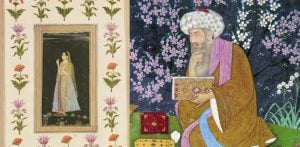

At the centre were the courtesans.

In the opulent palaces and bustling bazaars of medieval India, a world of artistry, power, and social complexity thrived.

At the centre of this world were women who were both revered and reviled: the performers, courtesans, and prostitutes.

Their lives existed in a dazzling paradox, celebrated for their culture and beauty, yet tightly controlled by male authority and state regulation.

Shadab Bano’s 2009 academic paper, Women Performers and Prostitutes in Medieval India, brings this world into sharp focus.

Through meticulous research, Bano uncovers a history far more nuanced than the popular imagination allows.

These women were masters of music, dance, and etiquette. They held sway over artistic and cultural life, yet their existence was constrained by societal and political pressures.

Their stories challenge modern assumptions about art, sexuality, and female agency in South Asian history.

To explore their lives is to confront uncomfortable truths about the blurred boundaries between the sacred and profane, the artist and the outcast.

These were women who entertained sultans, captivated nobles, and navigated a society that simultaneously admired their skills and condemned their trade.

Their world, though long gone, still resonates with questions about power, morality, and cultural authority.

Artist, Entertainer or Prostitute?

During the early Sultanate period, distinctions between performer and prostitute were far from clear.

Music and dance were markers of sophistication, entertainment, and physical pleasure, intertwining cultural refinement with personal desire.

This dual role placed female singers, dancers, and musicians in a precarious social position. Many were classified alongside prostitutes simply because they worked in the realm of pleasure.

Yet this “labelling” was not fixed.

Historical accounts reveal a complex hierarchy, where some women were celebrated as embodiments of high culture while others were condemned.

At the centre were the courtesans.

These women were highly educated in poetry, etiquette, and the fine arts. They were masters of music and dance and were distinct from common prostitutes, whose services were primarily sexual.

Still, boundaries often overlapped. A professional dancer might offer sexual favours, just as a prostitute might sing or dance to attract clients.

A woman’s social status was fluid, negotiated daily based on skill, patronage, and prevailing societal attitudes. Chronicles of the era reveal these complexities.

For instance, the 14th-century Delhi court established a sprawling enclave called Tarababad, the “city of music”.

This state-sponsored area housed male and female artists who were respected and even participated in religious ceremonies.

Such recognition was unusual, particularly for women who might otherwise be associated with prostitution.

In this context, art and sexuality existed side by side.

Women were not simply entertainers or sex workers; they were cultural authorities, shaping music, dance, and etiquette for the elite while navigating a precarious social hierarchy.

Patronage, Profit & Punishment

The state in medieval India was not a passive observer of this world. It acted as a patron, regulator, and moral arbiter, simultaneously fostering culture and enforcing control.

Rulers cultivated female performers as symbols of prestige.

Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq, for example, maintained 1,200 musicians, plus another 1,000 slave musicians.

Highly skilled performers, particularly slaves, commanded prices of 20,000 tankas or more.

Patronage extended beyond entertainment; it was a demonstration of power, sophistication, and cultural refinement.

Yet the state also directly had a say on prostitution.

Contemporary texts discussed male sexual desire and the need to regulate it to prevent social disruption. Prostitution was considered a necessary safeguard against the passions of “unruly men”.

However, Mughal-era rulers introduced stricter moral oversight. Prostitutes were sent to live in an enclosed neighbourhood called Shaitan Pura or ‘Devil’s Town’.

Licensing became stringent.

Men had to register before visiting a prostitute and taking a virgin required imperial approval.

Flouting these rules could result in capital punishment. This surveillance reflected medieval India’s obsession not only with women but also with controlling private morality among the elite.

Patronage and policing defined the female performer’s existence.

On one hand, she could be revered as an artist; on the other, her freedom and status were constantly circumscribed by male authority and state power.

A Tangled Hierarchy

Female performers operated within a rigidly defined social hierarchy, divided by caste, skill, and status.

According to Bano’s paper, 16th-century records from the court of Sultan Bahadur of Gujarat list multiple classes of dancing girls: domnis, paturs, kumachnis, parishans, and lulis.

Paturs were a celebrated Hindu caste of performers whose style, paturbazi, became synonymous with dance.

Lulis, in contrast, were Muslim performers.

These “free-born” women could be concubines of sultans, nobles, or gifted to other rulers, simultaneously prized as cultural assets and treated as property.

By the 17th century, the kanchanis emerged as elite performers in the Mughal court. They were distinguished from common prostitutes, performing at weddings and court events while retaining social esteem.

Manucci described over 500 kanchanis arriving at court in elaborately decorated vehicles, clothed in luxurious attire.

Bernier, another chronicler, emphasised that they were respected for their beauty and talent and “did not normally prostitute to even men of class”.

An amusing incident highlighted their exclusivity.

A French physician at court sought the company of a kanchan, but her mother repeatedly refused, fearing the loss of health and virginity. The matter caused “merriment” at court and required the emperor’s intervention.

This hierarchy reflected a subtle, negotiated system of power. Skill, education, and beauty could elevate a woman, while social perception and patronage determined her ultimate status.

Morality and the Mughal Court

While early Sultanate society tolerated fluid roles, the Mughal era marked a hardening of moral attitudes in medieval India.

Music and dance remained central to courtly life, but official discourse increasingly associated female performers with immorality.

The once-neutral term tawaif, once neutral, developed ambiguous and eventually derogatory connotations.

Abul Fazl’s account of Aram Jan, a performer called a luli, exemplifies this shift.

When noble Ali Quli Khan married her, Abul Fazl condemned the marriage, calling her a “street walker embraced by thousands” and ignoring her artistic and social achievements.

This reflected the broader Mughal moral stance, which increasingly defined acceptable female behaviour narrowly.

Imperial orders reinforced this.

Any young woman wandering the bazaars unveiled was sent to prostitution quarters. A woman who quarrelled with her husband could be declared “fit to be a prostitute”.

Marriage to dancers was discouraged, and concubinage was considered “unworthy of royalty.”

This period illustrates the tension between cultural sophistication and moral policing.

Women were celebrated for talent yet punished for perceived transgressions, revealing the tightrope of female existence under courtly authority.

A Contested Legacy

Despite stricter moral codes, societal attitudes remained varied.

The 18th-century diaries of Dargah Quli Khan depict Delhi as a city where pleasure and culture coexisted. Courtesans enjoyed respect, living in style and influencing social and political life.

Performers like Rehman Bai were notable for virginity, underscoring that artistry alone could elevate status.

Many courtesans entered noble households through marriage, wielding significant influence, and their kothas became centres of literary and cultural patronage.

Yet this intricate social order began to erode under British colonial rule.

Victorian moral frameworks reframed these women’s lives as evidence of “native sexual depravity”.

The nauch girl, once celebrated, became “amorous and vulgar”.

By the 19th century, the term tawaif was reduced to a generic label for prostitutes.

Colonial censuses, such as that of 1891, combined dancers and sex workers into a single category.

Centuries of nuanced distinctions were erased, leaving a legacy of shame that persists in South Asian society.

What had once been a respected, complex institution of artistry and entertainment was flattened into stigma, severing women from the cultural authority they once commanded.

The story of female performers and prostitutes in medieval India reminds us that history is rarely black and white.

These women were artists, cultural leaders, entrepreneurs, and survivors. They navigated a society that celebrated and condemned them in equal measure.

From Tarababad’s musicians to the licensed inhabitants of Shaitan Pura, their lives reflected shifting power, morality, and culture.

They challenged conventional categories of wife, mother, or daughter, creating a rich artistic legacy dismantled by colonial rule.

Understanding their complex history forces reflection on inherited prejudices and the continued marginalisation of women in the arts.

Their world may have vanished, but its echoes remain, demonstrating the enduring power of art and the ongoing struggle for female agency within constrained social structures.

Theirs is a story of resilience, creativity, and negotiation; a testament to the ways women shaped and survived the intricate cultural landscapes of medieval India.