he was de-aged from 70 to 30 for a scene.

Indian cinema is undergoing a seismic shift as artificial intelligence moves from the realm of science fiction into the heart of the production suite.

Across Mumbai, Chennai, and Kochi, filmmakers are integrating AI into their movies.

While Hollywood recently grappled with industry-wide strikes over digital replicas, the Indian film fraternity has largely adopted a more pragmatic, if not enthusiastic, approach to these emerging technologies.

This transition is perhaps best personified by screenwriter-director Vivek Anchalia, who turned to AI when traditional producers showed little interest in his vision.

By leveraging platforms like ChatGPT and Midjourney, Anchalia bypassed the standard studio machinery to craft Naisha, a project on his own terms.

His journey serves as a blueprint for a new era where technical barriers to entry are dissolving, though not without sparking intense debate regarding the preservation of human artistry.

The Democratisation of the Director’s Chair

For decades, the high cost of production served as a formidable barrier for aspiring Indian filmmakers.

Vivek Anchalia’s experience with Naisha suggests those days may be ending.

Anchalia, who also writes lyrics, possessed a library of unreleased songs that required a grand Bollywood-style visual canvas.

When traditional funding proved elusive, he turned to an AI-enhanced pipeline to fine-tune his vision over the course of a year.

“I think Midjourney knows me pretty intimately by now,” he jokes, reflecting on the iterative process of rendering visuals.

The result was a 75-minute feature where 95% of the content was AI-generated, produced at less than 15% of the cost of a standard Bollywood film.

The success of Naisha went beyond the screen; the titular digital heroine even secured an endorsement deal with a Hyderabad-based jewellery brand.

This shift allows creators to maintain total autonomy over their narratives.

Anchalia asks:

“Why wait for a studio’s approval if AI can allow me to make the movie on my own terms?”

He argues that the technology has effectively democratised the industry, allowing any young filmmaker with limited resources to produce a movie.

This sentiment is echoed by Arun Chandu, who directed a sci-fi satire, Gaganachari, on a budget of 20 million Indian rupees.

Chandu points out that this is “less than the cost of an Indian wedding”.

By using tools like Stable Diffusion and Photoshop, he was able to create complex military sequences that would have otherwise been financially impossible.

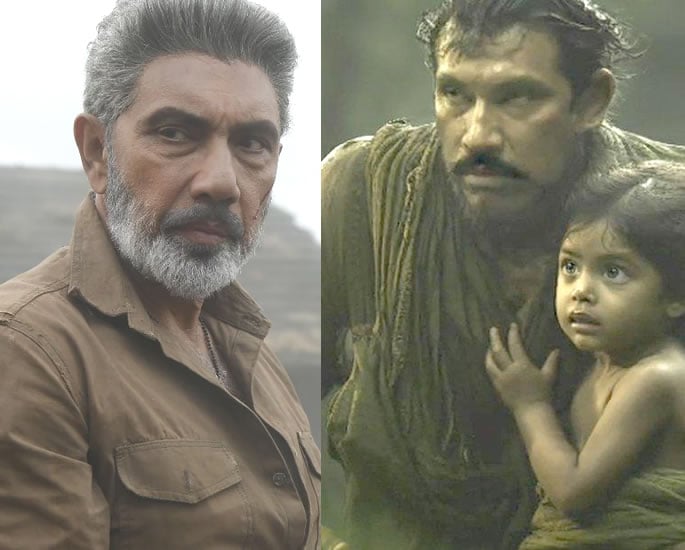

De-ageing Icons and the Digital Afterlife

While independent creators use AI for survival, big-budget productions use it for spectacle and nostalgia.

Digital de-ageing has become a prominent fixture in Indian cinema, allowing veteran stars to reclaim their youth for pivotal roles.

In the 2025 Malayalam thriller Rekhachithram, a 73-year-old Mammootty was transformed into a 30-something version of himself.

Andrew Jacob D’Crus of Mindstein Studios led this process, initially feeding the AI data from Mammootty’s 1985 film Kathodu Kathoram.

When the initial results appeared grainy, the team pivoted to 4K remastered footage from 1988’s Manu Uncle to achieve a seamless look.

The reception was overwhelmingly positive, with fans labelling it the best AI recreation in the history of the industry.

Veteran actor Sathyaraj, a household name following the Baahubali franchise, views this as a vital tool in a competitive market.

In 2024’s Weapon, he was de-aged from 70 to 30 for a scene.

Sathyaraj says: “If AI can extend my shelf-life by allowing me to play leading parts in action films, in an ageist industry such as ours, why not use it?”

Beyond de-ageing living legends, AI is also being used to resurrect deceased icons.

Director Srijit Mukherji utilised the technology to recreate the voices of Satyajit Ray and Uttam Kumar for his projects Padatik and Oti Uttam.

Mukherji believes that by involving the families of the deceased, the ethical hurdles are cleared. He views AI not as a threat, but as a masterable tool, stating:

“It isn’t an android-like monster trying to gobble up your creativity. It is aiding creativity, not replacing it.”

Cultural Challenges

Despite the efficiency gains, AI often stumbles when faced with India’s deep cultural and linguistic diversity.

Director Guhan Senniappan discovered these limitations while working on Weapon. He noted that AI models, largely trained on Western datasets, are frequently “tone-deaf” to Indian aesthetics.

When he prompted the technology for “demigod” imagery, the results were unrecognisable and lacked the hyperlocal references rooted in Indian mythology.

Senniappan continues to hire traditional storyboard artists for culturally rich scenes, arguing that “you would need to feed it the cultural memory of the original script”.

Linguistic nuances also present a significant hurdle.

In the 2023 Kannada film Ghost, director MG Srinivas used AI to clone the voice of lead star Shiva Rajkumar for multi-language releases.

However, the technology required human intervention to correct regional phonetic models and speech inconsistencies like lisps.

Furthermore, there is the issue of “hallucination” – where AI adds details that distort the original intent.

Aniket Bera of Purdue University’s Ideas Lab observed this while restoring 19th-century Indian film fragments.

He found that AI often “improved” scenes by softening shadows and contrasts that were central to the original mood.

Bera warns: “AI doesn’t understand symbolism, it only guesses patterns.”

Without constant human review, he fears the technology risks rewriting history by changing the visual language of classic cinema.

Ethical Problems

The rapid integration of AI has outpaced the Indian legal system, leaving filmmakers and performers in a vulnerable position.

Unlike the structured protections sought by Hollywood guilds, India lacks a comprehensive statute to safeguard against AI misuse.

Anamika Jha, a media entertainment lawyer, points out that while living persons have some likeness protections, these do not clearly extend to AI-generated imitations.

Jha explains: “The absence of explicit legislative reforms to address such uses proves that the law is not moving at the same speed as AI.”

This legal vacuum extends to posthumous rights; an actor’s voice or image could technically be used after death without formal consent, as these rights are not yet formally recognised in India.

The potential for creative overreach was highlighted by the 2025 re-release of the 2013 film Raanjhanaa.

AI was used to rewrite the original tragic ending into a happy one, reportedly without the consent of director Aanand L Rai.

This move sparked concerns about the integrity of human authorship.

Director Shekhar Kapur has been a vocal sceptic, noting that AI “cannot create mystery, feel fear or love”.

Even those who use the technology, like Arun Chandu, acknowledge its limitations.

Chandu now teaches a university course where he asks students to compare AI-made films with traditional ones.

He observes that while AI is faster, “the version that is more nuanced is always human”.

Indian cinema’s trajectory suggests that AI is no longer an optional novelty but a fundamental component of the filmmaking toolkit.

From the sound design studios where Sankaran AS and KC Sidharthan use AI-powered tools like Soundly to “do it ASAP”, to the pre-visualisation workflows of directors like Jithin Laal, the technology is undeniably enhancing productivity.

Laal now tests complex scenes using AI before committing financial resources to full-scale production, a move that reduces risk in an increasingly expensive industry.

The future of Indian cinema will likely be defined by how well it balances this newfound efficiency with the irreplaceable depth of human intuition.

While AI can process data and predict patterns, it remains a tool that requires a human hand to guide its cultural and emotional output.

As the industry navigates the lack of statutory frameworks and the technical “uncanny valley”, the consensus among many creators is one of cautious optimism.

Mastering these tools may be the only way for the next generation of storytellers to ensure that their voices, and the rich cultural heritage of Indian film, remain central to the cinematic experience.