"India did get freedom. They should have kept it together"

70 years on and the repercussions of Partition still trickle through the dense fields, deep rivers, and scorched earth of India and Pakistan.

The unified Indian subcontinent prior to the British Raj has become a distant memory. And as two nations attempt to acquire a strong global footing, both are fraught with sectarian violence on their borders and misconstrued lamentations regarding the other.

The generation of South Asians that witnessed Partition first-hand are now in the latter stage of their lives.

Despite the hardship, struggle and loss they endured, one cannot but help admire their keen resilience to resettle and rebuild in new and unfamiliar lands, and against all odds, start their lives once again.

But as their stories shift to other corners of the globe, memories of the past remain vivid and unyielding.

How vital is it for future generations to understand the history of their homelands, and for the stories of their parents and grandparents to be commemorated?

With the 70th anniversary of Partition approaching, Aidem Digital, the parent company of DESIblitz, will investigate the impact of Partition and Independence on Asians in Birmingham.

Through recorded video histories, written features, and a special exhibition supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF), we explore how such a seismic event in modern South Asian history continues to resonate even today.

DESIblitz begins with a historical retelling of Partition and Indian Independence.

A Setting Sun and a New Dawn

“At the stroke of the midnight hour, while the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom.” Jawaharlal Nehru in ‘Tryst with Destiny’ speech delivered on 14th August 1947.

Only two years on from a gruelling world war that would cripple some of the most powerful nations in the West, history was rewritten once again, this time in the exotic East.

It was on the night of 14th August when the glaring sun finally set on the once-invincible British Empire. India, described as the ‘Jewel in the Crown’ of Britain’s colonial conquest woke on 15th August to a hard-fought independence.

India was once again at liberty to govern itself, free of British control. But feelings of nationalist bliss soon dissipated once the reality of this new-found liberation set in.

The former glory and opulence of Mughal India had been pilfered and squandered by the reckless East India Company. A few centuries later, the British Raj had finally had its fun and left the vast country a shell of its former self.

But arguably more devastating to India’s citizens was the annexing of the country into two – India and Pakistan.

The road to Partition is one that has been hotly contested. Historians mostly agree that it was proposed after Indian independence or “swaraj” (self-rule) had been called for by the spiritual Indian leader Mahatma Mohandas Gandhi.

For many Indian revolutionaries following Gandhi, the oppressive British rule was no longer desired, particularly as it placed Indians as second-class citizens in their own homeland.

But India’s citizens only came to know of Partition on 3rd June 1947, via a live broadcast on All India Radio. The Viceroy of India, Mountbatten was joined by Jawaharlal Nehru (Congress Party Leader), Muhammad Ali Jinnah (Muslim League Leader), and Baldev Singh (representative of the Sikhs).

They each spoke of the decision to divide India into two, which included splitting up Punjab and Bengal. Strangely enough, none of these men appeared too enthusiastic about the vague plan for Independence that was intended to come into force before June 1948.

Birmingham resident, Muhammad Shafi was born in 1935 in the Punjabi village of Nakodar. He tells us that prior to talks of partition, his village lived in relative peace and harmony:

“Then there was a time when the election days came. That election was a kind of referendum. The Muslim League would say that we want Pakistan. Congress would argue that we would not let Pakistan be created.

“The British ruled the government of India. The British would say that this issue could not be resolved through fight and violence. And therefore hold a referendum amongst all the Muslims. The majority of people in areas of predominantly Muslim population who voted in favour would go to Pakistan. Those areas with little Muslim population would stay in India. There were many Muslims also with Congress.

“In our area of Nakodar, a referendum took place, where on our seat Wali Muhammad Gohir was Muslim League’s representative. And when the result came, Muslim League’s Wali Gohir won. Then a caretaker government was formed. The British managed to agree that yes we will do independence. But before Independence, a caretaker government will need to be formed.”

While the choice for a separate state had become unanimous, many of India’s citizens puzzled over their future – where exactly would this Pakistan be? After the Mountbatten plan had been announced, it was another month before imperial map maker Cyril Radcliffe first stepped foot into the country. Having never visited India before, he was charged with the arduous task of marking the final red line – deciding the fate of millions.

But Radcliffe only had six weeks to decide the border as the date of Independence was hastily moved forward by 10 months – to 15th August 1947.

Partition arrived as soon as Independence did, but the actual lines splitting the Punjab and Bengal provinces were only published two days later, on 17th August 1947. In both areas, Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs had no clue of whether they were on the right side of the border.

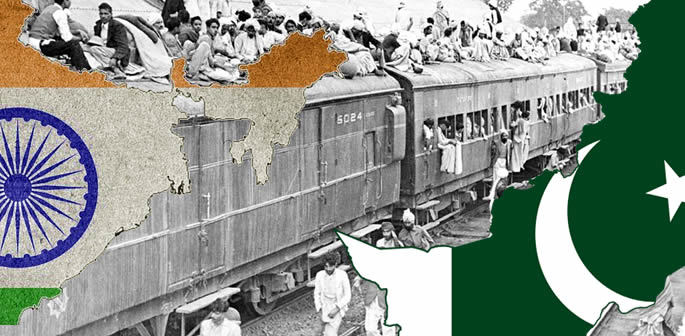

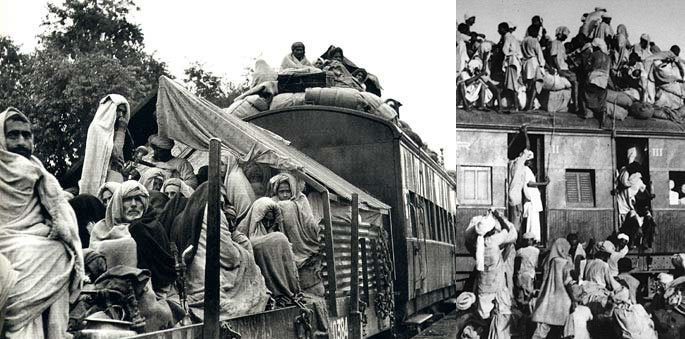

The confusion and uncertainty led to the mass migration of up to 12 million people. Their displacement came at a huge cost – between 500,000 and 1 million people died amidst unprecedented violence and brutality.

A Violent Reality

“Nations are born in the hearts of Poets, they prosper and die in the hands of Politicians.” Allama Muhammad Iqbal

Alex Von Tunzelmann in her book, Indian Summer: The Secret History of the End of an Empire, writes: “Violence was a much-predicted consequence of the handover, but preparations for dealing with it had been catastrophically inadequate.”

In a bid for their freedom, many of India’s most populous cities had been overcome with riots and destruction over the years. Mahatma Gandhi’s hopes for peaceful protests (satyagraha) had very quickly turned into something more deadly as British officers attempted to tame the growing crowds.

While sentiments against the British were to be expected, what was unfortunate was the rising divisions between Indian sects.

Gandhi, Nehru, and Jinnah were unsuccessful in calming the tensions – each being preoccupied with his own nationalist ideology. In the end, neither Nehru or Jinnah was completely happy with the idea of Partition. Gandhi, by this point, had completely washed his hands of the whole affair – believing that a divided India was the worst thing that could happen.

Of course, these thoughts ran down into the populous. Some believed that a different state was necessary to ensure equal rights for minorities, while others wished India would remain as one. On the whole, many citizens felt that their own needs were made secondary to their leader’s own desires:

“Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and Mr Jinnah cheated India. India did get freedom. They should have kept it together. Mr Jinnah wanted to be the Prime Minister. While Jawaharlal Nehru wanted to be Prime Minister as well. It is why Pakistan became an independent state.

“Mr Jinnah said I would take control of Pakistan. …Nehru was going to take care of India, regardless and not give us any rights. This is how two countries became a reality,” says Mohan Singh.

Pre-Independence, each community had largely been united against one common foe – the British. Once the British left India, however, they had only each other to war with.

Poverty, riots, and carnage filled the streets and alleyways of Punjab and Bengal following Partition. What should have been sentiments of relief and joy for Independence became a bloody battle for survival as the nation found itself brutally cleaved in two.

The deliberate withholding of the border lines by Mountbatten only incensed feelings of frustration and anger – how could people expect to pack up their entire lives and move elsewhere?

Fear of being found on the ‘enemy’ side mounted divisions between sects who once were neighbours. While in some of the narratives that we hear, many neighbours protected each other, in other instances they found themselves running from each other for survival.

Trains delivering families to either side of the border arrived filled with dead bodies. Parents were separated from their children, brothers from their sisters. Kidnapping, rape, looting and brutal killings were rampant.

Many refugee camps were built to accommodate those who had to forgo their homes and possessions. They spent months there before being moved on to the apparent safety of their new homeland.

To this day, Partition is remembered for the trauma and loss it caused for some 12 million displaced people and not the freedom it gave to 400 million. It is the memories of those who survived that we commemorate for future generations of Asians.

In our next article, DESIblitz will explore the trauma and loss faced by those Indians and Pakistanis who endured the brutality of 1947 Partition.