Under Jahangir, flowers were often presented in isolation.

Flowers are woven throughout Mughal art, blooming in painted borders, carved marble surfaces, and the luxurious textiles of the imperial court.

Their forms remain recognisable across different periods, reflecting a sustained attentiveness to plants and nature within both artistic and courtly life.

Floral imagery existed in earlier South Asian traditions, but the Mughals developed a distinct visual language, shifting between botanical precision and artistic interpretation.

These motifs did not remain fixed; they travelled between paintings, architecture, textiles, and smaller objects, subtly reshaping their meaning with each transition.

Floral decoration also linked the Mughals to Persian aesthetics and the Timurid legacy of Central Asia.

Tracing the rise of floral imagery in Mughal art therefore reveals how artistic traditions across Asia intersected, adapted, and evolved across materials and contexts.

Early Roots

Many elements of Mughal floral imagery can be traced to Persian art.

In Persian manuscripts, floral borders framed poems and narrative scenes, enclosing text and image within carefully ordered designs.

These borders were not decorative afterthoughts but part of a recognised visual system. Their regular appearance made them almost expected within particular manuscript traditions.

As illustrated manuscripts circulated through Central Asian courts, the floral motifs that adorned them travelled too.

Over time, they shaped the visual world in which Babur, the Mughal emperor, was raised.

When Babur entered the Indian subcontinent in the early 16th century, he carried this visual inheritance with him. He also brought a personal fascination with gardens and plants, frequently noting flowers in his memoirs, often commenting on colour or scent.

These observations were sometimes informal, as if recorded for private reflection rather than public record. Yet this habit of close looking likely shaped the early Mughal approach to representing nature.

During Akbar’s reign in the late 16th century, the Mughal atelier began blending inherited methods with new experiences.

Artists encountered plant life unfamiliar to those from Central Asia and started recording these new forms. Even so, floral imagery remained secondary, appearing mainly in borders, architectural details, or small decorative spaces.

Gardens occupied a central place in imperial culture. The charbagh, a symmetrically divided garden organised into four sections by water channels, symbolised harmony and order.

Flowers were essential to these spaces, marking seasonal shifts, enriching colour and scent, and shaping the sensory atmosphere.

Their symbolic presence laid the foundation for a broader use of floral imagery in Mughal art.

As the empire expanded, new influences entered the imperial workshop. Persian book arts, Indian architectural decoration, and the subcontinent’s natural environment began to intersect.

With these traditions meeting, the conditions emerged for a deeper focus on floral subjects. What remained was the arrival of a ruler who encouraged an even closer study of nature.

Jahangir’s Era of Naturalism

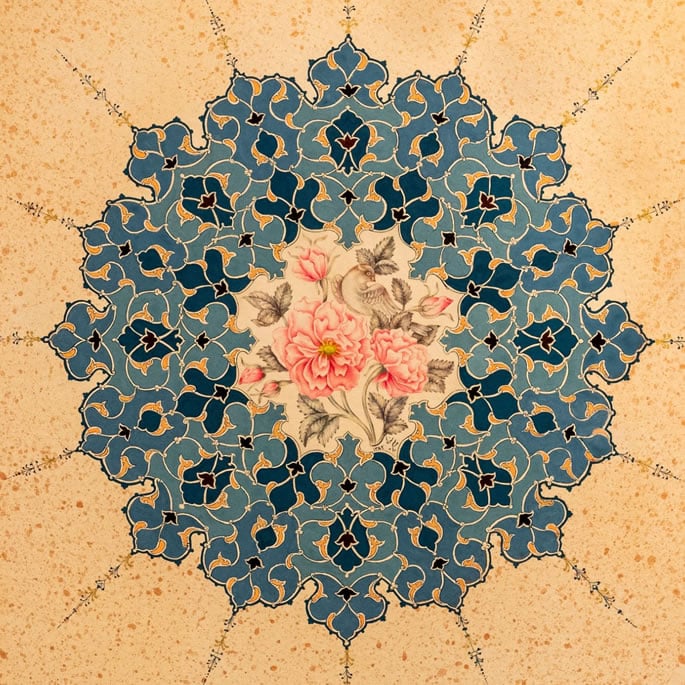

Mughal Emperor Jahangir oversaw the shift from imaginative floral motifs to imagery grounded in realism and specificity.

His interest in natural history is well documented, including collections of unusual plants and animals accompanied by detailed notes and commentary.

He insisted that artists depict these specimens accurately, encouraging painters to study individual plants closely rather than relying on inherited conventions.

Under Jahangir, flowers were often presented in isolation. Instead of being embedded within complex scenes, they were placed against plain backgrounds.

This approach removed visual distractions and made the structure of each plant easier to observe. The resulting images carry a calm, measured quality.

European botanical engravings reached the Mughal court through expanding trade networks. Artists studied them and experimented with similar techniques, including graduated shading and more consistent spatial organisation.

These ideas did not displace existing miniature traditions. Instead, they operated alongside them, producing a cumulative style shaped by multiple visual systems.

Ustad Mansur, one of the most celebrated painters of Jahangir’s court, became especially associated with naturalistic flower studies during this period. Although only a portion of his work survives, the remaining examples reveal careful observation and exceptional detail.

His approach influenced the direction of Mughal painting, particularly in its treatment of botanical subjects. This growing emphasis on natural study altered the role of floral imagery.

Flowers moved beyond decoration to become subjects in their own right, reflecting the court’s sustained curiosity and desire for a deeper understanding of the natural world.

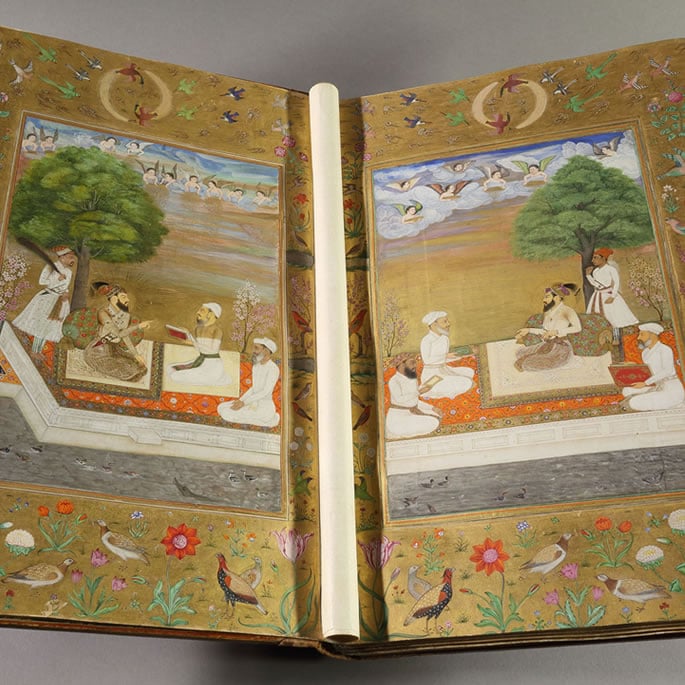

Flowers in the Album Tradition

While naturalistic studies developed under Jahangir, floral imagery also expanded through the album tradition.

The imperial album, or muraqqa, brought together paintings, drawings, and calligraphy in a format intended for close, intimate viewing. Its margins gave painters space to test new ideas or revisit familiar motifs in subtly altered forms.

By the 17th century, many album pages featured floral borders. These varied widely, with some rendered in careful detail and others adopting a more idealised and stylised approach.

Albums frequently placed different floral styles side by side. This contrast was not treated as disorder but as a deliberate reflection of both nature’s variety and the diverse influences shaping Mughal artists.

Certain flowers appeared again and again. Poppies were often shown with gently bent stems, while irises and lilies introduced a more upright, structured presence.

These albums preserved floral imagery more consistently than many other art forms because they were highly valued objects.

As a result, they became lasting records of the court’s shifting interests in plants, ornament, and visual experimentation.

Many albums later entered European collections, where they played a role in shaping early interpretations of Mughal aesthetics.

The Various Uses of Floral Art

Floral imagery did not remain confined to manuscript pages for long. It moved into other materials, sometimes in expected ways and sometimes through more experimental applications.

Architecture offers one of the clearest examples. Buildings from Shah Jahan’s reign, most notably the Taj Mahal, feature precisely cut pieces of semi-precious stone arranged into floral forms and set into marble surfaces.

These designs were primarily decorative, yet they often carried layered meanings shaped by context. In funerary settings, for instance, floral imagery was commonly associated with ideas of paradise and continuity.

Textiles reveal a different engagement with floral form. Court workshops produced a wide range of fabrics, each adapting the motif in distinct ways.

Brocades incorporated repeating floral patterns woven directly into the cloth.

Embroidered garments used looser interpretations, sometimes simplifying forms until they became deliberately ambiguous. Printed cottons relied on stylised blossoms repeated across expansive surfaces.

Through trade, these textiles travelled far beyond the Mughal empire. As they circulated, some floral patterns lost their original meanings, even as their visual appeal endured.

Carpets offered yet another interpretation, presenting imagined garden layouts with floral forms woven into rhythmic patterns and symmetrical structures.

The motif also extended into metalwork. Floral engravings appeared on objects ranging from mirrors to ceremonial sword hilts and ritual basins.

Each medium demanded its own adjustments, producing forms that were related but never identical. Across materials, floral imagery remained a constant presence.

This adaptability allowed the floral motif to align with courtly taste across generations.

Its ability to move between objects, materials, and meanings explains why floral art became one of the most enduring visual signatures of the Mughal empire.

Meanings and Global Legacy

Understanding the meaning of flowers in Mughal art is challenging because the motif never carried a single, fixed interpretation.

In some works, flowers functioned as points of visual balance, helping to link different parts of a design. In others, particularly in architecture, they suggested associations with the afterlife.

At times, floral motifs appear to have been included simply because they were familiar to artists or widely appreciated at court.

This range of uses makes it difficult to place the motif within a single category.

Multiple artistic traditions shaped the Mughal engagement with flowers, and they did so in ways that did not always align.

Persian garden imagery introduced one set of visual expectations, while local Indian plants brought their own forms and associations. European prints added new ways of describing botanical structure.

When these influences appeared together, they did not merge into a single, unified approach. Instead, they remained partly distinct.

Although Persian symmetry, Indian attention to floral form, and European shading techniques often coexisted, there was no single method for combining them.

Artists could distinguish between these traditions, drawing on each to varying degrees depending on the needs of a particular project.

These floral designs continue to resurface, appearing in exhibitions, contemporary textiles, and artworks that reference different moments of the Mughal past.

The motif proved capable of moving between different settings without losing its essential character.

Mughal floral art was never confined to a single medium, meaning, or style. It circulated across manuscripts, architecture, textiles, and portable objects.

Its development drew on inherited Persian and South Asian traditions, evolving methods of observation and botanical study, and the specific tastes of the Mughal court.

More than simple embellishment, flowers offered artists a direct way to express curiosity about the natural world while retaining creative flexibility.

Taken together, these factors explain why floral imagery emerged as the most defining visual feature of Mughal art.