“What can I say we saw? Trains with killings. Children and women were being killed"

The memories of 1947 Partition are steeped in trauma and pain. Its horrors cling to the pages of unofficial death tolls, while the stench of murdered men, women, and children remain deeply entrenched within the fields and rivers of Punjab and Bengal.

British history books offer little detail on the reality of this brutal period. While most of us are familiar with the dates of Independence – 14th and 15th August – less is known about the personal loss and violent aftermath.

For a clearer picture of the horrors that many witnessed, we must seek out those who endured Partition first-hand. And saw the bloodshed through their own eyes.

Pieced together, these personal accounts and oral histories offer us a better understanding of the reality of August 1947 and the forced migration of 14 million citizens from one stretch of land to another.

Inter-community Conflict and Crossing Borders

By the summer of 1947, the British Empire’s ‘Divide and Rule’ effort had succeeded and their agenda rapidly transformed to ‘Divide and Quit’.

In the days leading up to Partition, worry and uncertainty set in. Citizens could foresee that Punjab and Bengal would suffer the greatest loss, as the borderline would split both regions in half. But where exactly would these borders be? And what did this new Pakistan look like?

Even 70 years later, when one thinks of Partition, horror, bloodshed and unabridged violence come to mind. Despite the centre points of the carnage being mostly in the east and west, its ripple effects reverberated throughout India.

Estimates of casualties vary wildly. Some historians believe that around 200,000 men, women and children were killed, while others insist that the death toll is closer to 1 million.

It is clear, however, that the violence did not begin once the official line had been drawn. In fact, inter-community skirmishes and rioting had already erupted in the major cities and in pocketed villages.

Since the British were no longer a dominating force, Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs had only their respective leaders to rely on for guidance. Something which ultimately Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Jawaharlal Nehru, Mahatma Gandhi and Tara Singh failed to enforce.

Bikram Singh Bhamra was born in 1929 in the Kapurthala state of Punjab. He recalls the rising violence that began to build once news of Pakistan had been officially announced.

A teenager at the time, Bikram admits that communal harmony did exist between the different faith groups. In fact, it was only after the likes of Jinnah and Nehru began to speak of division and separation that the robust bond between neighbours began to splinter and fragment:

“In [the] 40s, something, a wind of change happened and hatred started coming in by the speeches. Some of the leaders started giving speeches, inciting people against each other. In the beginning here and there, some fighting started coming up and then it went on increasing.”

With little understanding of the secret negotiations taking place between their great leaders in far-off Delhi, feelings of restlessness increased.

The communal rioting of the cities began to spread. Rumours and local gossip began to surface of not-so-distant murders taking place in cold blood. Stories of unexplained vanishings and single bodies discovered face down in nearby rivers.

“In Jalandhar, a Sikh was murdered and that’s where the hatred started more. It increased and increased and increased. But it wasn’t as much as I heard on the Pakistan side or the Lahore side of Punjab,” Bikram adds.

Gian Kaur, from Ludhiana, mentions how individual faith groups began to mass together. Safety came in numbers, and families became more guarded against strangers:

“I remember when on the first day all the noise and tension occurred. In our district, all the noise and tension first happened in Jagraon. My husband’s paternal uncle came to the city. People travel to the city from the villages for shopping. He was killed there. On the first day, he was killed.

“Then there was a lot of noise, tension and violence. Then people did a lot for their own safety. I was small. I remember on the rooftops we put rocks and stones. We were told not to hide. But in fact, hit any violent person with the stones and rocks.”

“In the night we would not put the lights on. Villages used diyas. We were not allowed to light the lanterns or diyas. If anyone saw a diya lit up, a Pakistan plane would hit that place with a bomb. In the villages, people would eat in the day and then go into their homes.”

For locals, sensitivities became ever more fragile, as distrust between villagers and townsfolk began to rapidly increase. It was this that led to groups on both sides deciding to take their livelihoods into their own hands.

Blood-soaked Trains and Cramped Refugee Camps

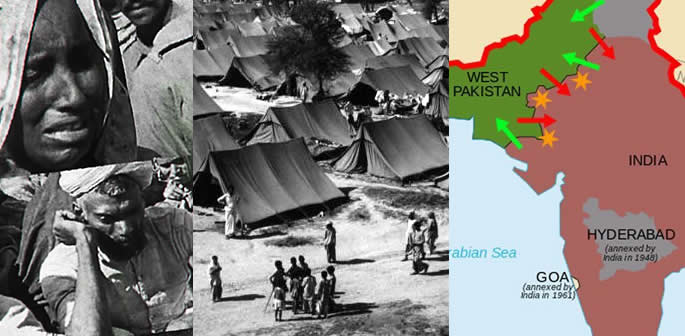

Needless to say, when the moment of Partition finally came, both India and Pakistan were ill-equipped to handle the 14 million refugees that migrated on both sides.

While many families across India decided to make their move in the weeks prior to 14th August, confusion around where the lines would exactly be meant that many Indians and Pakistanis (especially in Punjab and Bengal) were forced to wait until Independence arrived to decide on what to do next.

For some of these families, however, the decision was made for them.

70-year-old Riaz Farooq was only a baby at the time of Partition. Born in Jalandhar, he tells us that his family believed (according to radio news and the local papers) that their village would remain within the borders of Pakistan. However, once Independence came, the scenario proved to be very different indeed:

“14th of August came and went. The next day, in that area where they were living, they hard serious noises and screams on one end of that mahala where certain houses were put on fire and people were running around. That’s when they realised that something has happened.”

Under intense fear and worry of what might come if they remained where they were, Riaz’s grandfather and extended family decided to leave their haveli directly:

“They decided to leave the house within 10-15 minutes. It was kind of an abrupt decision and there was no choice for them, they left that house.

“So all women, children, older people… whatever they were wearing and whatever they could grab in the moment. Even the food that was being cooked on the stove, that was left and they got out of the door.”

Tarsem Singh who was only 11 years old at the time of Partition, explains: “When the fighting broke out, there was a group of Pakistanis near to us. Our daddy dropped the entire village to the camp in Phillaur.

“There was one elderly man in Kotli who could not walk and thus stayed in his house. A man hit him with a knife. In defence, another man said this was not good. He was an elderly man, so you should not have killed him.”

Refugee camps were set up near the major cities of Delhi and Lahore to accommodate the incoming families and offer them shelter.

Families travelled on foot or in carts through the rural fields of Punjab. Others, took special trains to transport them from Jalandhar and Amritsar to Lahore.

These refugee trains, however, proved to be a deadly means of transport, as whole carriages would arrive at their destination filled with fresh corpses.

As Charn Kaur says: “What can I say we saw? Trains with killings. Children and women were being killed. Atrocious acts and horrid violence towards them.”

Violence against women was particularly brutal. Sexual violence and rape plagued both sides. Some women took their own lives rather than be pillaged by strange men:

“It was awful… what was seen and witnessed. Now, if someone harmed your sister, surely you are going to feel pain, aren’t you? That’s the point.”

For those who did manage to arrive safely to the other side, they found themselves estranged from their family members. Refugee camps swelled with men, women and children, and life was both cramped and difficult.

The stifling heat of August meant that many of these camps became riddled with disease and infection.

Muhammad Shafi, born in Nakodar, was one of the many children of Partition who found themselves living in a refugee camp, awaiting the day his family would be given a new home:

“In that camp, we stayed for 3 months. We were hungry. Every day a camp of 200,000-300,000 was situated in the South. A camp of 100,000-200,000 was located towards the North. Everyday 100-200 people suffering from hunger and disease would die.

“Within 3 months, it became a very large graveyard. Some people didn’t even have cloth for the burials. My grandmother passed away there. There we dug some space and buried her.”

“We saw a lot of hunger and faced many hardships. In the many surrounding wells, not knowing the enemy who poisoned the water.. made it hard for us to fill up the water.”

Sardara Begum from Kotli, India adds: “Everyone was living in their houses peacefully, but then it all turned into chaos and turmoil. People from homes sneakily started to leave. With some heading for India, while others went towards Pakistan. People were killed in trains and cars, and houses set on fire.

“People feared for their lives and discreetly left. When hiding and leaving, I was young then… but I remember hiding and going through the crops to escape from the village.

“The killings were such that as you walked you saw dead bodies. This is how horrid the time was. Mothers running, who could not carry their children, were throwing them to the ground. That traumatic time was like the apocalypse.”

Oppression, disunity and a fear of the unknown can bring out the best in some individuals and the worst in others, and this was very much the case for 1947 Partition.

Despite the incensed tensions that existed between the faith groups, many families and communities united with their supposed ‘foes’ and helped to keep them safe.

Amrik Singh Purewal of Jalandhar explains that his father was the local village head and had a very different experience of Partition:

“The tensions occurred. The Muslims left Chakkan for Nakodar where their camp was set up. It was called ‘The Refugee Camp’. We would go there, and sometimes drop ration off to them.

“There was no violence. Everything happened peacefully.”

Mohan Singh was aged 10 during the upheaval and lived in the village of Moron Mandi near the town of Apra. He recalls:

“When the uproar started. In a village near us called Jagatpur, next to Makanpur, Muslims started to leave the village heading for Phillaur camp. I was young at the time, but I fully remember.

“As the Muslims went towards this camp, people on horses from other villages went after them to kill them. They turned up with swords and weapons to kill them.

“When they arrived at the boundary of our village all the people got together. They saved all the Muslims and brought them safely to our village and seated them.

“They served food and water to them as they were hungry. Then, the military from the Phillaur camp was called. They were all then safely escorted to the camp.

“Then when I was young, I went to Jalandhar. Near the stream, there was a very large Muslim camp. And that time it rained so heavily that Chaheru’s stream overflowed severely, destroying half the camp and killing many Muslims.

“The water dragged them and their dead bodies lay there. It was terrible how those poor people got killed. They were killed innocently.”

Remembering 1947 Partition Today

70 years on and the memories of childhood remain fresh in the minds of many of these elderly Indians and Pakistanis, now in their 80s and 90s.

Families were torn asunder in the chaos of August 1947. Blood, violence and death followed refugees as they travelled on trains to escape their former homes. Even decades later, some will maintain their silence and speak very little about the horrors that they witnessed.

For the preservation of South Asian history, however, remembrance of this pivotal period is vital for future generations.

In recent times, this critical event has been revisited through different mediums, including literature and film. The prolific South Asian writer, Saadat Hasan Manto is perhaps one of the most celebrated storytellers of India’s Independence.

Although he died in 1955, Manto’s short stories continue to resonate with readers due to their daring and honest portrayal. Novellas like Toba Tek Singh and Mottled Dawn recall the intense brutality that came from communities turning against each other.

Train to Pakistan is another historical novel by Khushwant Singh, that exposes the torture and rape of women on both sides.

TV adaptations and films have also attempted to bring light to some of these personal accounts. For instance, Daastan (The Tale), adapted from Razia Butt’s novel, Bano, and Gurinder Chadha’s Viceroy’s House.

What is perhaps most intriguing about 1947 Partition is that although it only directly affected a section of the Indian population – those living near the borders – the tremors could be felt by all.

Even today, they still echo between the two nations of India and Pakistan. However, the trauma, pain and loss that was felt by so many enabled a new beginning for both these countries. And if these personal histories tell us anything, they teach us that the sacrifices of our forefathers were not made in vain.

In our next article, DESIblitz will explore the role of women and the brutality that they endured during 1947 Partition.