It soon established deep roots in South Asian craft.

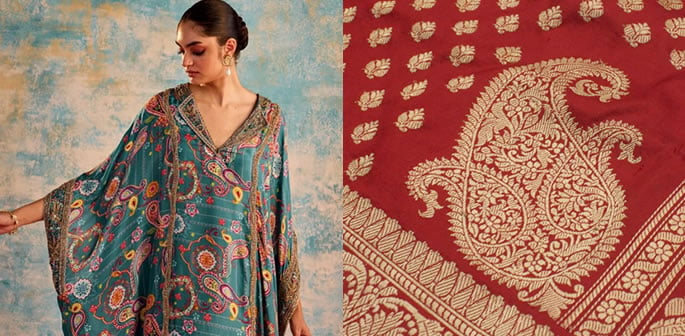

The classic Paisley design, with its curved point and petalled edges, is instantly recognisable.

But despite what the name suggests, this curling teardrop originated far from the Scottish town, finding its beginnings in Persia and South Asia.

Centuries apart and continents away, the shape stays familiar even while the world around it shifts.

The pattern has lasted because it can blend into various contexts and environments, it’s easy to adapt and hard to mistake.

Yet, whilst the shape remained the same, the Paisley has also undergone many shifts of its own, rarely staying put. With every change of location also came a change in meaning and identity.

Therefore, in tracing the Paisley’s path through its wide-spanning history and global usage, we uncover a story that mirrors the world’s own shifting pattern of ideas.

Origins in Persia and South Asia

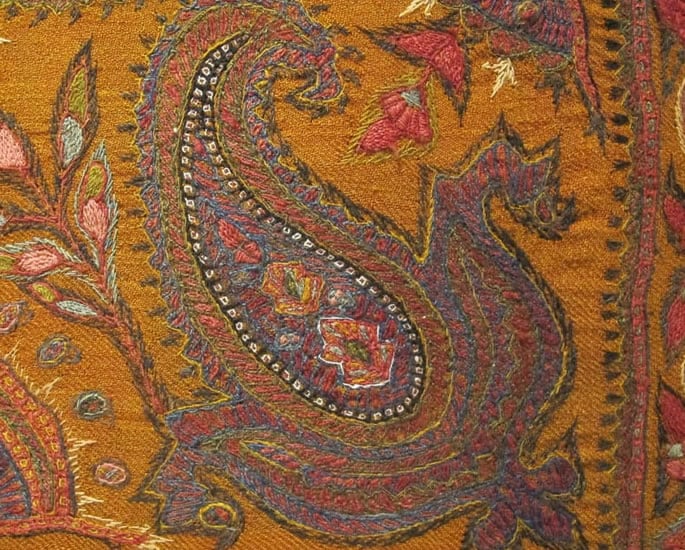

Before it was known as Paisley, the pattern was known as ‘boteh’ or ‘buta’ from its earliest origins in Persia.

The word points to plants, sprigs, clusters of leaves, and new growth, making it a symbol of life and continuity.

It soon established deep roots in South Asian craft. There, the Paisley made a long-lasting home for itself among the weavers of Kashmir, where the iconic cashmere pashmina shawls were made.

When complete, a shawl became proof of patient hours, skilled hands and mastery passed through generations.

Noble people draped them not only for elegance but because the fabric itself signalled status, wealth and the power to commission such artistry.

From Kashmir, the Paisley spread across the Indian subcontinent. It was found everywhere from bridal henna in Gujarat to the embroidered edges of sari borders in Rajasthan.

The boteh’s style changed as tastes changed, with loose leaf shapes and mango curves growing sharper and more stylised. The outline tightened until it settled into the droplet we recognise now.

Woodcarvers tucked it into door frames and headboards, while the design simultaneously made its way onto festival outfits, wedding attire and everyday wear.

Long before the rest of the world adopted it, South Asia had lived with the Paisley for generations.

As the Paisley evolved, so did its meaning. While some saw it as a seed sprouting into life, embodying growth and fertility, others viewed it as a flame symbolising life’s cyclical and infinite nature.

Trade Networks and Colonial Circulation

Europe first encountered the pattern through trade in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Ships carried textiles from India to Britain, the most prized being Kashmiri shawls. The East India Company brought them into ports where goods from the colonies drew eager buyers.

In British drawing rooms, the shawls quickly became a form of social currency.

Light, soft and vividly patterned, they allowed women to signal taste and wealth, while men collected them as proof of worldliness.

As the boteh arrived in Britain, its beauty on the surface often eclipsed its roots in tradition, culture and the skilled hands that had woven it.

None of this existed outside power – the British Empire made its circulation possible.

Trade transformed cultural signs into commodities, reshaping their meaning along the way.

In Britain, the boteh acquired new associations, speaking more of empire than origin.

It became a fashionable import, a symbol of worldliness and wealth for the upper classes who could acquire these exotic ‘Oriental’ novelties.

Industrialisation

In the early 19th century, demand for Kashmiri shawls began to outstrip what native artisans could produce.

With industrialisation underway, mills in the Scottish town of Paisley were opened to meet the growing appetite for machine-woven replicas.

New looms allowed the look to be reproduced quickly and at a lower cost, changing who could wear the design. What had once been a luxury for the elite now reached the expanding middle class.

The Scottish boteh-embroidered shawls lacked the finesse of Kashmiri craftsmanship, but that did not matter. Instead of competing on intricacy, they offered accessibility. Mass production carried the iconic curve into wardrobes across Europe.

As the mills prospered, the town’s name became inseparable from the pattern.

In the process, the boteh lost not only its intricate handwoven quality but also its original name. A motif born of Persian and Kashmiri craft was now diluted and industrially rebranded.

This loss was not just cultural; it affected livelihoods.

Many handloom workshops struggled to compete with mechanised weaving. Techniques slipped from everyday use even as the pattern flooded the market. The curve advanced, while its original makers were left behind.

Efforts are now underway to address this. Designers and heritage advocates are campaigning for credit, protection, cooperative models, and museum partnerships to keep older methods alive.

These initiatives coexist alongside a global market that thrives on open use, creating an ongoing tension within the pattern’s story.

Original handwoven shawls retain their prestige as heirlooms, prized for depth and detail.

Meanwhile, machine-made versions have entered everyday life, allowing the Paisley pattern to continue evolving with the times.

The Psychedelic Motif

This design does not cling to a single meaning; it slips between interpretations.

Initially, it represented nature, symbolising fertility and eternity.

In Persia, it belonged to palaces and sacred spaces, while in South Asia, it was both ceremonial and ordinary, appearing in temples and markets alike.

The tendency to attach meaning to the Paisley continued in the West.

By the 1960s, it found itself at the centre of a cultural storm it had not created, yet fit into effortlessly. Young people sought symbols outside the structures they were trying to challenge, and the swirling curve, with its ties to non-Western traditions, offered exactly that.

During this revolutionary decade, the Paisley came to embody much of the rebellious and experimental spirit of the swinging 60s.

Rock and roll, and musicians like The Beatles, popularised vivid and psychedelic patterns, often featuring the Paisley curve. It adorned flowy shirts, scarves and dresses, worn everywhere from music festivals to anti-war and civil rights marches.

Following the rise of rock and roll, the Paisley became an emblem of the Hippie movement between the 1960s and the mid-70s.

These movements celebrated unity, as activists, artists and subcultures joined to champion cultural acceptance and resist structures that sought to divide them.

Because its history was already layered, the Paisley could carry multiple messages at once.

Its flexibility allowed it to be claimed by many. A pattern that had once travelled through empires and industries now found new purpose, this time in defiance of many of those same systems.

It shifted from a marker of trade and a luxurious souvenir of colonial expeditions to a visual symbol of middle-class expression, protest, cultural fusion and freedom.

Patterns can be stripped of their original contexts, but they can also be refilled with new meaning, shaped by the urgencies of the present. Paisley has proved to be one of those.

The Paisley Today

The motif’s presence today stretches far beyond its original cultural and colonial circuits.

In the latter half of the 20th century and into the 21st century, it has been absorbed into mainstream fashion houses, global design archives, digital media and diasporic cultural expressions.

Luxury and fashion houses began incorporating Paisley into their visual identities in the late 20th century.

Etro, founded in Milan in 1968, made the pattern a signature.

Burberry, Hermès and other European labels used it in scarves, jackets and accessories, pairing an ancient motif with a language of modern luxury.

Through this process, Paisley became shorthand for a certain cosmopolitan timelessness, often detached from its Persian and Kashmiri roots.

Digital reproduction accelerated this detachment. In fast fashion, the pattern became a recurring print, mass-produced across garments and festival wear.

Its circulation on digital pattern libraries and stock image sites made it freely available to designers worldwide, further cementing its status as a global visual language.

Diasporic communities also carried the pattern into hybrid cultural spaces.

In the UK, Canada and the US, the pattern often appears in wedding attire that blends lehenga embroidery with contemporary silhouettes.

It has also resurfaced in everyday fashion among 2nd and 3rd-generation immigrants. For instance, the rise of pashmina hijabs and the blending of a Paisley print kurta with jeans and trainers.

These modern uses show that the Paisley is a symbol of preservation.

Its cultural and traditional roots have merged with its later revolutionary associations to create a symbol that is versatile and enduring.

For the younger South Asian diaspora, it presents itself as a bridge between heritage and modernity, showing how identity can adapt without fading.

The Paisley design’s history is cultural, but it is also economic. What began as slow handwork in Kashmiri workshops now runs through factories and shipping lanes.

A pattern that once took months to weave can be printed in minutes and arrive through Amazon’s next-day delivery. That ease makes it a staple.

Paisley’s path echoes a wider story about how culture travels.

A regional South Asian design became global and gathered new meanings that alternated between being complementary and contradictory.

Its history is not just about beauty, but also about power and movement.

Designs travel, shift ownership, and evolve in meaning. They carry memories and leave traces behind. The Paisley embodies all of this within a single shape, fully reflecting its original symbolism of infinity.