"I think it is very important to be clear about where we stand"

Amrit Wilson’s seminal work, Finding A Voice was first published in 1978 and is revolutionary for interviewing South Asian working-class women in Britain.

However, readers can enjoy this evergreen landmark book even in the 21st century.

Despite Virago Press being the original publishers, Daraja Press has republished Finding A Voice by Amrit Wilson with a special touch.

Through a series of interviews in languages including Hindi, Urdu and Bengali, real British Asian women examined their own lives.

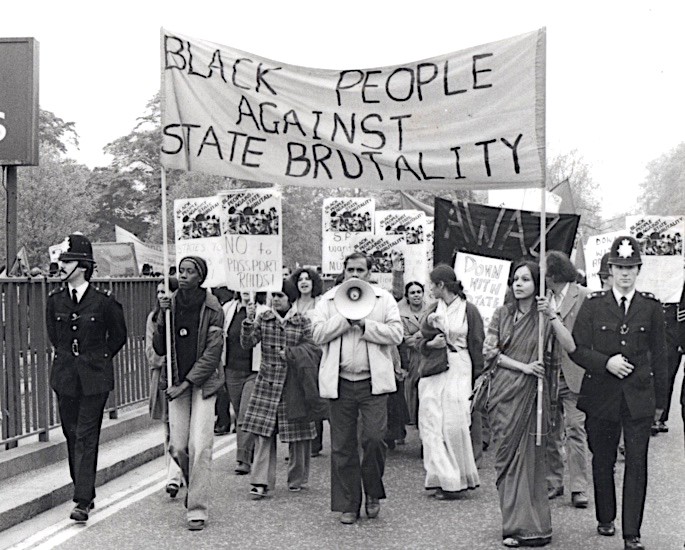

The women shared their attitudes toward love and marriages, along with family relationships and friendships. Having said that, the book also shows a forgotten side of history like working-class struggles in the 1970s.

Courtesy of Wilson, we gain the rare opportunity to hear the perspective of British Asian women of that particular era. This includes the brave women who participated in strikes such as the one at the Grunwick photo processing plant.

Amrit’s interviewees additionally recount experiences of racism in housing, education and from the law.

In fact, the new edition of Finding A Voice includes another chapter, ‘Reflecting on Finding a Voice in 2018.’

Young British Asian women explore what the book means to them. They consider in what ways their lives are different and similar to Wilson’s original interviewees.

In this process, they discuss topics like racism and the fight for justice at Yarlswood detention centre.

Yet, they also consider personal life such as the complexity of mother-daughter relationships in South Asian families.

DESIblitz chats to the author following her successful book launch at Birmingham’s Meena Centre on Saturday, December 7, 2018.

Discover thoughts of Amrit Wilson on interviewing, activism and why 2018 was the right time to republish Finding A Voice.

The Inspiration Behind Writing Finding A Voice

Amrit Wilson had many sources of inspiration when writing Finding A Voice.

In a sound recording published on the British Library website, she recalls meeting a woman on her travels in London. While asking for directions, she discovered more about the woman’s personal story and was inspired to carry this on.

Amrit reveals to DESblitz that her inspiration for writing Finding A Voice “was the real experiences of Asian women, their ideas, feelings and stories.”

Wilson adds:

“In the late 70s, our communities were being seen through a very colonial anthropological lens. A growing number of academics were becoming ‘experts’ by studying and objectifying us.

“They would gather material by meeting Asian women, and speaking to them, often via their husbands, and then come up with theories which were implicitly racist – that Asian women were ‘passive’, for example, or to that we have low ‘pain thresholds’, poor mothering skills and so on.

“What was worse was that often these stereotypes were used to justify government policies.”

“My approach was the opposite. I knew that women thought about, and reflected on, their lives and that they had a lot to say – that was ultimately my inspiration.”

It is heartening to hear that Amrit treated British Asian women with the respect they deserve. It seems obvious that the best people to speak on the British Asian female experience was the women themselves.

Nevertheless, sometimes the seemingly obvious needs reiterating. In fact, we asked Amrit Wilson on what was important to know when interviewing and writing personal stories.

She responds:

“I think the most important thing is to give people space and respect and to have empathy to understand what they are saying and, as one of today’s young writers has put it in the new version of Finding A Voice, it is important to listen to ‘the story that sits between the words.’”

It is precisely this ability to listen and help interviewees feel at ease that makes Finding A Voice so special.

British Asian women in younger generations have relatively little opportunities to tell their stories – never mind in older generations.

Why Republish Finding A Voice?

The collection’s powerful and diverse stories is a real strength of Finding A Voice. Unsurprisingly, Amrit Wilson did get to know her interviewees quite well as she reveals:

“I still keep in touch with them. Some sadly have passed away, a few are reluctant to think about those difficult days while others are still strong and hopeful about the future.”

Actually, this forms some of the basis for republishing Finding A Voice now.

Wilson initially explains:

“There were two main reasons why this book is of interest now. Firstly, because this is our history in this country, without history we are rootless, we cannot really make sense of the present, or shape the future.”

Secondly, she shares her insight into why Finding A Voice is as timely as ever:

“Secondly, because, while what women faced back in the late seventies may have changed, that harsh patriarchy, or sometimes the shadows of that harsh patriarchy, still remain as shadows in our lives or sometimes in starker forms.”

There is still a debate as to whether it has become easier or not for British Asian women to share their stories. Amrit weighs this up, stating:

“I think that depends on class and age and other factors. Also, many women still do not wish to reveal their stories if it shows their loved ones in a bad light – or even places themselves in a dangerous situation.

“This was true when I wrote my book too and this is why I changed the names of many of the women.”

Activism and Technology

It is equally important to consider other changes such as modern tools for activism.

Increasingly activists connect online to form communities for support or action. Whereas Finding A Voice became highly influential for its time as literature was one of the few available options.

Sharing her perspective on this, Wilson says:

“I think with social media, books are less used by activists.”

“The internet provides us quickly with small parcels of information.

“But this can have its problems too because it means that people do not gain the type of nuance or depth of understanding or analysis which they would have from books.

“And I think in this internet age, activists are increasingly realising this.”

She continues, reflecting on Finding A Voice:

“Of course, books like mine which are very readable have had an appeal in the past.

“In fact, last month at the London launch of the book, I was very touched to hear Meera Syal remembering the three things which had affected and strengthened her most.

“The first was the strike of Asian women at the Grunwick factory, the second was the Southhall resistance against the National Front when the whole community came out and the third was my book – Finding A Voice.”

Activism in the 21st Century

Similarly, we need to consider the language of activism in contemporary times. During her book launch at Birmingham’s Meena Centre, Wilson convincingly discussed the idea of losing labels like ‘feminist’ for ideas.

Alternatively, she expresses how buzzwords like ‘decolonisation’ can become confusing.

This fascinating discussion did raise the question of changing how we use language in activism, with Wilson elaborating:

“Yes, I think it is very important to be clear about where we stand, If we see ourselves as feminists, for example, it is important to think about where we stand in terms of our approach to race, class, caste and so on.

“Otherwise enormous misunderstandings can build up.”

The launch of Finding A Voice was particularly enjoyable as it offered the chance for a Questions and Answer session with Amrit. Through this, several interesting topics of discussion emerged.

This includes different ideas on how to approach activism between generations. Arguably, the younger generation of activists emphasises the importance of self-care in addition to resistance.

Wilson shares her thoughts on striking this careful balance:

“Patriarchy places all caring duties on the shoulders of women and as a result, we are socialised into not thinking or caring for ourselves – self-care is therefore very important.

“But resistance is equally important at a time when misogyny, racism and Islamophobia are rampant.”

“When people are being deported after spending their life time in this country, for example, or when the Far Right is on the rise and our younger brothers and sisters, our children, are facing horrific attacks in school.

“Or, indeed, when women’s refuges and shelters built up over the last three decades are being closed down so that those who face domestic violence have nowhere to turn to.”

Further commenting, she mentions:

“But when we resist we must also care for those who are resisting with us so that self-care becomes a collective self-care, given with love and friendship.”

Fighting For A Better Future

After such a long career in activism and writing, Amrit Wilson draws on her personal experiences that the younger generation can benefit from.

She has a few additional words of wisdom for the younger generation:

“I am excited by their energy and desire for change.”

“I would suggest though that they look at the history of their own communities – it would strengthen them and perhaps give them new ideas and help open a dialogue which can only be positive for everyone.”

She is equally hopeful for the future. When imagining another 40 years in the future, she hopes:

“My dream is the same as that of so many other women – of a world without war and inequality, where we are free to live in peace and happiness and fulfil our true potential.

“I don’t know whether it will happen in 40 years, if not people will still struggle and hope and long for it.”

Regardless of whether this happens or not, Finding A Voice is certain to remain an influential book.

The powerful book has won the Martin Luther King Memorial Prize.

Over the past 40 years, it has helped many generations of activists in the struggle for equality. The addition of a new preface and chapter ensures its relevance to today’s fractious society.

Republished on October 1, 2018, Finding A Voice is available to purchase on Amazon and Daraja Press.