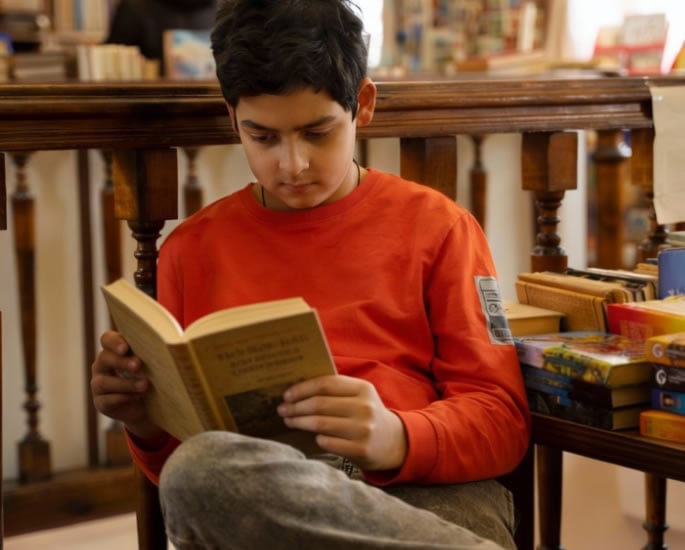

"playing video games can actually help boost intelligence."

For decades, the narrative around screen time among children has been dominated by warnings: too much can stunt development, harm attention, or reduce academic performance.

But research suggests the story isn’t so clear-cut.

A study of nearly 10,000 children in the United States found that playing video games may offer a small but measurable boost to intelligence.

While the difference isn’t dramatic, it challenges the assumption that digital entertainment is inherently harmful to young minds.

The research also highlights the need to reconsider how we think about screen time, genetics, and childhood development.

What the Research Shows

Researchers from the Netherlands, Germany, and Sweden analysed screen time habits for 9,855 children aged nine and ten as part of the ABCD Study.

On average, the participants reported spending 2.5 hours daily watching TV or online videos, an hour playing video games, and half an hour socialising online.

The team then examined data for over 5,000 children two years later, focusing on cognitive performance.

Children who spent more time than average on video games recorded a 2.5-point IQ increase over the average rise in intelligence.

This boost was measured through tasks assessing reading comprehension, visual-spatial processing, memory, flexible thinking, and self-control.

Importantly, the study did not distinguish between types of games, such as mobile or console, and only included children in the United States.

The research team wrote: “Digital media defines modern childhood, but its cognitive effects are unclear and hotly debated.”

Neuroscientist Torkel Klingberg from the Karolinska Institute in Sweden said:

“Our results support the claim that screen time generally doesn’t impair children’s cognitive abilities, and that playing video games can actually help boost intelligence.”

The Importance of this Study

The researchers emphasise that previous conflicting studies often overlooked critical factors.

Small sample sizes, varying study designs, and the failure to account for genetics and socio-economic background have skewed results in the past.

Researchers noted: “We believe that studies with genetic data could clarify causal claims and correct for the typically unaccounted role of genetic predispositions.”

Klingberg added: “We didn’t examine the effects of screen behavior on physical activity, sleep, well-being, or school performance, so we can’t say anything about that.

“We’ll now be studying the effects of other environmental factors and how the cognitive effects relate to childhood brain development.”

While the IQ gains observed are modest, the findings reinforce the idea that intelligence is not a fixed trait.

They also suggest that the debate over how much screen time is appropriate for children should be informed by evidence rather than fear.

Watching TV or browsing social media showed no clear impact, positive or negative, on intelligence, indicating that not all screen time is equal.

This research challenges long-held assumptions about gaming and childhood intelligence.

While it does not prove causation, it shows that moderate video gaming may contribute to cognitive development, at least in some areas.

Parents, educators, and policymakers should take note: blanket restrictions on screen time may be oversimplified.

Instead, understanding the types of digital engagement and considering individual circumstances could be a more effective approach.

As Klingberg and his team continue to explore environmental and developmental factors, one thing is clear – intelligence is shaped by a combination of nature, nurture, and, sometimes, play.