“They just blend into all the other negative comments"

Skin whitening in South Asian circles has long been explicit and tangible. It sat on bathroom shelves in the form of lightening creams and toners that promised better jobs and ‘good’ marriage matches.

But in the modern day, such creams are replaced by digital editing apps and filters found on our smartphones.

This shift has allowed colourism to continue impacting younger South Asian women through more subtle, yet equally damaging, terminology such as ‘glowy’ or ‘brightening’.

Moreover, the intangible nature of these digital edits has made them more elusive. Even casual photos at a café or a wedding reception now pass through a quiet layer of editing before they are shared among social media followers.

DESIblitz looks at digital whitening and the impact it has on South Asian women.

How did the Obsession with Fair Skin Evolve?

Colourism in South Asia has a long history, dating back to social hierarchies and reaffirmed by colonialism.

In pre-colonial society, skin colour was largely a class distinction, with lighter skin being associated with a higher social status.

Contrarily, darker skin was linked to a lower status, with association to over-exposure to the sun as a result of more rigorous outdoor labour such as farming.

This divide was cemented when the East India Company took control of large parts of India in the 18th century.

British rule brought a racial hierarchy that solidified whiteness at the top.

Fair skin became a symbol of modernity, education and authority. Fair-skinned Indians were treated more favourably, both socially and professionally.

Skin-lightening creams like Fair & Lovely began flooding the market during the 1970s, and with them came the promise of upward social mobility.

Adverts perpetuated the notion that lighter skin would lead to better jobs, marriages and overall lives.

These creams gave colonial beauty ideals a physical form that could be bought and applied, and whose results could be visibly reflected in one’s mirror.

Over time, and with increased awareness and conversations regarding racism and colonialism, these notions were drawing wider scrutiny.

Brands began rebranding themselves through language changes such as ‘brightening’ and ‘glow’ instead of ‘whitening’ and ‘fair’. So, whilst the core messaging prevailed, it became less tangible and more digital.

As a result, the notion of fair skin is better passed through generations, sometimes fuelled by family members.

In a 2023 report, a 31-year-old woman of Pakistani ethnicity revealed:

“Sometimes extended family would compare and ask questions like, ‘How come your sister is so much lighter than you?’”

“And I remember somebody asked me, ‘How come you’re darker than your sister? Do you not scrub your skin properly in the shower?’”

This parallel drawn between darkness and uncleanliness is one that commonly resurfaces within colourist narratives across various cultures, not only in South Asia.

One controversial example involved a Chinese detergent advert which showed a black man being thrown into a washing machine and a lighter-skinned Asian man exiting.

Today, such blatant acts of racism are more easily identifiable and condemned. But colourism, a related but distinct issue, operates in quieter ways, and typically within one’s own communities.

Reflecting on this, Sara told DESIblitz: “Growing up, you don’t even register these comments as a form of racism, especially since minority communities seem to believe they’re immune to being racist somehow.

“They just blend into all the other negative comments aunties would make about someone’s looks, like their hair, or clothes, or body.

“It’s not til you’re a bit older and more educated that you realise just how problematic it is and where it stems from.”

Dr Divya Khanna, who specialises in dermatology, tried to understand this prevalence of colourism within the Indian diaspora.

She found most respondents were driven by an open, internalised racism, marked by shame and stigma against dark-skinned members of the community.

But “with the third generation, there were still remnants of some fair skin ideals, but watered down”.

One participant admitted a preference for a partner with “fairer skin”.

This shows that the underlying colourist preferences and conceptualisations of beauty have not disappeared. They have simply diffused themselves across new settings and platforms, particularly into social media and dating apps.

How Digital Whitening Works

Skin lightening’s evolution from ointments to smartphones was not instant.

As public pushback against fairness cream brands grew and companies softened their wording, social media platforms were on the rise, and with them came the normalisation of built-in filters.

Instead of buying a product and waiting weeks for ‘results’, people could now achieve that same lightened look instantly.

And due to the wide variety of filters and edit options, using them felt harmless.

Editing photos is usually a chain of fixes: lift exposure to ‘help’ a dim room, cool highlights to calm shadows, smoothen textures.

On many smartphones and social media apps, editing photos is very easy to do, with features coming as default.

Even apps marketed for ‘professional editing’ or wedding retouching quietly carry the same defaults.

When asked about the process of using filters, Zara said:

“When most of the filters already have a base level of skin whitening going on, you stop differentiating them based on that, you don’t even realise it anymore.

“You just see it as choosing from the sea of whitewashing filters depending on which makes you look the best, rather than trying to find one that doesn’t whitewash you even a little.”

And so, the whitening effect of such filters increasingly blends into the background, becoming the norm for South Asian users.

It is no longer a conscious choice to edit one’s pictures to look fairer; it becomes an imposed byproduct of someone turning to filters to perhaps correct another insecurity.

Creams announced themselves, but filtering has evolved the internalised obsession with fairer skin, cutting out time and effort.

Societal & Cultural Pressures

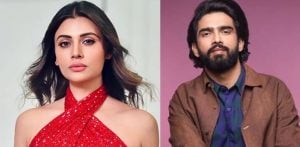

The obsession with fairer skin can lead to pressure coming from all directions, whether it’s family members, social media or partners.

Actress Charithra Chandran spoke about the issue, saying:

“No one let me forget that I was dark-skinned growing up.”

She also shared how “her grandparents allowed her to play outside only in the morning or in the evening to avoid sun exposure”.

Even the pursuit of a romantic partner is deeply embedded within these standards.

Praise still circles around looking ‘fresh’ or ‘glowing’, and weddings can revive old fairness talk.

For those opting for the traditional, arranged route in finding a partner, they will find that skin colour is a recurring factor in the marriage ‘biodatas’.

Similarly, those attempting more modern methods, such as dating apps, will run into the same problem.

According to Dr Khanna, participants reported a higher likelihood of getting hits on dating apps for lighter-skinned men and women.

Social media simply extends these rhetorics onto wider platforms.

Priya* explained how this disparity was especially noticeable with the ‘clean girl‘ aesthetic trend.

She said: “It’s very telling when white women on TikTok can popularise oiled, slicked back hair as ‘put-together’ and ‘clean’.

“Meanwhile, South Asian women who have been doing it for centuries, have had to deal with being called ‘dirty’ or ‘greasy’ for the same thing.”

When it comes to filtered beauty on social media, certain algorithms reinforce “Westernised, often Eurocentric beauty standards”.

Since the algorithm rarely celebrates these raw images, trying to establish a social media presence often means walking that fine line between authenticity and conformity.

In some cases, friends expect selfies to be “tidied up”.

Aisha* spoke about how “if I ever try to take a picture without filters on, my friends usually hate it and ask me to put one on”.

She added: “And you just go along with it either because most filters apply to everyone and you don’t really have a choice, or because it’s jarring if you’re the only one without it.”

That is why “just be confident” advice rarely sticks.

The pull is not only vanity. It is how apps are built, how friends react, and how attention online is earned.

Impact on Identity & Self-esteem

The impact of these standards runs deeper than most people may acknowledge.

Whilst filters and edits appear to be small choices, over long periods, they have the power to change how South Asian people see themselves.

Each tweak seems harmless, but when stacked up, the overall result is lighter, more uniform skin that erases the natural richness and contours of the face for a ‘smoother’ complexion.

Repeated use of filters can lead to normalisation, meaning edited photos begin to feel like the original ones.

Aisha continued: “When even the standard for natural selfies is this flawless skin with no dark circles or hyperpigmentation, not using at least a slight ‘natural’ filter makes you look tired or haggard.”

Additionally, Iqra recalled: “When I used to use filters a lot and I’d take selfies with someone who didn’t, I’d hate every picture… I didn’t even feel like I looked like myself.”

Unlike whitening creams, which would produce a visible difference in skin tone, digital whitening only exists online.

This results in feelings similar to those of Iqra’s, a degree of facial dysmorphia, where one feels disconnected from the version of themselves they see in the mirror.

This can have long-term effects on self-esteem and it is only amplified for individuals whose natural skin tones already set them outside the narrow definitions of beauty that are perpetuated both locally and globally.

Ultimately, the damaging effect of digital whitening is problematic when these parallels between lighter skin or using a ‘natural’ filter begin seeping into the subconscious.

Challenging Digital Whitening

Celebrities and creators, such as Charithra Chandran and Deepica Mutyala, are pushing back against these notions.

As well as posting unedited photos, they also explain how to set exposure without washing out undertones, or pick a foundation to match, not brighten skin.

In an interview with Grazia, makeup mogul Deepica Mutyala powerfully states that “your skin tone represents your culture, your roots, and your identity. It is our mission to wear it proudly”.

Campaigns that highlight deeper shades widen the idea of what counts as aspirational.

One small shift is to change the vocabulary because comments fuel edits more than we realise. Even small reframing, like pointing out how sunlight brings out warmth or depth, can subtly change expectations.

Though it may seem intimidating at first, it is important to tell friends and photographers who edit your photos that you do not want your skin lightened.

Not only is this boundary setting essential to oneself, but it can also be instrumental in sparking open conversations.

Priya’s own experiences reflect this as she discloses how she “didn’t like how dependent I was becoming on filters, so I made myself get used to not using them”.

She added: “I began asking my friends if we could take some pictures without filters, more because I actually started hating how they look than trying to make a statement.

“Just by voicing that, I felt like my friends got more comfortable opening up about their own struggles with insecurities because of this over-dependence on filters.”

Through this, it becomes clear how small habits can spread.

It’s safe to say that edits and filters themselves aren’t the problem; they are symptoms of a greater issue.

It’s the quiet link between “better” and “lighter” that is doing the damage, and which is being woven into the ways these tools are built and used.

Tracing digital whitening to its roots of colonial beauty ideals and whitening creams can help in recognising damaging patterns.

It becomes clear how persistent and adaptable these skin tone preferences are, reappearing in subtler and more modern forms with the changing times.

Yet, the deeply rooted weight of prevailing family attitudes and societal influence may not feel subtler to individuals who have become dependent on these tools to satisfy external expectations.

The long-term effects on one’s self-image and self-esteem make the topic of digital whitening equally pressing as its more obvious predecessors.

Ultimately, the persistence of colourism isn’t the work of any single product or platform. It relies on each individual’s everyday choices, shaped by history and culture. Choices that also have the power to shape history and culture, whether by reinforcing old ideas or challenging them.