Despite most of its apparel consisting of t-shirts, hoodies and oddities like a branded brick, the brand possesses a cult following.

Nike, Adidas, Ellesse…many South Asians will remember themselves or their parents wearing these streetwear fashion labels in the 1990s and early 2000s.

While these labels often attracted ridicule or stereotyping when worn by South Asians and other ethnic minorities, we are seeing the rise of streetwear fashion as just fashion.

Thanks to its current profitability, high fashion brands are adopting streetwear styles in their collection. While on the high street, the same styles are trickling down for the general public too.

We’re currently seeing this increased popularity among South Asians. But because of streetwear fashion’s counterculture and community beginnings, we explore how there’s more to this than money.

The Beginnings of Streetwear Fashion

Similar to Asian fashion, location plays an important in understanding streetwear’s roots.

Many recognise 1980s California as the start. This includes writer, designer and now documentary-maker, Bobby Hundreds, of 2017’s Built To Fail, one of the first streetwear documentaries.

Originally a surfwear and skater brand, California’s Stüssy merged performance-friendly clothing and hip-hop influences. Emblazoned with their hand-drawn logo, founder Shawn Stüssy helped coin the streetwear aesthetic as we know it.

With co-founder Frank Sinatra Jnr., Stüssy brought the label to New York. Thanks to the now iconic Union NYC shop, Stüssy grew in popularity.

Naturally, New York is an essential part of streetwear fashion’s story with its hip-hop roots. But other key sites include London, Miami and Tokyo where the story of streetwear continues today.

What is Streetwear Fashion?

Surprisingly, streetwear fashion is still hard to define in words. It encompasses everything from trainers to tracksuits, sliders to shorts.

Instead, it’s a look that is more instinctive both in how individuals put garments together and others recognise the style.

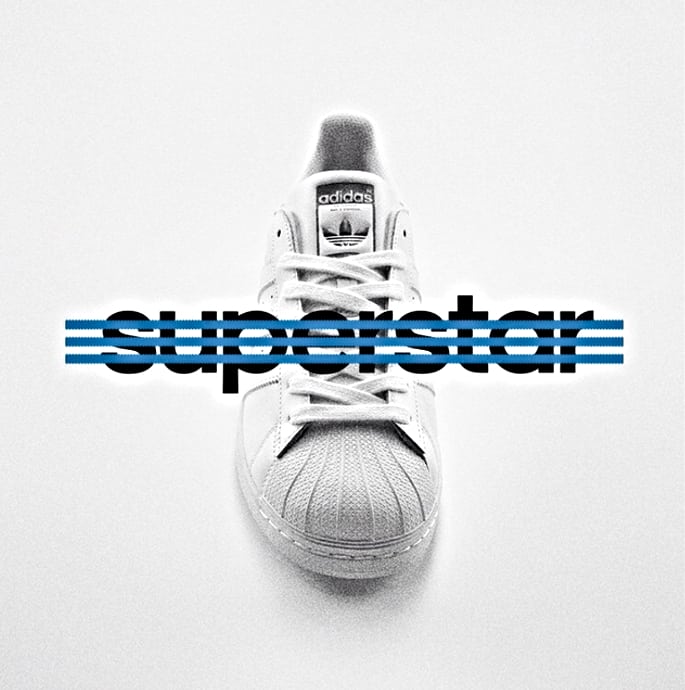

Indeed, streetwear often seems to have its own language like garms (garments) and kicks (yet another name for trainers). Plus all the references to specific styles as ‘Superstars’ to the Adidas Originals Superstar low-top trainers from 1969.

As per its history, streetwear is almost a catch-all terms for sportswear, skater and surf culture. It merges both high luxury and everyday fashions, taking influence from music and art.

Perhaps because of its associations with such subcultures, it’s a highly male-dominated section of the fashion industry. British fashion designer Nazir Mazhar, Russian designer Gosha Rubchinskiy and Supreme founder, James Jebbia are some of the biggest names in the sector.

Yet, streetwear’s profitability means that many high fashion houses are cashing in on streetwear’s appeal.

Authenticity versus Profit

Generally, streetwear companies are making money to rival huge fashion names too.

In 2017, estimated valuations of streetwear brand Supreme put its company at $1 billion. Despite most of its apparel consisting of t-shirts, hoodies and oddities like a branded brick, the brand possesses a cult following.

Because of its clever business model of a low supply for an ever-increasing demand, the high prices multiply extortionately for resellers on sites like eBay.

Of course, some of Supreme’s street credentials comes from this scarcity. Not to mention the fact that its founder, James Jebbia is also the founder of the aforementioned Union NYC shop.

However, the brand is at risk of losing its cool owing to its increasing elitism. In 2000, French high fashion brand, Louis Vuitton sent Supreme cease-and-desist letters for its use of an LV-inspired logo. Whereas in 2017, the two collaborated to sell apparel at eye-twitchingly high prices.

Nevertheless, one issue of high fashion’s appropriation of streetwear is the ease of rejecting the style at their convenience.

Spanish fashion house, Balenciaga profits off its adoption of streetwear collections for an attention-grabbing marketing strategy. The fashion label is so well known for this adoption that it’s hilariously spawned a pet ‘streetwear’ trademark, Pawlenciaga.

But already for its Spring/Summer 2019 collection, creative director Demna Gvasalia has left streetwear in the dust.

In comparison, one sector always remains loyal to streetwear and looks as if it will continue to do so regardless of profit.

Hip Hop Culture

In the classic chicken-and-egg debate, fashion always influences music and vice-versa.

Hip hop now dominates the US music scene, pushing out genres like rock music. Thanks to the ‘Americanisation’ of the Western world, if not beyond, this has a knock-on effect globally.

Though, this isn’t just spreading the genre’s sound but its style. After all, a huge part of hip hop is its fashion aesthetic.

Within a few years of release, over 75% of NBA players wore the aforementioned Adidas Originals Superstar trainers. But in the 2015 documentary, Just for Kicks, Run-DMC member. Darryl McDaniels, shares the story behind their song ‘My Adidas’.

The song originally was to encourage young people to stop imitating the stylings of prison inmates. However, it ultimately led to a $1 million endorsement deal between Adidas and the hip hop group.

An example of this connection today is American rapper Kanye West. He has turned his hand to clothing for a more successful second time with the brand, Yeezy.

After numerous sneaker collaborations with Nike, then Adidas, West’s Fall 2015 ready-to-wear collection met with positive reviews. Now, the American is allegedly a billionaire because of the company’s projected valuation.

Furthermore, as the increase in digital sales results in hip hop music’s dominance, it’s done the same for streetwear.

Streetwear Fashion in a Digital World

First, there’s the good of streetwear’s strong presence in the online space.

Fans of streetwear are some of the most passionate online with Facebook and Instagram communities like The Basement. This group boast 78 000 members, slightly less on its page and 274 000 Instagram followers.

The internet makes it easier for these fans to share their passion and form a real community spirit.

On the other hand, there’s the argument that the digital age has led to the homogenisation of fashion, including streetwear.

E-commerce makes it easier to access the same fashion brands with the click of a button. Even in countries that are thousands of miles apart, two people can be buying from the same brand or influencer.

Indeed, the rise of fashion bloggers or influencers from Instagram is equally complex. They can show off a unique creative flair to serve as sources of inspiration for followers.

Even their presence at fashion weeks and growing importance in the industry mean that fashion magazines aren’t the gatekeepers into this elite world anymore.

Conversely, perhaps this leads to the tactics of brands like Balenciaga. By putting out items like crocs, it can seem that there’s more pressure to create showy and click-bait collections.

Streetwear Fashion with Race and Class

In some respects, it’s problematic that high fashion houses can profit off the appeal of streetwear. As discussed, high fashion will pick up and reject streetwear as convenient.

Yet, there’s even more to the debate around streetwear fashion entering mainstream fashion.

In an interview, Nazir Mazhar points out how fashion houses like Givenchy sell streetwear items like tracksuits and t-shirts but won’t use this label.

Rather Givenchy dubs these items as its “commercial collection” while claiming that the 65-year-old Parisian fashion house has streetwear in its DNA.

Even Mazhar rejects the term streetwear for his clothing line. He critiques that his use of non-white models means that streetwear replaces fashion in descriptions of his work.

Essentially, it appears that ‘streetwear’, like ‘urban’, can be a code word for non-white and working class, even ‘chavvish’. Conversely, when a non-white person wears streetwear for a fashion house, it’s high fashion.

Naturally, this degree of snobbery from some can frustrating, but high fashion is often cyclical. Ultimately, even if high fashion’s interest fades, streetwear should endure.

Mazhar has a number of celebrity followers like Rihanna, Skepta and Tinashe and a long-time relationship with grime. He often collaborates with grime artists to design for them or see them walk in his shows.

Of course, there will continue to be brands like Supreme, selling streetwear at extortionate prices for rich kids to show off on Instagram.

However, like grime, streetwear continues to make room for creativity, independence and diversity to continue.

Like Mazhar, you don’t need a fashion degree to design streetwear, or like some streetwear enthusiasts, extreme wealth to buy pieces.

Instead, at the heart of streetwear style is independent talent and labels while mixing influences or high and low fashion.

South Asians and Streetwear Fashion

As mentioned, men are usually the face of streetwear fashion. But as model and writer, Simran Randhawa points out, increasingly women are gaining a platform. She cites independent brands and sellers like Lapp, Pam Pam and Jehu-Cal.

Then, Danish designer Astrid Andersen’s eponymous brand “fuses the worlds of luxury and sports”. While it still remains accessible for the average consumer with her Topshop collaboration selling out in record time.

Similarly, while the black community’s influence must receive credit, British Asians are creating fusion styles between streetwear and Desi fashions.

There’s the feminist apparel brand, Good Girl Gang. Then Seek Refuge is a modest streetwear label to empower women and represent Muslims.

Elsewhere, co-founders and brothers, Tanmit and Sunmit Singh founded Rootsgear Clothing Co. It began in 2004 in response to their experiences as Sikhs in post 9/11 America.

Now a global brand reaching UK audiences, it blends Punjabi heritage and streetwear style. Additionally, it collaborates with singers like Raxstar and sells merchandise from rappers Fateh Doe and Raja Kumari.

But this can be seen in stylish young South Asians like the model, Neelam Gill or the aforementioned, Simran Randhawa.

Randhawa has teamed up with Stella McCartney to celebrate the new Loop Sneaker collection – one of the first almost fully-recyclable sneakers ever.

As for young British Asian men, just look at the style of YouTuber Sangiev Sriskumar.

Although, streetwear influencers aren’t only the younger generation. Journalist, brand consultant and Soho Radio Presenter, Kish Kash is another streetwear aficionado, notable for his love of sneakers.

In comparison to the diaspora, streetwear hasn’t found its feet in India according to Indian fashion influencer, Keshav.

Community and Streetwear Fashion

Nevertheless, perhaps streetwear doesn’t need to have the same following in South Asia like the diaspora.

Streetwear emerged from countercultures of skating and surfing to become synonymous with much-misunderstood hip hop culture. The style has links with the racial and class subordination of ethnic minorities including the black and Latino communities.

But, while streetwear may continue to provoke negative stereotyping, South Asians and other communities can still use it for positive effect.

Streetwear is simply comfortable and a great look, playing a part of Asian club culture in the 1980s and 1990s.

After all, even Bend It Like Beckham made note of British Asian grandmothers’ love of pairing traditional Punjabi suits with trainers.

In a similar vein today, young South Asians in the diaspora seem to be using it as a way to rebel and build a community in the Western world.

Whether it’s fusing Desi style with streetwear or enthusing over Supreme’s next collection, there’s plenty to love about streetwear for British Asians.

Streetwear fashion is more than a style, but a whole culture. Of course, belonging to a culture is familiar to many South Asians.