"the body utilises amino acids in the very same manner”

Walk down any supermarket aisle today and you will notice a distinct shift, with bold ‘protein’ labels on packets of chocolate bars, biscuits, yoghurts, and even breakfast cereals.

What was once the preserve of bodybuilders and elite athletes has filtered down to the everyday consumer, transforming protein into the undisputed macronutrient of the moment.

We seem collectively obsessed with the idea that more is always better.

This is driven by an assumption that adding protein to a processed snack automatically neutralises its less desirable attributes.

However, as grocery shelves groan under the weight of these fortified products, a critical question arises regarding whether they offer genuine nutritional value or if we are simply buying into a cleverly constructed marketing halo.

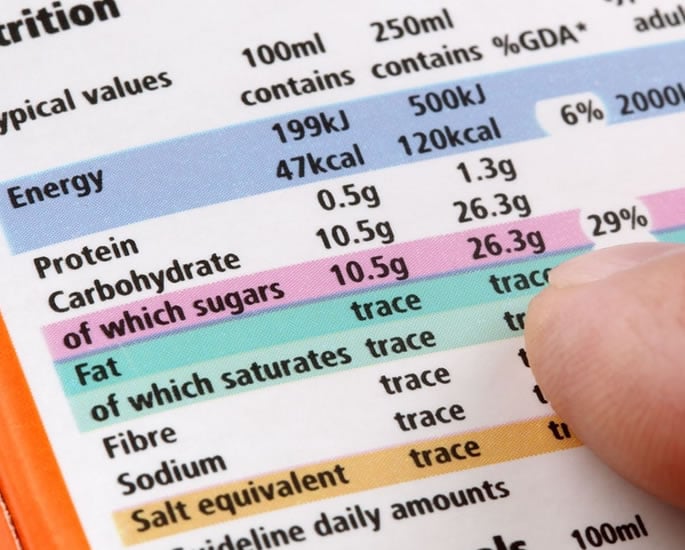

Decoding the Label

Understanding what actually constitutes a protein-fortified product is the first step in navigating this saturated market.

The term is tossed around loosely, yet the regulatory framework governing it can be surprisingly complex, depending on where you reside.

In India, for instance, strict criteria apply before a brand can make such bold claims.

According to Deepali Sharma, Clinical Nutritionist at the CK Birla Hospital, Delhi, a product must meet specific thresholds to earn the label.

She notes that Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) rules dictate that any fortified product must provide at least 15% of the recommended daily allowance (RDA) of the added nutrient per serving.

This regulatory baseline is intended to protect consumers from products that merely dust a biscuit with a negligible amount of whey powder to justify a price hike.

Sharma adds:

“The label must clearly state the precise source and quantity of additional protein per serving.”

This is a crucial distinction for consumers to look for, regardless of their location, as it separates genuine functional food from marketing fluff.

In the UK and Europe, similar stringent guidelines exist where a product can only claim to be a “source of protein” if at least 12% of the energy value of the food is provided by protein, and “high protein” if that figure rises to 20%.

Despite these norms, experts caution that loopholes remain prevalent. A common issue is the discrepancy between the front-of-pack promises and the nutritional reality on the back.

Many snacks that lean heavily on protein branding contribute a meagre 2-5 grams of protein per serving.

For an adult looking to aid muscle recovery or satiety, this amount is statistically insignificant.

Sharma explains that noticeable improvement happens only when snacks offer around 8-12 grams of high-quality protein per portion.

Consumers are often paying a premium for a protein dosage they could easily surpass with a handful of almonds or a small glass of milk.

Quality and Compromise

To understand whether these snacks deliver, one must look beyond the gram count and examine the source of the protein itself.

It is not enough for a bar to simply contain protein; the body must be able to absorb and utilise it effectively.

Manufacturers typically rely on isolated powders to boost their numbers.

Commonly used protein sources include whey protein concentrate, casein, soy protein isolate, pea protein, and chickpea or lentil protein.

Among these, dairy-derived options like whey and casein generally offer the superior amino acid profile and biological value required for efficient muscle repair.

However, the rise of plant-based diets has pushed manufacturers toward soy, pea, and lentil isolates.

While these are excellent ethical alternatives, they can sometimes be incomplete proteins or harder for the body to digest unless they are combined strategically to offer a full range of amino acids.

Isolated proteins, such as those used in bars and shakes, also digest more quickly, which may support faster muscle recovery.

“But overall, the body utilises amino acids in the very same manner”, says Sharma, suggesting that while the metabolic outcomes can differ slightly from whole foods, the fundamental biological process remains consistent.

The major trade-off with fortified snacks often lies in what accompanies the protein.

To mask the naturally chalky or bitter taste of protein isolates, manufacturers frequently resort to ultra-processing. This is where the nutritional profile can become murky.

Sharma highlights several misleading practices on packaging, including hidden sugars and excessive sodium.

To keep calorie counts low while maintaining sweetness, many bars are loaded with sugar alcohols or artificial sweeteners, which can cause digestive distress in some people.

Furthermore, high-calorie or high-fat formulations are often masked as ‘healthy’ simply because the protein content is highlighted in large font.

A cookie containing 10 grams of protein but loaded with saturated fat and refined sugar is, nutritionally speaking, still a cookie.

Consumers must also be wary of vague or undisclosed protein sources.

If a label essentially lists a generic “protein blend” without specifying the ratios or types, it becomes difficult to assess the quality of the amino acids being consumed.

The lack of amino acid profiling on many mainstream snacks means you might be getting a high quantity of protein, but not necessarily the quality required for optimal health.

The Whole Food Alternative

The widespread presence of protein-fortified products makes it seem like everyone needs more protein, but research shows this is not usually true.

For most adults who eat a balanced diet and are not very active, protein deficiency is rare.

Marketing often plays on fear rather than real nutritional need. However, some groups can benefit from convenient protein options.

Sharma points to children, older adults, vegetarians and vegans with low protein intake, athletes, and people recovering from illness.

In South Asian communities, diets are often high in carbohydrates such as rice, flatbreads, and potatoes, which can leave protein intake lower.

Vegetarians who struggle to meet daily needs with daal and paneer alone may find a good-quality protein bar helpful.

Older adults, who often eat less and lose muscle with age, can also use these snacks to maintain strength without eating large amounts.

Using these products without care can cause problems. People with kidney disease, metabolic conditions, or dairy and soy allergies should avoid them or use them carefully.

High levels of protein can put extra strain on weakened kidneys.

Relying on processed snacks can also replace healthier whole foods. A bowl of chickpeas or a boiled egg provides not only protein but also fibre, vitamins, and minerals that a processed bar cannot match.

For healthy people who already get enough protein, fortified snacks are unnecessary and often cost much more than whole foods.

As the industry grows, the need for regulation becomes more important.

Current FSSAI guidelines provide only a basic structure and lack detail.

Sharma says: “More stringent regulations on minimum thresholds of protein percentages, better monitoring of claims, and clearer definitions are required to prevent misleading labels.”

This concern is shared worldwide.

As food technology develops, the line between health food and sweets is becoming less clear. Protein-fortified water, crisps, and even pastries are now common.

Without stronger rules on marketing, consumers risk being misled by attractive packaging rather than real nutritional value.

Protein-fortified snacks are neither a cure-all nor a dietary danger. They are simply a convenient option.

When chosen carefully by checking for at least eight grams of protein, low sugar, and clear, familiar ingredients, they can help meet needs in a busy life.

However, they should never replace the full nutritional value of whole foods.

Before trusting claims of peak performance, it is always worth turning the packet over and reading the ingredients. The real truth is found there, not in the slogan.