they focus on “the institution of marriage"

Jane Austen’s novels have long travelled beyond the quiet drawing rooms of Hampshire, finding a remarkable resonance across South Asia.

Indian cinema, in particular, has repeatedly adapted Austen’s narratives, demonstrating that the author’s exploration of marriage, reputation, and social hierarchy is not confined to early 19th-century England.

Her works continue to captivate audiences because they reflect realities that remain visible in contemporary life, showing how interpersonal negotiations, moral growth, and social perception operate across cultures.

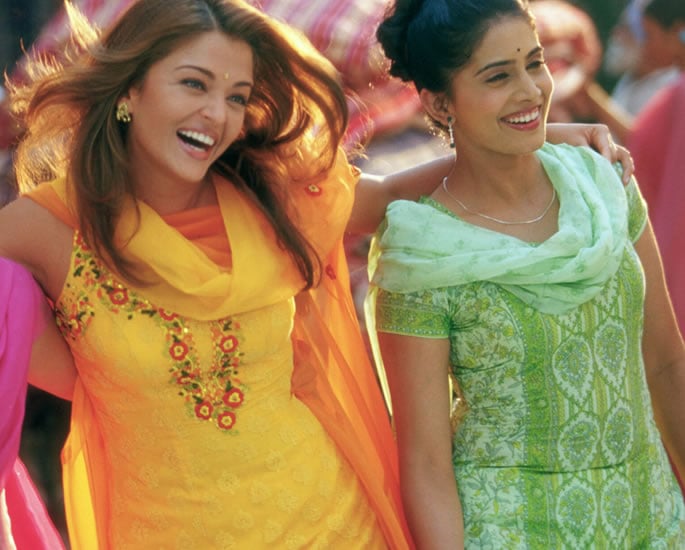

From Bollywood films to British Asian adaptations, Austen’s stories are continuously translated and reimagined, confirming that her understanding of human behaviour transcends geography.

This enduring appeal raises a question: what is it about Austen’s world that makes her such a natural fit for South Asian storytelling?

Matrimonial Stories

At the heart of Jane Austen’s narratives lies marriage, treated not simply as romance but as a complex social and economic negotiation, one observed closely by family and community alike.

Scholars Shibani Das and Gautam Sarma explain that her novels endure because they focus on “the institution of marriage, the urge to rise the social and economic hierarchy, and the fragile web of life that interconnects all the family members”.

This is a dynamic that resonates with Indian audiences who inhabit similar social structures.

Films such as Gurinder Chadha’s Bride and Prejudice succeed because they capture this pressure authentically.

As Das and Sarma observe, the movie “wonderfully succeeds in showing how the cultured society of Indian origin treats a lady who is considered to be of age to get married and the tensions haunting the parents of the Indian household”.

The humour works precisely because the social anxiety it portrays is instantly recognisable.

Status

Jane Austen was meticulous in mapping social hierarchies, showing how wealth, birth, manners, and education subtly determine standing and influence.

Indian society, with its intricate systems of caste, community, and conspicuous consumption, recognises the same patterns of judgement and expectation.

Bride and Prejudice reinforces these parallels while adding a postcolonial dimension, as Das and Sarma note, highlighting “preconceived notions of the native Indian land, people, values, and cultures”.

In both contexts, individuals navigate constant evaluation, whether it is the critical glance of a Lady Catherine de Bourgh or the assessing eye of a non-resident Indian mother scrutinising a potential daughter-in-law.

This shared awareness of status allows Austen’s observations to feel relevant, precise, and remarkably contemporary.

Agency within the Drawing Room

While Austen’s heroines often operate under strict constraints, their intelligence and moral insight allow them to exercise agency in subtle but decisive ways.

Elizabeth Bennet’s refusal of a financially advantageous marriage is a radical act of self-possession within a society designed to limit her choices.

Indian adaptations echo this tension clearly, presenting characters like Lalita Bakshi or Aisha Kapoor in Rajshree Ojha’s Aisha, who negotiate expectation while maintaining autonomy.

Das and Sarma describe “the pressure of finding a suitable suitor for marriage and getting married at the earliest”, a tension that these heroines navigate with intelligence and subtle resistance.

In both Austen’s and Indian contexts, modernity or material comfort does not eliminate social pressure, and the journey toward moral and emotional clarity becomes the central narrative arc.

Importance of Reputation

Reputation operates as a central force in Austen’s works, where misunderstandings, gossip, and social scrutiny drive plot and character development.

This dynamic is equally powerful in Indian contexts, where social circles, community networks, and familial expectations ensure that private actions quickly become public concerns.

Zoya Akhtar’s Dil Dhadakne Do exemplifies this phenomenon.

This shows how fear of social judgment can outweigh personal happiness.

Das and Sarma emphasise that both Jane Austen’s novels and their adaptations foreground “misconception and misunderstanding among the varying characters”.

This proves that the machinery of social evaluation is both universal and timeless, governing choices in ways that extend far beyond geographic boundaries.

Education of the Heart

Beyond marriage and reputation, Austen’s novels are fundamentally moral journeys, focused on the cultivation of insight, humility, and ethical awareness.

Characters must confront pride, prejudice, and self-deception before achieving personal growth or romantic resolution.

Indian adaptations retain this structure faithfully, preserving the trajectory from error to understanding even as cultural contexts shift.

Das and Sarma note that while the settings may change, adaptations remain “similar in terms of their intertwining plot and storyline”, particularly in emphasising character reformation.

It is this moral architecture, rather than romantic spectacle alone, that ensures Austen’s work remains compelling across time and place, offering lessons that resonate equally with audiences in South Asia.

Jane Austen’s enduring popularity in South Asia stems from her acute observation of social systems and human behaviour rather than nostalgia or literary heritage.

Her insight into marriage, status, reputation, and moral development aligns seamlessly with cultural realities that continue to shape Indian life.

Onscreen adaptations demonstrate that her narratives are not simply portable, but remarkably adaptable, reflecting familiar pressures and ethical dilemmas with precision and clarity.

From the drawing rooms of Longbourn to the ballrooms of Bollywood, Austen’s work continues to feel not just relevant but intimately connected to the world she never visited, confirming her place as a universally perceptive social chronicler.