"it always ends up in family WhatsApp groups."

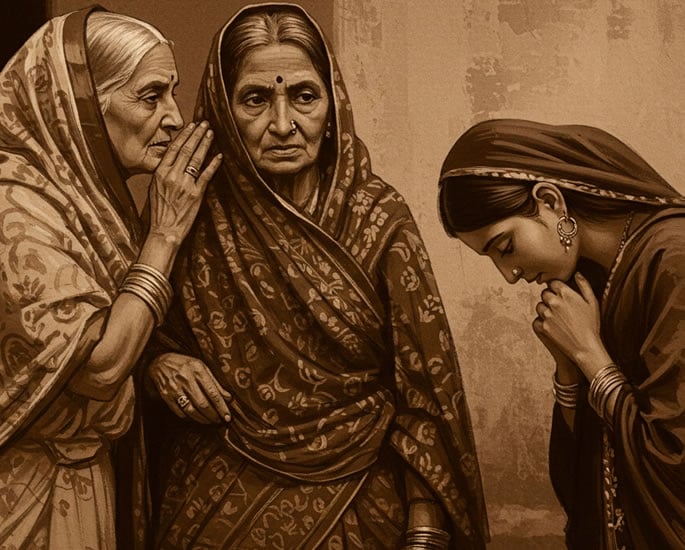

‘Aunty culture’ has long been a defining factor within South Asian communities.

It is a system where older women, often positioned as guardians of morality, use gossip and judgment to regulate behaviour and enforce conformity.

It begins in a familiar place, a living room filled with steaming cups of chai, where a bride’s outfit is dissected, a neighbour’s son is mocked for not finding a “proper” job, and a daughter is whispered about for being seen with a boy after dark.

At first glance, these conversations seem harmless, even amusing. But beneath the surface, aunty culture functions as a mechanism of control, sustaining patriarchal norms, punishing non-conformity, and shaping reputations that extend far beyond the living room.

The ‘aunty’ figure embodies a culture of surveillance that dictates social boundaries, particularly for women and youth.

DESIblitz explores how aunty culture developed, how it continues to operate today, and what it means for identity, autonomy, and cultural change.

The Historical Roots of the Aunty Figure

The aunty as a cultural force did not emerge overnight.

In pre-colonial South Asia, collectivist societies placed strong emphasis on family honour and community reputation. These unwritten codes often carried more weight than formal law.

British colonial rule reinforced these systems by introducing Victorian ideals of respectability, domesticity, and rigid gender roles.

Men were increasingly linked to education and earning, while women were confined to domestic spaces, judged by modesty and obedience.

These ideals seeped into households.

A “good woman” was expected to be silent, family-oriented, and self-sacrificing while a “good man” was ambitious and public-facing. Families absorbed these standards, where deviation brought shame not just to individuals but to entire lineages.

Samina Khan* explained: “It wasn’t just my parents I worried about.

“It was the aunties at weddings, always commenting on my clothes or who I spoke to. Their words carried weight.”

Women became responsible for safeguarding family reputation, monitoring both their behaviour and that of others.

Over time, this duty became a form of authority.

The aunty emerged as both feared and respected, her disapproval enough to stain a family’s social standing.

Global Social Policing

At the heart of aunty culture lies gossip. Unlike casual storytelling, gossip here functions as a system of surveillance, ensuring that everyone knows they are being observed and judged.

For young women, seemingly small actions become scandalous.

A girl holding hands with her boyfriend may see her reputation ruined before her parents even hear about it. For young men, choosing art over medicine can trigger endless comparisons with “successful” cousins.

Even private choices, like remaining unmarried, are recast as selfishness or misfortune.

Gossip turns personal lives into public commentary, shaping reputations through whispers more powerful than rules.

What makes this system effective is its reach. Shame flows not only from elders but from cousins, friends, and peers, ensuring the surveillance is constant and unavoidable.

In diaspora communities, gossip extends across borders. A photo posted in London can reach Lahore within minutes, sparking conversations in family WhatsApp groups.

This is the case for 24-year-old Sana Rahman, who said:

“I avoid posting anything personal on Instagram because it always ends up in family WhatsApp groups.

“By the time I hear about it, the aunties have already judged me.”

Why Women Bear the Burden

Although aunty culture can target anyone, women disproportionately carry the weight of its judgments.

Their clothing, relationships, and career choices are far more scrutinised than those of men.

This imbalance is rooted in history, as women have long been positioned as carriers of family honour.

From pre-colonial norms to Victorian morality, women were seen as symbols of virtue.

Men could often recover from mistakes, but women’s reputations were fragile and tied directly to family pride.

Patriarchy compounds this divide. Women are tasked with upholding respectability while being judged by it themselves. Their authority often depends on reinforcing the very standards that limit their freedom.

Aisha Khan told DESIblitz: “At weddings I feel like I’m on display.

“Aunties comment on my weight, clothes, or why I’m not married. I laugh it off, but inside, it makes me question myself.”

This dynamic reveals the paradox of aunty culture: women become both enforcers and victims, internalising control while disguising it as care.

Aunty Culture in Media and Pop Culture

Bollywood and South Asian television have played a central role in normalising the stereotype of the judgmental aunty.

From the nosy neighbour in soaps to gossipmongers in comedies, the figure is often ridiculed yet legitimised.

Films such as Dil Dhadakne Do highlight how women’s choices become the subject of social commentary.

Ayesha (Priyanka Chopra) has a successful business but is in an unhappy marriage. When she talks about possibly leaving her husband, her mother says walking away from a marriage is cowardly and instead of chasing her career, Ayesha should focus on her family life.

Similarly, family dramas like Hum Aapke Hain Koun..! portray extended relatives constantly inserting themselves into personal matters.

From matchmaking conversations to overseeing wedding rituals, relatives are depicted as ever-present decision-makers.

Their involvement is framed as love and duty, but it reinforces the idea that surveillance is a natural part of family life.

Television serials continue this pattern. Older women are regularly portrayed as moral guardians and their authority is rarely challenged.

Hamza* said: “You see these aunties on screen and laugh, but the message is clear; they’re powerful, and what they say matters.”

The normalisation of this authority means audiences absorb the idea that community policing is inevitable.

On social media, “aunty memes” provide humour and sometimes resistance. Yet this humour has limits.

Priya* explained: “I laugh at aunty memes online, but when relatives comment on my photos or tell me I’m not ‘modest’ enough, it stops being funny.”

The digital space offers satire, but it also magnifies scrutiny.

The Human Cost

The strain produces cycles of anxiety and burnout.

Fear of gossip in weddings, online, or everyday spaces becomes background noise that shapes daily life.

Sahaj Kaur Kohli, the founder of Brown Girl Therapy, reflects on her early therapy experiences:

“Therapy was the first time I had a professional, confidential space to talk about myself and my feelings without worrying if I was taking up too much space… that created the permission to break the idea that I should always live for others.”

Aunty culture extends beyond casual chatter; it forms a psychological system that shapes identity and

mental well-being across generations.

How Younger Generations are Pushing Back

Despite its persistence, aunty culture is being challenged.

Younger generations, particularly in the diaspora, are creating new ways to resist.

Therapy is one avenue. Platforms like South Asian Therapists connect individuals with counsellors who understand these cultural pressures, offering tools to reclaim autonomy.

Creativity has also become resistance. Podcasts such as The Desi Condition and writers like Nikesh Shukla create space for taboo conversations, giving voice to experiences once silenced.

Social media amplifies these efforts. Campaigns like #BrownGirlJoy and #DesiFeminism encourage self-expression, reframing pride where shame once stood.

These shifts reveal a refusal to conflate honour with silence, or tradition with control. For many young South Asians, self-expression is not rebellion but survival.

Rethinking Honour and Respect

Researchers have argued that there needs to be a clearer distinction between shame and honour.

True honour, they suggest, is rooted in empathy and dignity rather than surveillance or control.

Moving forward, intergenerational dialogue is often cited as key.

A 2022 study found that structured conversations between parents and children around autonomy reduced conflict and strengthened trust.

Programmes like community workshops in Leicester and Birmingham have trialled this model, encouraging families to discuss topics such as marriage and education openly rather than through silence.

Religious and educational institutions are also beginning to adapt. Some gurdwaras and mosques in the UK have introduced youth forums that allow younger members to raise concerns without fear of judgment.

These initiatives provide an alternative to traditional spaces, where dissent is often dismissed as disrespect.

Grassroots organisations are taking the lead.

Platforms like South Asian Therapists connect communities to culturally sensitive counselling, while publications such as Brown Girl Magazine amplify younger voices pushing against restrictive norms. Their work demonstrates that culture can evolve without being rejected outright.

Shaista Aziz Patel, Assistant Professor at UC San Diego, argues in her work on gender and coloniality that rethinking honour is not about discarding tradition but recognising that traditions themselves have always changed.

This perspective highlights how cultural values can adapt to support individuality while retaining collective identity.

Aunty culture thrives on gossip, but its power endures through silence. By naming it and offering alternatives, South Asians can begin moving beyond its influence.

This is not about rejecting culture or mocking elders. It is about rethinking traditions so they uplift rather than restrict, and ensuring that respect does not come at the cost of individuality.

As younger generations continue to challenge outdated norms, they show that cultural evolution is both

possible and necessary.

The future of South Asian communities will not be defined by surveillance and shame, but by authenticity lived within culture rather than against it.