhangra songs and often did not give them credit.

Dudrah reiterates this saying:

“In some extreme cases, the quick technological production of Bhangra and Bollywood remixed tracks is done without permission of the original artists or bands.”

The use of Bhangra songs has continued in Bollywood.

For example, the 2019 comedy film Good Newz, starring Kareena Kapoor Khan and Diljit Dosanjh, contains the song ‘Laal Ghaghra’.

It is a remake of the British Bhangra song ‘Laal Ghaghra’ by Sahara on their 2004 album Undisputed.

In 2020, the song ‘Ambarsariya’, from the 2013 film Fukrey, became a popular Tik-Tok trend amongst the South Asian diaspora.

However, much of the younger generation may not know that this version was a remake of the 2001 iconic British Bhangra song, ‘Ambersariya’ by Mac G.

These reproduced songs often result in the loss of meaning, authenticity and influence of British Bhangra songs.

Unfortunately, not much could be done about this copying in the 80s and 90s, as the small British Asian record companies would not have been able to afford the large legal bills.

However, now rights and permissions seem to be getting better due to performance royalty organisations helping stamp out this kind of misuse.

But while Bhangra music created a massive identity of culture in Britain, it was not acknowledged directly within Bollywood.

Cultural Identity of Bhangra Music

Bakrania interviewed Swati, a Bhangra event goer and he stated:

“This music wasn’t just us saying, ‘Hey we’re Asians, we exist’.

“It was saying, ‘We’re Asians, we’ve been brought up in Britain, we’ve been brought up in all different parts of Britain and we have different experiences.”

A woman at the Alaap daytimer gig said:

“Young [Asian] people in Britain feel the sense of identity.

“They feel they need to express their culture and Bhangra music allows them to understand their culture, their language and roots”

British Bhangra music epitomised the experiences of being born in a South Asian family, yet being brought up and living in a multicultural British environment.

In particular, the fusion beat and lyrics of Bhangra music acted as a platform for British Asians to construct and articulate their bicultural identity.

Bhangra also allowed the creation of a physical space in British society for British born South Asians for the first time.

It was not just a genre of music. British Bhangra music gave Punjabi music a new fresh licence for younger generations.

Hence, it was originally a way for young British Asians to discover Punjabi heritage but became to be an expression of what it meant to be both British and South Asian.

Future of Bhangra Music

Does British Bhangra music still have that overwhelming ‘power’ over its followers?

Sadly, the genre does not have the same ‘power’ as it once did with its appeal to the masses.

Perhaps the audiences who loved to help support and promote this sound from the 80s and 90s have now grown up and the newer generations do not perceive the sound of genre in the same way anymore.

Bhangra music in Britain especially performances by live bands has literally now sadly diminished.

Also, the sound of Bhangra has transformed into new waves of fusion not retaining its cultural identity in Britain as it did in the 80s and 90s.

Compared to the past, the internet has changed the way music is being made and consumed.

Video plays a massive role in the popularity of music today. This applies to Bhangra and Punjabi music as well.

YouTube views seem to dictate the popularity of songs compared to the popularity of artists.

The two common types of music produced are traditional Bhangra sounding music laced with powerful beats versus modernised Punjabi music featuring singers from Punjab.

The new sounds often use vocals sang remotely abroad by artists in India that are digitally sent to music producers as file transfers.

Then, the songs are produced using music technology in the UK, USA or Canada by producers, many of who are DJs.

Music streaming platforms like Spotify, Apple Music and Prime Music now make it possible to measure the downloads of these songs compared to fans buying albums as cassettes in the past.

This is a new era for the sound of Punjabi music which perhaps does not resonate with the original sound and cultural identity of Bhangra music, which was once created and made by bands residing in Britain.