In her poem, Imtiaz Dharker focuses on the confusion about one’s own identity.

Desi poetry reveals the effects of the immigration on the South Asians. Therefore, we explore five poems on immigration in particular.

Immigration affects each individual differently, but globally each immigrant has similar struggles. Learning a new language and forming a new identity is never an easy process.

The following poems highlight the struggles that all the immigrants go through.

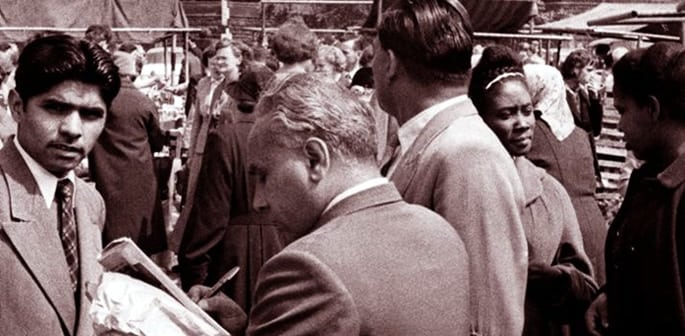

Striking Women reports that South Asians immigrated to the UK and US after 1947 for various reasons.

Some of them immigrated to live with their families who were already there. Others escaped war or for better economic and educational circumstances.

Immigrants who were born in a foreign country are often in limbo where they feel as if they don’t belong anywhere.

People in their homelands often idealise the Western culture. However, the life of those that migrate is often very different.

The disingenuous population of the home country don’t see immigrants as one of their own and people born in the foreign country find it hard to understand their roots and heritage.

Some emotional inner experiences of immigrants closely overlap. The sadness, longing, and alienation of immigrants are expressed in these poems on immigration.

Minority by Imtiaz Dharker

I was born a foreigner.

I carried on from there

to become a foreigner everywhere

I went, even in the place

planted with my relatives,

six-foot tubers sprouting roots,

their fingers and faces pushing up

new shoots of maize and sugar cane.

All kinds of places and groups

of people who have an admirable

history would, almost certainly,

distance themselves from me.

I don’t fit,

like a clumsily-translated poem;

like food cooked in milk of coconut

where you expected ghee or cream,

the unexpected aftertaste

of cardamom or neem.

There’s always that point where

the language flips

into an unfamiliar taste;

where words tumble over

a cunning tripwire on the tongue;

where the frame slips,

the reception of an image

not quite tuned, ghost-outlined,

that signals, in their midst,

an alien.

And so I scratch, scratch

through the night, at this

growing scab on black on white.

Everyone has the right

to infiltrate a piece of paper.

A page doesn’t fight back.

And, who knows, these lines

may scratch their way

into your head –

through all the chatter of community,

family, clattering spoons,

children being fed –

immigrate into your bed,

squat in your home,

and in a corner, eat your bread,

until, one day, you meet

the stranger sidling down your street,

realise you know the face

simplified to bone,

look into its outcast eyes

and recognise it as your own.

Imtiaz Dharker was born in Lahore in Pakistan. She moved to Scotland, Glasgow as a little girl.

In her poem The Minority, Imtiaz Dharker reveals the confusion about her own identity as an immigrant.

She expresses the feeling of displacement which comes from being a foreigner. Imtiaz is foreign where she was born and in her own country.

The personification of language expresses the inner division of identity. Because of it, the foreigners see the world around them differently.

The taste of our own tongue becomes unfamiliar even to us. The remaining taste is the one of non-affiliation.

People who are not immigrants can’t relate to the immigrant experience which brings loneliness and alienation to the immigrants.

The imagery of sugarcanes, maze, and children reveals the author’s nostalgia. Imtiaz Dharker deeply longs for the landscapes of Punjab in Pakistan.

The end of the poem brings some consolation because any stranger on the street could understand our pain.

Poems on immigration like this one help us miss our homeland in the safe arms of Imtiaz Dharker’s empathy and comfort.

The Immigrant’s Song by Tishani Doshi

Let us not speak of those days

when coffee beans filled the morning

with hope, when our mothers’ headscarves

hung like white flags on washing lines.

Let us not speak of the long arms of sky

that used to cradle us at dusk.

And the baobabs—let us not trace

the shape of their leaves in our dreams,

or yearn for the noise of those nameless birds

that sang and died in the church’s eaves.

Let us not speak of men,

stolen from their beds at night.

Let us not say the word

disappeared.

Let us not remember the first smell of rain.

Instead, let us speak of our lives now—

the gates and bridges and stores.

And when we break bread

in cafés and at kitchen tables

with our new brothers,

let us not burden them with stories

of war or abandonment.

Let us not name our old friends

who are unravelling like fairy tales

in the forests of the dead.

Naming them will not bring them back.

Let us stay here, and wait for the future

to arrive, for grandchildren to speak

in forked tongues about the country

we once came from.

Tell us about it, they might ask.

And you might consider telling them

of the sky and the coffee beans,

the small white houses and dusty streets.

You might set your memory afloat

like a paper boat down a river.

You might pray that the paper

whispers your story to the water,

that the water sings it to the trees,

that the trees howl and howl

it to the leaves. If you keep still

and do not speak, you might hear

your whole life fill the world

until the wind is the only word.

Tishani Doshi was born in Madras (Chennai), India and graduated in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. She then moved back to India.

Her work has been published in India, US, UK and The Caribbean.

In this poem, Tishani connects the chain of her childhood memories to her present life.

It begins with the memories of the mornings, skies and mother’s headscarves. Those memories transform into the sight of the metropolitan ”gates and bridges and stores”.

The imagery engaging the sensory detail speaks to the nostalgia of Tishani’s homeland.

Coffee beans engage the sense of smell. The touch of breaking bread brings us back into her homeland.

At the beginning of the poem, Tishani Doshi denies the passage of time and memories by repeating ”Let us not speak of…”. However, she concludes the poem in a positive tone.

There is a hope that our memories will be passed down to others. Our memories are like an echo to our existence.

On Immigration by Prageeta Sharma

After being humiliated one continues the manuscript of identity.

Activities, diseases, doldrums, the crony affair after the situation,

the one where one faces how one is the undertaste,

how one isn’t the neighbor, the piebaker, a white folk. How one isn’t a gorgeous

dream wrapped up in tireless affection, primped for wider screens.

So there one grew, in the coffee sickness, the dictionary browsing

in a fury for the word entitlement to spill—

After convulsing with rage, one continues in the aftermath

of no friends on Tuesdays or shouting fiercely when nothing sobered

to the eleventh hour and the tide shrunk to its sense of privacy where it

had nothing to do with shores or moons, and humiliation sat on its lover’s

knee, greeting the eccentric rich and the hourglass with such force

the rage enameled like fine paint to a sheen of deep blue.

Restless in the way that stirs the crowd to its feet to claim the encounter

for the intentions of personal gain without the empire, without the

embarrassment of shaking one’s head, of resting it underneath the ground, to live sanctioned in the

migrancy with an ugly plate for the economy but working ever

so hard. So unplanned, so beyond what one did before the lack of dignity sang an opera. And

organized all the ideas, before rage shot a bird that had once watched effortlessly all the comings

and goings.

Prageeta Sharma‘s parents emigrated from India to Framingham, Massachusetts, USA, where she was born.

In this poem, she expresses her dissatisfactions with life in America.

The poem ”On Immigration” talks about how not everything goes as planned. Moving to a more developed country doesn’t promise success.

A prose style perfectly conveys the frustration and entrapment.

The consumerist routine of American achievement oriented nation swallows the immigrants.

The striving for sameness and routine doesn’t tolerate anomalies. There is not much compassion for the immigrants in a country where everyone has to conform to the norm.

Not fulfilling one’s dreams forces an immigrant to join the routine. The problem is that he doesn’t feel like he belongs there.

A bird representing dreams eventually dies under the pressures of working life and dissatisfaction with oneself.

Immigrant by Tabish Khair

It hurts to walk on new legs:

The curse of consonants, the wobble of vowels.

And you for whom I gave up a kingdom

Can never love that thing I was.

When you look into my past

You see

Only

Weeds and scales.

Once I had a voice.

Now I have legs.

Sometimes I wonder

Was it fair trade?

(Based on H. C. Andersen’s ‘The Little Mermaid’)

This poem is from Tabish Khair’s first collection Man of Glass.

Short words and wide spaces between stanzas depict the emptiness. Tabish Khair’s discomfort and longing for one’s home country is obvious.

He will never be accepted and loved in his new country. The realisation that he cannot replace or relive how he felt in his home country is extremely upsetting.

Tabish Khair regrets and questions his immigration in this poem.

Tabish admits that it is painful to start again in a new country because it means rebuilding and adapting oneself. It also includes learning a new language unfamiliar to his tongue and jaws.

On his website, Tabish reveals that he worked jobs like dishwashing and house painting when he immigrated to Denmark from India.

Last two strophes have a reference to the ‘The Little Mermaid’. His new legs are a metaphor for transformation into a working-class man. Unfortunately, his voice and individuality got lost in the process.

Trailing Clouds of Glory by Vijay Seshadri

Even though I’m an immigrant,

the angel with the flaming sword seems fine with me.

He unhooks the velvet rope. He ushers me into the club.

Some activity in the mosh pit, a banquet here, a panhandler there,

a gray curtain drawn down over the infinitely curving lunette,

Jupiter in its crescent phase, huge,

a vista of a waterfall, with a rainbow in the spray,

a few desultory orgies, a billboard

of the snub-nosed electric car of the future—

the inside is exactly the same as the outside,

down to the m.c. in the yellow spats.

So why the angel with the flaming sword

bringing in the sheep and waving away the goats,

and the men with the binoculars,

elbows resting on the roll bars of jeeps,

peering into the desert? There is a border,

but it is not fixed, it wavers, it shimmies, it rises

and plunges into the unimaginable seventh dimension

before erupting in a field of Dakota corn. On the F train

to Manhattan yesterday, I sat across

from a family threesome Guatemalan by the look of them—

delicate and archaic and Mayan—

and obviously undocumented to the bone.

They didn’t seem anxious. The mother was

laughing and squabbling with the daughter

over a knockoff smart phone on which they were playing a

video game together. The boy, maybe three,

disdained their ruckus. I recognized the scowl on his face,

the retrospective, maskless rage of inception.

He looked just like my son when my son came out of his mother

after thirty hours of labor—the head squashed,

the lips swollen, the skin empurpled and hideous

with blood and afterbirth. Out of the inflamed tunnel

and into the cold room of harsh sounds.

He looked right at me with his bleared eyes.

He had a voice like Richard Burton’s.

He had an impressive command of the major English texts.

I will do such things, what they are yet I know not,

but they shall be the terrors of the earth, he said.

The child, he said, is father of the man.

This poem was written in 1954.

However, the immigrant experience depicted here is similar to the modern poems. It reflects the alienation and loneliness of the immigrants.

Vijay Seshadri personal references make this poem deeply intimate.

The birth of the author’s son made a strong impact on him. Vijay Seshadri also refers to the angel and his religion.

Religion, birth, and the immigration hold the element of unpredictability and fear. The poet shares the introspections of his new beginning as an immigrant.

Vijay Seshadri is possibly speaking about his own experience.

As a little boy of five, he moved from India to the US in Columbus, Ohio. He projects it on the little boy on the train to Manhattan. A confused and enraged boy represents the author’s feelings during his immigration.

The poem seems like an author’s intuition and his inner voice. He is observing his life from the outside. This gives the multi-dimensional meaning to the immigration.

Reading these poems on immigration in tough moments can help us heal. Poetry can raise the awareness of the of the immigrant’s hardships.

To the immigrants, they can give solace. To those aren’t immigrants they give a peek into someone else’s personal experience.

In the sea of fear, poetry can be a drop of safety. Each stanza is a moment of visiting our home. In poetry, we have a safe space to revisit our homeland in memories.