"Bhangra music is kind of all the same, isn't it?"

Bhangra music was a refreshingly new sound that introduced itself to British culture during the 80s and 90s.

The vibrant and soulful charm that Bhangra music had provided British Asians with a genre they could relate to.

Whilst discrimination was still rife during this period, music became a uniting force.

The British underground was an example of this, showcasing the stylings of garage, reggae and Bhangra. It was here where a bicultural identity started forming amongst individuals.

Ever since the migration period in the 50s and 60s, many South Asians struggled to fit in. Did they have to be South Asian or British?

Bhangra music in Britain acted as a cord between the two cultures. People could live a western lifestyle but still learn and relate to their heritage through music.

Besides this, the actual talent and colour of Bhangra music made it a unique force at its peak. This was especially evident between the 80s and 00s – labelled as the ‘golden age’.

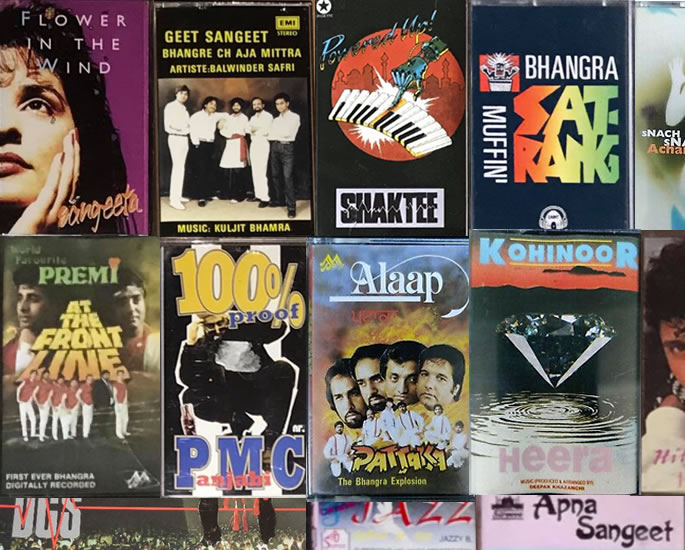

The British Bhangra scene birthed many legendary artists.

Malkit Singh, Panjabi MC, Alaap, Apna Sangeet and Sukshinder Shinda along with many more paved the way for this electrifying music.

With such a distinct sound that spread across the UK, many British Asians celebrated the success of Bhangra proudly.

However, the genre’s popularity seems to have died down compared to the thrills it experienced in the ‘golden age’.

That’s not to say Bhangra music is totally extinct, but does it hold the same weight amongst British Asians? DESIblitz explores.

Past Popularity

With Bhangra music, the focus was placed on a type of band culture which meant the genre was much more about all the musicians involved.

Previously with folk music, it was the singers who got all the attention. However, Bhangra was heavily influenced by the subcultures of Britain.

Genres like rock and even the migration of East African Asians in the 70s contributed to how Bhangra evolved within the UK.

It was an entirely new sound. New melodies were created and the use of the tabla, dhol, guitars, keyboards and drums formed fresh songs.

Pioneering this new wave was the likes of Malkit Singh, who was part of the group Golden Star. Their tracks ‘Tootak’ (1988) and ‘Jind Mahi’ (1990) were monumental.

As well as Malkit, there was the trailblazing group, Alaap. Their lead singer Channi Singh was coined as the godfather of Punjabi Bhangra music.

The Sahotas were also popular around this time. They formed alternative genres with Bhangra to represent all the different identities floating around.

They also broke through on mainstream TV, taking part in shows like Blue Peter and 8:15 from Manchester.

Moreover, Bhangra was sending shockwaves through the charts.

Get Real (1994), the smash album from the iconic band, Safri Boys, was number one for 10 weeks in the BBC Derby Aaj Kal show Bhangra Charts.

Additionally, Canadian artist Jazzy B, a household name everywhere was also a massive hit in British Bhangra.

His youth spoke to the younger crowds but his artistic qualities resonated with the elder generations.

The scene was booming.

Classical folk instruments were barely used, and the integration of synthesisers, Caribbean music and African American sounds resonated with the masses.

In the 90s, Bhangra music started to incorporate more English verses as well. This along with the influence of other genres captured the essence of being British Asian.

All those growing up around that period were impacted by other cultures and communities.

Therefore, Bhangra epitomised life as a British Asian existing in a multicultural environment.

That’s what made it such a popular and euphoric genre.

From there, it went on to be a global phenomenon with artists such as Panjabi MC innovating the game.

His 1997 track ‘Mundian To Bach Ke’ was a huge success, selling over 10 million copies and spending four weeks in the UK Top 20 Charts.

It also reached the likes of American mogul, Jay Z, who jumped on a remix of the track.

Even iconic producer, Timbaland has sampled many Bhangra songs and doesn’t shy away from showing his appreciation of it.

More modern artists started to emerge on the Bhangra scene. Rishi Rich, Juggy D and Jay Sean brought a more RnB-type feel that appealed to younger generations.

Iconic releases like ‘Nachna Tere Naal (Dance With You)’ (2003) were even played in clubs across the country.

Furthermore, artists such as Jaz Dhami and Garry Sandhu continued to fly the flag for Bhangra music.

Their superb songs such as ‘Theke Wali’ (2009), ‘Bari Der’ (2009) and ‘Main Ni Peenda’ (2011) provided that same bubbly feeling as their predecessors.

With such a deep-rooted and rich history, it’s no wonder why Bhangra music was such a sensation around the world.

Amongst British Asians, it gave them a catalogue of memories and joy. From the music itself to events like ‘daytimer’ parties, Bhangra music was a catalyst movement for British Asians.

Movement Away

As music diversified, more British Asians were exposed to other types of music, most notably American rap and British pop.

Likewise, those who witnessed the prime of Bhangra in the 80s and 90s have grown up. So, new generations aren’t apparent to what Bhangra personified during that period.

Also, the need for live bands and the importance of audience interaction diminished – two factors which British Bhangra was built upon.

Social media, the internet and streaming services have also contributed to a shift away from this genre.

Popularity is based upon views and therefore Bhangra finds it hard to retain the identity it fought so hard to build.

But, artists themselves are also focusing on other areas of music. Fusing genres is still very much alive, but it’s more Punjabi songs and hip hop that are the new recipe for success.

Musicians like AP Dhillon, Karan Aujla and before his death, Sidhu Moose Wala, created a new wave of music.

But their songs shy away from the Bhangra songs of old.

Even those attributed to the previous success of Bhangra music such as Jazzy B and Dr Zeus hold their status but very much fly under the radar.

Not to mention, there are more artists and fans exploring and experimenting with their music.

Although this is a positive step in terms of representation and creativity, Bhangra music looks to not hold the same appeal.

For example, emerging British Asian artists lean towards more UK rap, drill or RnB.

Jay Milli, Nayana IZ, Pritt, Asha Gold and Jagga are all impactful and proud of their heritage which they make clear through their music.

Even though this highlights a more expansive music scene, which is important, upcoming musicians aren’t attracted to Bhangra as they once were.

One group to emerge with the same motivations as Bhangra bands is the appropriately named ‘Daytimers’.

South Asian musicians, primarily from the UK form the collective. Their origins are of course inspired by the daytimer parties back in the 90s/00s.

These gatherings were so poignant because they provided a space for British Asians to find new artists and music through daytime clubs.

Most British Asians weren’t allowed to go to parties at night, especially girls. There was a cultural idea that going clubbing meant you had bad morals or were a rebel.

So ‘daytimers’ provided a safe space to party and get back home in time for roti.

Fast forward and the new Daytimers are still trying to empower the diaspora, the same way the parties used to.

However, instead of Bhangra, they showcase a pipeline of talented DJs that spin multiple genres like house, hip hop and Bollywood.

One of their talisman, Yung Singh, even presents Punjabi garage.

So, they’re not purposely distancing themselves from Bhangra music, but highlighting that British Asian people are much more than one genre.

That also resonates with British Asian listeners who revel in jungle, EDM, pop and even jazz concerts/listening parties.

Moreover, whilst Desi nights or ‘Bhangra nights’ are still widespread across the country, DJs are at times confusing audiences.

If they label a performance as ‘Bhangra night’ but play this new pool of talent, they’re promoting modern Punjabi music as Bhangra.

Some may hear the likes of Jasmine Sandlas or Diljit Dosanjh and think Bhangra, but they often have more Americanised thumps and harmonies.

This is of course creative and enjoyable in its own way but it’s not necessarily Bhangra. This also begs the question, do British Asians even know what Bhangra music is anymore?

The General View

In order to grasp the general consensus around British Asians and Bhangra music, DESIblitz spoke to some individuals about their relationship with the genre.

Hardeep Singh, a 30-year-old Birmingham native expressed:

“It’s quite scary to have lived through the peak and decline of Bhangra. We always used to go to school and talk about new tracks we heard. B21 or Jazzy B were my favourites.

“I still listen to Bhangra, it’ll be all the songs of my childhood. To be honest, I even go back to the 80s because I’ll discover new songs that were released before I was born.

“It’s kind of like experiencing it all over again. What’s weird is how authentic the music sounds.

“It’s like the group are in your ears making the song. Now it all sounds too electronic and funky.”

Kiran Kaur, a 29-year-old nurse was also living through a similar period to Hardeep but has a different outlook:

“I know about Dr Zeus, Jazzy B and Rishi Rich and Panjabi MC. Obviously, I’ve heard the main Bhangra tracks when I was at school or at weddings.

“But when I started to grow up, rap was taking over. I saw more black and white artists on my TV and they fitted in with my life at that time.

“I wasn’t really exposed to Bhangra unless I was at a family function. Here and there, I’ll come across some Asian artists but I get bored and then turn on some Drake.”

Elias Kalsi, a 22-year-old student in London agrees with Kiran’s views. It seems as if the environment has had a big impact on music interests:

“I haven’t been around Bhangra at all, to be honest. I just thought all Indian music was Bhangra or Bollywood.”

“Me and my mates listen to hip hop or drill, maybe some house or trap music. Depends on the vibe.

“My taste is something I can bop my head too. The beat needs to go proper in! I like good lyrics as well but if it sounds overcomplicated, I hate that.

“I don’t want to analyse music, I want to enjoy it.”

Another student from London, Reiss Hakh, holds a similar belief:

“My dad blasts Bhangra out in the house, so I have an idea of what it is. But music has changed.

“I actually quite liked Sidhu Moose Wala ’cause his stuff was more hip hop influenced. But I don’t think that’s Bhangra.

“But at parties, we wanna hear hard-hitting stuff and I can’t understand Punjabi anyway so wouldn’t be able to listen properly.

Reiss’ sister, Maya*, added to this:

“To be honest, I listen to more Spanish music than I do Bhangra. I can’t understand that but it’s catchy and different.

“Bhangra music is kind of all the same, isn’t it? You hear a dhol, melodies and a repetitive chorus. Not for me to be honest.”

Although, Coventry-based cousins Jas and Indi Mann show there are still British Asian Bhangra listeners:

“We both and most of our friends still listen to Bhangra songs of old. We’re all in our mid-twenties so weren’t really around when it was at its peak.

“But we kind of owe that to our family. All we heard was Bhangra but the way my dad and uncles spoke about it made us appreciate it.

“It’s the same as the Stormzy, Dave or Adele projects that come out now. Everyone talks about it which makes you want to listen to it. It was the same back then.

“We’ll listen to a range of groups from Heera Group to RDB to Alaap. Throw in some Bally Sagoo as well.

“But, we have to admit that we still get down to English songs just as much.”

Once the epitome of the British Asian experience, it seems quite clear that the diaspora is steering away from Bhangra music.

The difference in music consumption and the impact of other genres have meant Bhangra doesn’t hit British Asians as much.

An important factor in the 80s and 90s was Bhangra music was always performed live or shown at gigs.

It was a way for British Asians to integrate into the community, celebrate their art and build their identity. But things are much smoother in modern times.

Maybe the most critical factor is that Bhangra music was undoubtedly a turning point for South Asian culture in the UK.

But, most of the younger generation aren’t aware of how important this genre was for the society they are living in.

That’s not to say Bhangra listeners aren’t out there – Hardeep, Jas and Indi emphasise that. But, the popularity of Bhangra music is not on the scale it once was.

The shining light? Music, just like fashion is periodic, it can lose its appeal but then make a comeback years later. So, time will tell.

Learn more about the power and full history of Bhangra music here.