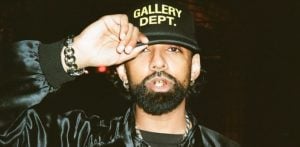

"It’s very relatable, even though the things that we’re talking about might not be relatable to everybody"

Hari Kondabolu’s Netflix comedy special, Warn Your Relatives, marries the insightful social commentary that we’ve come to expect from the Indian American comedian with a more personal touch.

The Brooklyn-based comedian and writer saw his 2017 documentary, The Problem With Apu, cause much controversy. It examines the arguably stereotypical depiction of the immigrant shopkeeper, Apu, in The Simpsons.

While the documentary continues to receive much attention, Hari Kondabolu’s other projects have been equally provoking and entertaining.

With its global release on 8th May 2018 on Netflix, Warn Your Relatives brings the comedian’s clever humour to video for the first time.

Filmed in front of a packed audience in Seattle, Hari Kondabolu entertains with his deft handling of tricky topics including terrorism and mass shootings.

Warn Your Relatives additionally sees the comedian explore family matters, complementing the return of his podcast, The Kondabolu Brothers.

Reflecting on themes from his hilarious podcast with his brother, Ashok Kondabolu, his partner-in-crime is a DJ and member of the music group Das Racist, known as Dapwell.

In the fun and banter-filled podcast, The Kondabolu Brothers travel from city to city in the United States. Their witty rapport entertains all during segments like “Overrated/Underrated?”, giving their personal takes on cultural matters and pop culture.

In an insightful interview, DESIblitz talks to Hari Kondabolu about his perspective on comedy in light of the various aspects of his life.

Whether it’s being a comedian in the age of social media and online streaming, or his South Asian background and his strong familial bonds.

What inspired Warn Your Relatives and how did Netflix come to release it?

I’ve been doing stand-up for quite some time and I’ve wanted to release a video special. I mean, I’ve released albums, but I wanted to release a video special. That was the goal for the year.

So I had been working on a new hour and I felt like it would be good to have that goal. I was planning to do it regardless.

Then we approached Netflix to see if they were interested and they said “absolutely” – which was great to know! Like, you work so hard so it’s great to know that there is that interest. That they do want you to create something for them.

So it was a big deal and it is a big deal.

But in terms of working on it, I toured the US for a good chunk of the year, really getting the jokes right – writing and rewriting.

It’s at least a year’s worth of work, and some of the bits were from earlier too.

So, you’ll go to smaller venues and see what works?

That’s the most important part. Yeah, a lot of it is – I go to Seattle and a small venue there and I just work it out from scratch.

Some of it doesn’t make it or some of it… there’s like a seed of an idea. That’s certainly helped.

In Warn Your Relatives, you have a bit that you play out a few times. So you change the punchline to show how it completely changes the joke?

What’s funny is that whole bit was originally me trying to figure out which one was funniest. Then I realised that the whole joke was the trying to figure it out.

You can only figure out that that is the joke by running it a few times and realising that this is effective. Like people actually like to be a part of the show like that.

You talk about performing for audiences. Do you adapt your comedy for them?

Comedy is very much about adapting.

Because you’re in a different place each time and you don’t know the dynamic, even a room might be different.

Sometimes you’re in a room that might be a little strange, that’s too big or too small or is lit weird or the sound isn’t as good.

If you pretend that none of those things are happening, the audience knows you’re not in the moment, you’re doing a show as you would do anywhere.

So at the bare minimum, adapting to setting and audience is important on that level.

Also, if the show is not going well, everyone knows – so what can you do to break out of that?

Improvisation is such an important tool. You have to be able to, willing to be yourself. As you have to remember, it’s not just the material people like, they like you. They come for you.

It almost doesn’t matter what you say, as long as they see you up there doing comedy. Whether the joke was scripted or not, it doesn’t matter.

In those moments, you have to break the rhythm. You have to make sure they know that you’re with them, you’re on top of them and you’re aware, you’re energised, that’s all part of the job.

If you’re in a city or place that maybe you don’t have the biggest audience and they’re all new to you and you’re new to them, you have to find a way to relate to them.

I’m not going to change who I am. But my goal is to present things in a way where people can understand what I’m talking about.

Even if they don’t completely relate, they least understand, they have enough information to understand – and that’s on me.

In Warn Your Relatives, you talk about meeting Tracy Morgan and knowing that it could become material for your comedy routine. Do you often have these moments?

Oh yeah, I mean that was an easy one, just because it was so absurd.

But you know when things like that happen, there’s certainly a level of gratitude.

Like this is a lot, there’s so many different types of jokes, like stories, things that happened, there’s observations, there’s quick things, like really well-written little pieces, there’s so many different ways to write jokes.

But when the personal experiences happen that are kind of absurd, those are just…they’re gifts, absolute gifts. That was an example of them and yeah, you tend to know.

What are your thoughts on social media, particularly as a comedian?

I think social media is very addictive and you tend to forget that it’s some random person writing an opinion, for better or worse. So you shouldn’t take it too personally but sometimes it’s hard!

Sometimes it’s like you can’t help but read things that you shouldn’t read. And you’re like: “but this is completely wrong!” But it’s like: “yeah they know, they don’t care, they want you to react.”

So there’s that aspect of trolling which is a waste of time.

Sometimes I worry that creatively, does it affect me when I’m writing something for Twitter versus writing something for my act? Because once you put something on Twitter, you forget that you even wrote it -“oh yeah, like that’s out in the world.”

Because instead of the usual, or the way things used to be, where you’d create something and you’d prepare it for a future show, you’re putting it online and want that initial feedback and you forget.

You forget that: “oh yeah this wasn’t just for likes and retweets, this was an original thought.”

Is there a pressure as a comedian to always be ‘on’?

Yeah, to some degree. I know that recently I’ve been promoting different projects a lot and after a while, it’s tiresome.

People want to see something or read something that they can share or that they find entertaining. Otherwise, they could be following somebody else.

They just don’t want constant advertisements, so it forces me to be like: “okay what can I give people today that’s unique and new and valuable?”

Netflix are releasing quite a few shows from Asians like Hasan Minhaj or Aziz Ansari. Do you think the increased popularity of these platforms offers more opportunities to Asians?

Yeah, they definitely give us more options. Part of it is the old days. There was a handful of channels, like cable and everyone was like going for the biggest piece.

Now, because everything is so distributed, there’s so many different platforms, people just want a piece. When you want a piece, you think about things differently.

You’ve not thinking about “what will the majority want to see?” You’ve thinking about: “what will people want to see? What will draw a crowd?”

Maybe, in the past people would have been hesitant to give me a special because I’m doing well, but I’m not at a certain level. Like I’m not Chris Rock and I’m not [Dave] Chappelle.

But I think these platforms, they give you that possibility of “let’s invest in somebody because we do see some long-term with them maintaining an audience.”

Whoa @juniorbachchan was watching my @NetflixIsAJoke special. What’s the verdict, sir? pic.twitter.com/RHJf3BHftz

— Hari Kondabolu (@harikondabolu) May 13, 2018

You talk about how much Asians love mangoes or white people’s reactions to “ethnic food” in general. What are your thoughts on cultural appropriation?

I don’t think eating foods from different places is cultural appropriation. I think the whole thing about ethnic food…like if you call something “ethnic food”, then you probably don’t know too many ethnics.

That’s [the bit] less about cultural appropriation and it’s more about, like, if people are normalised to you, you don’t see it as like this weird outside thing.

Also, everyone has ethnicity – white people have ethnicities! Maybe those ethnicities are suppressed for the sake of being white, but people have them, people have their heritages. The idea of being ethnic is strange.

Let’s say if someone was to open an Indian restaurant and they were white people and, kind of, presenting their own version of things, that might be a little annoying.

But it’s hard with food. Food is always the one that people only care if it’s good, you know what I mean?

I feel that with everything else, like with fashion, art, or music…but with food I feel like people make exceptions because I’m like: “yeah, but this is great.” I think food is tricky with that.

But generally speaking, it’s nice when the people who make a work originally or make something originally, who do the work or are a part of a culture, can actually benefit from their own culture.

Is it important for you to receive good feedback from other South Asians?

Of course, I want my community to be proud of me and to like the work.

But I also know that I can only be myself and maybe there’s things that people disagree with. Maybe there’s ideas that don’t resonate with everyone.

But that’s okay. My job is to do the best job I can and be as funny as I possibly can.

Certainly, I’m aware of the fact – like where I did that mango thing – I’m certainly aware of the fact that there’s going to be a contingent of the audience that is going to be more connected to that. They’re going to appreciate that joke on a different level.

But, I still have to write it so many people as possible like it. So that is the balance.

But at the end of the day, if I can stand behind it and I’m proud of it, it doesn’t really matter what people think.

You discuss how funny your mum is and how she’s always been open-minded about the LGBT community. Is it important to break stereotypes of Asian parents? Especially in comedy?

Oh yeah. Yes. You’re the first person who’s asked me that and that’s absolutely yes, yes.

I mean, I put that in there, not only because that’s who my mum is and because I want people to know her.

But I’m aware that the way that I portray my mum is very different than how other people portray their parents who might be immigrants.

She’s not a caricature, she’s a complete person. She’s funny, she’s thoughtful, she’s clever. Also, she’s not someone who’s frozen in time.

You know, I think about all immigrants. What I hate about these depictions is that all these immigrant seem to be frozen in time and lost in the old country and that.

People adapt very quickly and also, the person who my mother was when she came to this country, isn’t the person she is now. That’s just true with all human beings over time.

It’s hard to put all that complication into a stand-up act. But just to be able to be like: “oh I haven’t heard someone who has immigrant parents talk about these other issues like that.”

I want to make them as multilayered as possible.

And the fact she’s a woman obviously – that’s important too because I think…immigrants are marginalised and I think obviously women are even more so in that group.

So my mum is the most important person in my life and that was my way of making sure that’s clear.

That’s surprising as it’s so important in your show?

I think for that to make sense: one I think the interviewer has to be someone whose parents are immigrants more likely and secondly who are conscious of those things.

I think that’s surprisingly few, but that’s certainly important to me and I like what you said, being knowingly funny – that’s crucial. It’s not that this person is stumbling into something funny because they say things awkwardly or because their accent, they’re funny because they’re funny.

They’re funny because they’re witty and they know what works and what to put together to get a reaction. Like it’s clever stuff.

What made you want to start a podcast and what does it offer you as a comedian?

I mean I love the podcast with my brother and we had a different version of it that was mostly done with poor production values in each other’s homes or in our parents’ basement.

We hadn’t done it in a while and we’d been doing live shows for at least a decade, just not consistently.

But it’s clear that when we’re in a rhythm, we’re very good on stage together. It’s dynamic. People know there’s some structure that I provide and there’s some direction, but it’s loose.

My brother can go in any direction so you can’t really control it – they know it’s going to be improvised, which already I think excites.

Plus it’s a familiar dynamic. Like people, they have close relationships with their siblings, or their cousins, or their parents and there’s something about seeing that, it’s very relatable, even though the things that we’re talking about might not be relatable to everybody. The dynamic is relatable.

But I think people are willing to listen partly because it’s so familiar – even if they don’t understand this complicated back and forth about therapy that my brother and I are having.

They understand the dynamics of older brother/younger brother getting frustrated with each other and being completely different. Comedically, it’s really enjoyable.

Also, it’s made me a better stand up comic – being forced to improvise. He doesn’t make it easy, he’s exactly who he is, which is great.

But it also means that I have to respond in the moment, I can’t be wedded to a way things are done.

It means that often I’m so comfortable that I’m writing on stage, coming up with ideas on stage, because he’s so free.

I think it made me a better performer, without a doubt. I’m very lucky to be able to do that with him.

How was the experience of recording The Kondabolu Brothers with your brother being your brother?

I think there are moments in the podcast where I learn things about him that I didn’t know or vice-versa.

There’s a degree of honesty that we have in public, which strangely, when we’re in private, we don’t always share certain things – which is a really bizarre, uneven dynamic.

But it means that what people are witnessing is very personal and compelling because we’re not holding back, it is really thoughtful.

I discover things as he is discovering things as well, it’s almost like a public therapy session, which I think…I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone really do this.

It’s a really unique format and it’s a really unique set-up and I think that’s the reason why the people who do listen to it, get obsessed with it – because it’s so unique and it’s so different and there’s nothing like it.

DESIblitz couldn’t agree more. Both Hari Kondabolu’s Netflix special Warn Your Relatives and podcast feel incredibly fresh, funny and relatable.

Instead of furthering the same stereotypes of South Asians, he eschews these conventional jokes for original takes on South Asians and cultural topics.

He has a talent for finding humour in the terrible, the ordinary and in the act of comedy itself.

Here, the writer and comedian demonstrates how other South Asian comedians can decide their own path in comedy, especially with changes in how we view entertainment.

Warn your relatives, your friends, everyone – Hari Kondabolu’s star will continue to rise during 2018 and beyond.