an arrival has roughly a 1 in 17 chance of being returned.

The small boat crossings in the English Channel remain the most potent and polarising fixture of British political life.

For young British Asians, this debate often feels caught between a heritage of migration that built our communities and a modern desire for a system that functions with basic competence.

With the new UK-France “routes and returns” deal now in effect, the conversation has shifted from theoretical “stop the boats” slogans to the gritty reality of operationalising a treaty.

A report titled How We Can Actually Stop the Boats by the think tank British Future offers a deep dive into this new era of the asylum system.

Authored by Sunder Katwala and Frank Sharry, this paper argues that while the foundations of control are now laid, the government must be significantly bolder if it wants to see a genuine collapse in irregular arrivals.

The ‘Routes and Returns’ Reality

The Starmer-Macron deal and the resulting Treaty of July 2025 have fundamentally changed the mechanics of the Channel.

We are no longer in an era of pure enforcement-only “whack-a-mole”, where those stopped at the English border simply try again until they succeed.

The current system operates on a “one in, one out” principle: the UK returns a set number of people who arrive without permission, while simultaneously opening a controlled, legal route for a corresponding number to enter.

This is a radical departure from the previous government’s approach, which essentially created a backlog by refusing to process claims at all.

The report notes that the current pilot scheme is a “proof of concept”, but its current scale, removing roughly 50 people a week, is not yet enough to break the business model of the smuggling gangs.

Home Secretary Yvette Cooper has been clear that this is only the beginning:

“We are not putting an overall figure on this programme. Of course, it will start with lower numbers and then build, but we want to be able to expand it.

“We want to be able to increase the number of people returned through this programme.”

For the scheme to move from a pilot to a solution, it needs to reach a “tipping point” where the probability of being returned to France is high enough to make the thousands of pounds paid to smugglers a bad investment.

Currently, an arrival has roughly a 1 in 17 chance of being returned.

The research suggests that if this reached up to 50,000 authorised places a year, it would create a near-guarantee of return for those using illegal routes.

This strategy recognises that you cannot have control without providing a “queue” to join.

For many in the South Asian diaspora, whose families arrived via rigorous legal paths, the idea of a managed system resonates.

It moves the argument away from “should we help refugees?” to “how do we help them safely?”

By prioritising those most in need, including those fleeing the Taliban in Afghanistan, the government can demonstrate that it has reclaimed the border from criminals and returned it to the state.

Lessons from America

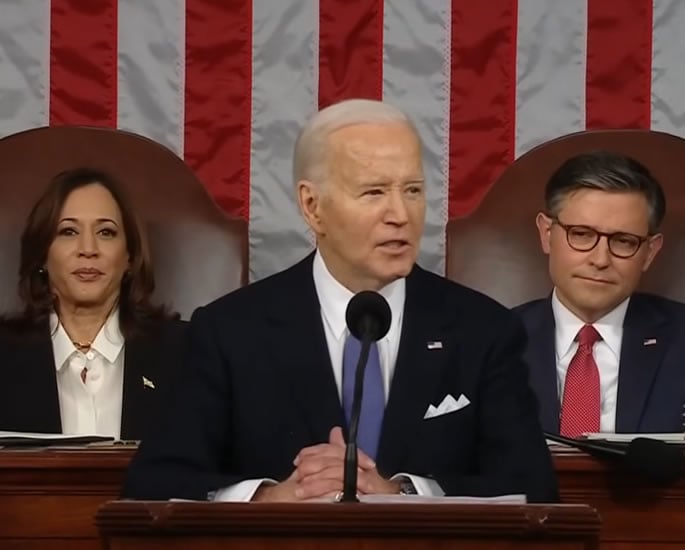

While British politicians have spent years looking to Australia for answers, the report argues that the most successful case study for the UK is actually the United States in 2024.

Under then-President Joe Biden, the US administration achieved something many thought impossible: a 77% reduction in illegal border crossings between December 2023 and August 2024.

This wasn’t achieved through a wall or purely through rhetoric, but through a “three-pronged approach” almost identical to what the UK is now attempting.

It combined intense diplomatic cooperation with Mexico, a tough stance on irregular crossings, and crucially, a substantial official scheme where people could apply for humanitarian visas from their home countries or a place of safety.

The US data shows that when migrants were offered a “safety valve”, like the CBP One app to schedule appointments at ports of entry, they opted for the queue.

The smugglers’ business model nearly collapsed because the “product” they were selling was suddenly more dangerous and less likely to succeed than the official legal route.

The report highlights that “Biden’s programme was not just swapping illegal migration for legal migration – it was reducing the overall numbers coming to the US by changing migrants’ decisions about coming”.

This is a vital lesson for the UK. If the government can provide an accessible, legitimate route, they shrink the market for the gangs.

However, the American experience also serves as a warning.

The Biden administration’s success came “too little, too late” to change the political narrative before their election.

They had spent three years being defensive, allowing their opponents to brand them as the party of “open borders”.

Keir Starmer’s government must avoid this trap by leaning into the success of the UK-France deal early.

To actually “stop the boats”, the UK must move from a cautious pilot to a game-changing surge in authorised admissions that makes the irregular route an unattractive gamble.

Public Consent

One of the most enlightening aspects of the report is its analysis of the British public’s mindset.

Using the Ipsos/British Future Immigration Attitudes Tracker, the researchers identified a large “Balancer Middle” group that makes up about half the population.

This group isn’t driven by the extreme hostility often seen in social media comments, nor by an “open borders” ideology. Instead, they want a system that balances control with compassion.

They are frustrated by the failure of successive governments to “get a grip,” but they do not want to abandon Britain’s tradition of protecting those fleeing persecution.

The polling reveals a surprising level of support for the new “routes and returns” deal.

Approximately 55% of the public supports the principle of a capped number of people being admitted via authorised routes in return for France taking back those who cross in small boats.

Most strikingly, this support transcends traditional party lines.

Among Reform UK voters, a majority of 53% are willing to support this deal.

This suggests that even those most concerned about immigration numbers are willing to accept legal routes if it is the price of ending the chaos of the Channel.

The report notes: “It is a depolarising proposal which appeals to 62% of Remain and 57% of Leave voters.”

Younger people are significantly more sympathetic to the plight of those in the boats, but they also value competence.

The “Balancer Middle” believes it is reasonable to ask asylum seekers to join a line, provided that a line actually exists.

By scaling up the UK-France deal, the government can satisfy the public desire for order without “ripping up treaties” or abandoning the Refugee Convention.

The research suggests that the Prime Minister has more “permission to be bolder” than he might think, as long as the policy is framed as a way to restore order and fairness.

Moving Beyond the Australian Fantasy

For years, the “Australian model” of offshoring and “turnbacks” has been used as a political sledgehammer in the UK.

The report, however, dismantles the idea that Britain could ever truly emulate Australia’s example. Australia spent £4.3 billion to send just 3,127 asylum seekers to Nauru or Papua New Guinea, a cost of over £1.4 million per person.

For the UK, dealing with much higher flows, the logistics and financial costs of such an attempt would be astronomical.

Furthermore, Australia’s geography allowed for “turnbacks” because it had agreements with Indonesia to accept boats back.

The UK has no such luxury; without a deal with France, “turnbacks” are a legal and physical impossibility in the narrow, busy shipping lanes of the Channel.

The report argues that the British experience of “political plagiarism”, importing slogans like “Stop the Boats” without the corresponding geography or agreements, has led to years of failure and public frustration.

Instead of chasing the Australian ghost, the UK must focus on its European reality. The 2025 Treaty with France is a step toward a more assertive European-wide strategy.

With the new EU Asylum and Migration Management Regulation (AMMR) coming in 2026, there is a growing consensus that “externalised processing” and “first country of entry” rules need to be part of a broader system of solidarity.

Ultimately, the path to stopping the boats lies in international cooperation, not isolation.

The report concludes that the “routes for returns” principle is the most viable way to rebuild public confidence.

It offers a “mend it, don’t end it” case for the international refugee system as we approach the 75th anniversary of the Refugee Convention in 2026.

For a generation of British Asians who have grown up in a multi-ethnic Britain, the goal is a system that reflects our values: one that is orderly, humane, and above all, effective.

The UK-France deal provides the framework; the next three years will determine if the government has the courage to make it work at the scale required to finally end the era of the small boats.

The crisis in the English Channel is not an insurmountable act of nature, but a policy challenge that requires a move away from symbolic distractions.

The British Future report provides a clear-eyed assessment: the new deal with France is the right foundation, but it must be scaled up to at least ten times its current size to truly disrupt the smuggling gangs.

By combining strict enforcement with genuine, safe routes for refugees, the UK can move past the toxic polarisation of recent years.

For people in Britain, seeing a government that can finally “get a grip” through competence rather than just rhetoric would be a welcome change.

As we look toward the future of refugee protection, the message is clear: international cooperation is not a sign of weakness, but the only sustainable way to restore control to our borders.