"Imperialism was about stripping the colonised of all agency."

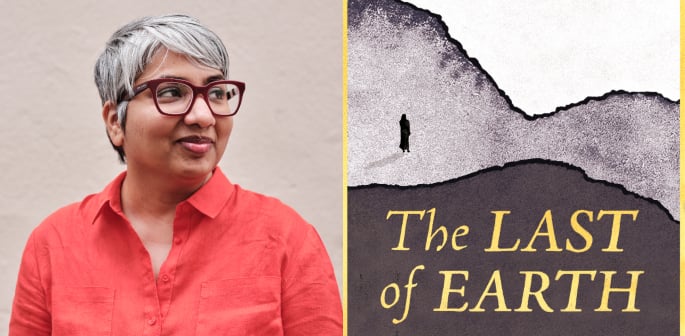

Deepa Anappara’s The Last of Earth is a powerful reimagining of colonial narratives that places Indian voices back at the centre of empire.

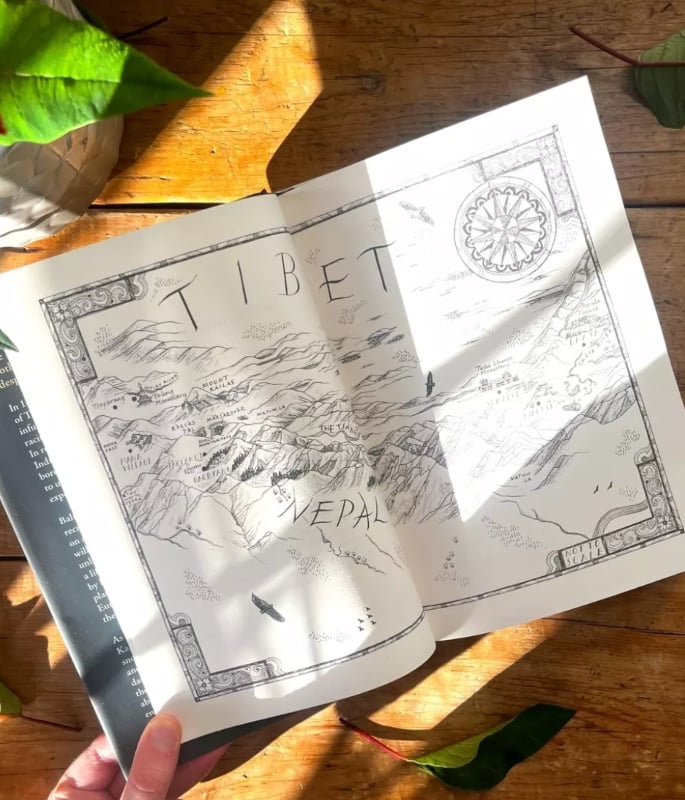

Set against the sweeping landscapes of Tibet and British India, the story follows Balram, an Indian surveyor, and Katherine, a British explorer, navigating fragile privilege.

Through cartography, travel and quiet resistance, Anappara interrogates who gets remembered in history and who is written out entirely.

For British South Asian readers, the novel feels especially resonant, challenging inherited colonial perspectives while reconnecting us with erased ancestral experiences.

Speaking to DESIblitz, Anappara discusses forgotten Indian explorers, imperial power, solitude in extreme landscapes and why fiction can reclaim stories that archives refuse to hold.

The Last of Earth centres Indian voices often erased from imperial history. Why was it important for you to reclaim these hidden stories through fiction?

I was curious about what the Indian experience might have been in the 19th century, when the subcontinent was under British rule.

When I moved to the UK from India over 18 years ago, I was surprised by the extent of ignorance – wilful or otherwise – about the damage caused by colonialism, and it is fair to say that this is what got me thinking about the curated archives that Britain holds about its colonial past.

What are the stories not told in these archives, which try to portray colonialism as a civilising mission?

Fiction allowed me to reimagine those stories.

Balram is inspired by real Indian explorers who were largely absent from archives. How did you balance historical research with imagination when shaping his voice?

In the 19th century, Britain trained Indians to use their bodies as surveying instruments and map Tibet, which didn’t permit Westerners inside.

In the 19th century, Britain trained Indians to use their bodies as surveying instruments and map Tibet, which didn’t permit Westerners inside.

Indian spy-surveyors explored Tibet and brought back information to the British.

We know this much, and there are documents in which we can see the routes they took through Tibet.

Hilary Mantel said in her BBC Reith lectures that she allowed herself to imagine a character’s interior, but the exterior – the wallpaper in his room, for instance – had to be based on fact.

To the extent possible, I tried to follow this guideline.

The particulars of Balram’s life are imagined—how he thinks, his motivations—but the details of what cartography and travel entailed in that time are based on research.

I consulted archives in India and the UK to learn about surveying and the instruments used then.

Katherine defies Victorian gender norms yet still carries colonial privilege. How did you approach writing such a complex female explorer?

It was in some ways easier to write about Katherine because there are accounts by female explorers, some of whom travelled to Tibet in the 19th and early-20th centuries.

Being a woman, and hence facing the restrictions society placed on them, didn’t make these female explorers any less imperialist; their accounts, too, are condescending about, say, Indians.

I based Katherine on what I could learn about the female explorers through their accounts.

Katherine has an Indian mother, and so she is all too aware of how the privilege she holds is fragile.

The novel explores maps and cartography as tools of power. Do you see storytelling itself as a way to rewrite history?

I don’t look at it as rewriting history, but it is more about reconstructing aspects of history that are missing from the existing records and archives.

I don’t look at it as rewriting history, but it is more about reconstructing aspects of history that are missing from the existing records and archives.

Indian history was written by the British, who ruled India at that time, so the point of view we get of that time is an imperialist one.

How might that be different if we looked at it from the perspective of the colonised? What are the gaps in the archives?

Fiction can bring those moments back to life.

Tibet feels like a character in its own right. How did travelling there influence your writing and reshape the novel?

One of the things that was helpful for me to see in Tibet was the kind of sacredness with which Tibetans invested their land.

One of the things that was helpful for me to see in Tibet was the kind of sacredness with which Tibetans invested their land.

They look at lakes and mountains as sacred; they pray to them.

That kind of relationship with the natural world, which we don’t often see, was important for me to witness.

I felt moved by what I saw as the ways in which people respected their land and the natural world.

I think everyone can learn from this, especially in today’s age. And I tried to convey that relationship in the novel.

Chetak moves mysteriously between Balram and Katherine. What does he represent, and why was it important for him to exist between both worlds?

Imperialism was about stripping the colonised of all agency.

Not allowing the coloniser to fully understand who you are, or what your motivations and aims are, would also be a way to hold on to a self, and I hope Chetak’s story illustrates this.

The Last of Earth questions who gets called an “explorer”. Do you think these hierarchies still exist in travel and adventure culture today?

Looking at some of the stories coming out of Everest, where the Sherpas are the helpers and the Westerners are the conquerors, these divisions do exist to this day.

But there is clearly more awareness, and these categories are being challenged.

My novel is more interested in looking at whether there is anyone who should be called an ‘explorer’ in a landscape already populated by the people born in that land.

Both protagonists experience deep isolation across vast landscapes. How did you approach writing loneliness in such extreme settings?

Trekking at high altitudes can leave you with very little energy for conversation.

This meant that the characters would be alone with their thoughts for most of the time.

But I would not describe it as loneliness. Solitude can be fruitful.

You may be able to reconsider some of your earlier decisions or see your actions in a new light.

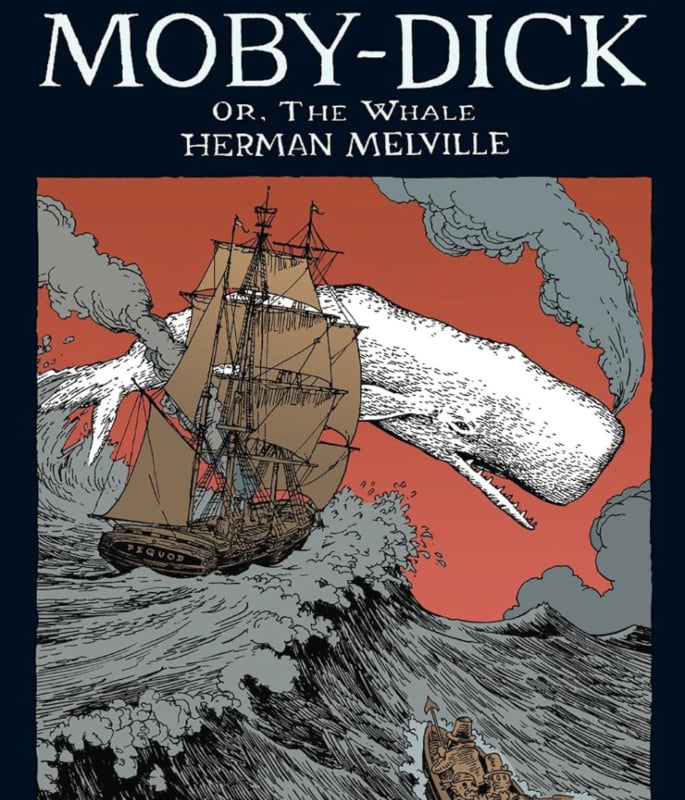

You’ve cited Kim and Moby-Dick as influences. What did these classics offer creatively, and what did you want to challenge or subvert?

Moby-Dick offered me the courage to write an adventure novel that was also unafraid of asking philosophical questions.

Moby-Dick offered me the courage to write an adventure novel that was also unafraid of asking philosophical questions.

It is a digressive account too, not a novel that jumps from one conflict to another.

Kim, on the other hand, has an action-packed plot and fully endorses British imperialism.

I wanted to challenge that, of course, but at the same time, I wanted to write characters with the same complexity that Kipling grants Kim in the novel.

For South Asian readers discovering your work, what do you hope they take away from Balram’s journey?

I hope it makes us think of all the ways in which the past continues to exert an influence over our imaginations and how we view ourselves.

I hope it will make us interrogate the relationship we have with the landscape.

Once upon a time, we viewed the land as sacred, whereas now, we seem to be consistently thinking of ways in which we can exploit it, often to our own peril.

At its heart, The Last of Earth is a meditation on memory, land and agency.

Anappara’s reflections invite readers to reconsider how colonial histories continue to shape identity, imagination and our relationship with the natural world.

For South Asians, Balram’s journey becomes a reminder that our past is not confined to imperial records.

It lives in landscapes, in silences, and in stories waiting to be retold.

By centring Indian experiences often erased from history, Anappara offers a quietly radical act of reclamation.

The Last of Earth by Deepa Anappara is published by Oneworld.