"Can you imagine wearing a dupatta with jeans and a top? You look like a pehndu."

The dupatta, a long, flowing scarf, with decorative borders.

Made from bundles of threads, all woven together, the dupatta is an integral part of the culturally fixed Asian dress code, the shalwar kameez.

Dating back to the early traditions, it was used as a covering throne for the South Asian woman. Worn over both shoulders and the head. With an emphasis on covering the chest, the dupatta made women feel protected from the opposite gender.

As much as the cloth covered, it also stood as a symbol of modesty, dignity, and respect. Especially when amongst the elders, or while attending faith related ceremonies.

Many British Asian women grew up watching their mothers, sophisticatedly draped in the lengthy cultural tool. As a result, the dupatta was passed down to the next generation. But, through the westernised upbringing, has its cultural symbolism survived?

DESIblitz speaks to British Asian females, from all walks of life, to explore the impression the dupatta communicates today.

Dupatta in the British Asian Society

![]()

The early immigrants strongly represented their cultural identity, by strictly following their South Asian dress code. As such, the long flying in the air fabric differentiated women from those belonging to western society.

The dupatta culture was embedded and passed on through childhood memories:

“I and my sister loved playing with our Ammi’s dupattas. We felt more feminine, pretending to be brides.”

The first generation of British Asian women traditionally adapted the dupatta:

“Our mother always told us that your dupatta is your sharam* and haya*. Of which, is the izzat* of your household. Then with time, we realised how incomplete and naked we are without one,” says Sabiha, a 35 years old British Asian housewife.

Anisa, a working woman says:

“I wear a dupatta to the office with my trousers and shirt. It’s usually a mid length shawl or a scarf. As a Punjabi, it’s my national identity. I wear it around the shoulders and chest..”

Sabiha’s and Anisa’s comments touch upon individuality, nationalism and respectability.

Meanwhile, the second generation interprets the dupatta differently. Nazia, a college student says:

“Can you imagine wearing a dupatta with jeans and a top? You look like a pehndu*. It’s almost like pairing trainers with shalwar kameez. It ruins the outfit. But, if you wear Asian clothes, you automatically wear the dupatta that came with it.”

Whereas Saima, a university student says:

“I only wear it to cover deep necks or figure-hugging tops. Wrap a shawl around my neck in the winters. But, it is annoying to carry.”

Wearing a dupatta with western clothing is avoidable. Yet, with shalwar kameez, it is seen as a fixture. While for others, it is simply a hassle. However, for the modern yet traditional women, the dupatta has taken the form of a small scarf.

What does it mean to Wear or Not Wear the Dupatta?

![]()

Fashion studies have constantly conveyed that clothing communicates as a representative system of the individual look:

“Clothing is a language. And within every language of clothes, there are many different dialects and accents. Some almost unintelligible to members of the mainstream culture,” says Lurie Alison, an American novelist.

When we apply this to the Asian mentality, those who don’t carry the dupatta, are often perceived as dishonouring their culture. As Sabiha says:

“It’s an embarrassment seeing young girls at social family gatherings not wearing one. It looks shameless. Their parents have failed to introduce cultural values to them.”

On the other hand, those that wear the dupatta, are interpreted as belonging to a strict family. In addition, as ‘backwards’, being controlled by cultural traditions:

“At work, people often see me as very traditional. Sometimes they make me feel like I don’t fit in. Nevertheless, my dupatta offers a strange sense of freedom when moving around in different circles. It gives me control over my body,” says Anisa.

On the other hand, after having to explain what a dupatta is, a British Asian male, Tariq says:

“If they wear a dupatta, you immediately get a visual of their family background. Often the most well-mannered and reserved ladies.”

The Influence of the Fashion Industry on the Dupatta

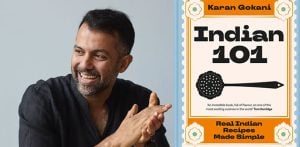

With the fast-paced fashion industry of India and Pakistan, the dupatta, which till now was in plain cotton colours, has evolved into glittering designs.

From nets and chiffons to finest silks, they are woven using intricate methods and techniques. With many hues, threads and embellishments, dupattas are prepared according to the wearer’s desire.

Yet, when it comes to the western fashion, tailored kurtas, tunics, gowns, and two-piece Asian attires, are dupattas beginning to fade? And thereby, have they merely become an occasional fashion statement?

For example, with the loose cut and digitised kurta designs, by designers like Khaadi, Sapphire and Beechtree, dupattas have become an unnecessary accessory. Further, with jacket style ensembles, this third piece looks out of place:

“They are definitely on their way out. Minus this third piece, she feels lighter and happier,” say designers Shantanu and Nikhil speaking to the Times of India.

Has High Fashion taken over the Cultural Traditions?

Then again, with the new avatars of the lengthy cloth, are some designers finding ways to work around the dupatta to maintain their modest grace?

For example, we have seen through Fashion Weeks of Pakistan and India, how it is clinched on one shoulder with an embellished waist belt. Distinguished designers like Payal Singhal, Sabyasachi Mukherjee and Elan, have all reinvented the dupatta fashion with this traditional twist.

Additionally, the long fabric has also taken the shape of a cape. Exceptional designers like Tarun Tahiliani and Shehla Chatoor have turned the long fabric into creative chic wings.

Clearly, the fashion professionals have used the cultural tool to create an intricate balance between tradition and modernity. To make sure the end creation is acceptable to the masses.

Be it a symbol of pride or a shield of honour and guardian of modesty, this accessory is much more than a long piece of cloth.

For the younger generation, this lengthy fabric is an unnecessary piece with no cultural implications. Simply, an irritation, restricting their movement. Or occasionally, a fashion statement, or a winter scarf.

Yet, for some British Asians, notably the older generation, the dupatta speaks of cultural values.

Accordingly, it has a unique language and an identity of its own.