‘Doll Face’ is a "British Asian girl but she would never describe herself as that.”

British Asian actress, Karen Mann unapologetically discusses pre-marital sex and abortion in her self-penned play, Doll Face.

Doll Face crucially examines the oft-ignored British Asian female experience beyond worn-out stereotypes for the Camden Fringe Festival 2018.

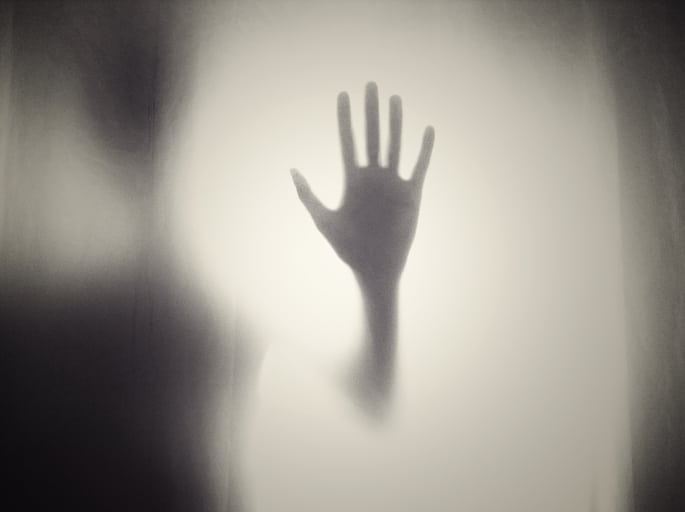

Therefore, this new play follows the character of ‘Doll Face’ as she waits in an abortion clinic.

After seeking to escape reality with alcohol, drugs and lust, we witness her reflecting on the past. But now, she has to face up to her conflicting desires as a British Asian woman to move forward.

Mann refuses to keep silent about the topic of sex and other cultural taboos.

Doll Face plays a key part in her aims to start self-reflective conversations in the Asian community and beyond.

From writing Doll Face out of frustration with the British society’s attitudes to Asians on screen and off, DESIblitz talks to Karen Mann about the play and her new collective for South Asian creatives, SHADES.

The Story of Doll Face

A solo show with Karen Mann as the writer and principal actress, ‘Doll Face’ is a “British Asian girl but she would never describe herself as that.”

Originally from Birmingham, Mann experiences the conflict of growing up in two cultures and channels this into imagining:

“What happens when you have to lie a lot and when you try to mould yourself into the perfect person on both sides.”

In fact, Doll Face immediately grapples with the consequences of wanting “to be a good Indian girl, the perfect daughter”.

The performance simultaneously questions how this can balance with the allure of Western “freedom” and fitting in with her friends.

We open with ‘Doll Face’ praying and discover that she’s in an abortion clinic due to self-denial.

Despite reaching 23 weeks, she can’t comprehend pregnancy because of her quest for perfection.

Instead, our protagonist falls to prayer and wishful thinking, even seeing the abortion as an opportunity to ‘start again’.

Nonetheless, Karen Mann emphasises that ‘Doll Face’ ultimately realises there will always be a clash between her two cultures.

While describing the play as “hopeful”, Mann explains how it highlights the mental health consequences of such inner torment.

But, she sees artistic work like Doll Face as a chance to start an intergenerational dialogue on tricky topics:

“Maybe if my generation understands that we just need to open up the conversation – not in a way like this is right or wrong – our parents might be able to talk to us and understand our point of view instead of hiding.”

Premarital sex is definitely one of the topics that British Asians need to address. Karen Mann points out the potential backlash of even talking about the subject, yet doesn’t let this stop her:

“That was the thing, I was so fed up. I was like no, this is someone’s story and everyone can relate to it at certain points and certain ways. And our parents aren’t stupid, they know what we do, even if they don’t admit to it.”

Creating a play like Doll Face is certainly one way of putting British Asian issues front-and-centre. Even the most conservative of parents can’t hide from it.

However, in spite of such a weighty subject matter, the play’s optimistic outlook clearly contributes to its success.

Turning Her Hand to Writing

Karen Mann is a highly-trained actor, attending prestigious schools and acts under the name Freida Mann.

Conversely, she’s a newcomer to putting pen to paper, and deliberately avoiding writing guides.

Preferring feedback from friends and family, she drew on her experiences and those of others to write Doll Face. She tells us:

“Originally, it was a story of three generations: the grandmother, mother and the daughter now.”

“I kept trying to write it and in my head, I was like: ‘I can’t work this out, because I’m an actor first, not a writer. I don’t get it.'”

However, she counts herself “lucky” that the Arcola Theatre then supported her in the research and development of the piece, to great effect:

“I got 10 women in from different backgrounds. It was predominately South Asian, but I really wanted other people’s experiences to see how much we can relate. And I was so shocked by how much we all related.”

She adds:

“It was so nice, it was like therapy. I’ve never been so open with people and they were so open with me.”

“And that’s when I realised, this story has to be growing up as a female and all the things that are put on us. We’re brought up with so much baggage.”

In fact, it appears that Doll Face is Mann’s way of making a visible change rather than remaining passively critical:

“I used to look at our culture and think: ‘that’s shit, that’s shit…” But I could never put anything to it. I couldn’t say this is why it’s wrong and this is why it’s like that.'”

It was only after the research and development session that she realised:

“I knew I needed to write this story. I needed to write a woman’s story because our stories aren’t told.”

She continues:

“If they are told, we’re always victims. Or when you watch drama series, we’re terrorists or our parents are forcing us to get married.”

“I was like: that is someone’s story, I completely get that. But what about the other side of us?”

“Because there’s so many of us who have grown up in multicultural places and that’s not our story. We’ve grown up, we’ve gone to uni, we’ve had boyfriends, we’ve done all of that, why aren’t we talking about those stories?”

Developing Doll Face with Music and Movement

Karen Mann initially performed Doll Face as a 10-minute scratch performance in early 2018.

However, she came to refine the dialogue-heavy first drafts of Doll Face for 2018’s Camden Fringe festival:

“I realised I can’t just talk and tell a story that we never tell and hope the audience will understand.”

Even in the last week of rehearsals before the show, Mann worked on this with her director, Anna Marshall and later, Natasha Kathi-Chandra.

To balance out Doll Face’s sex scenes and rape scene, they consider movement to be the perfect solution:

“We found it was a lot more powerful rather than saying it, because if you’re just watching what happens to someone, you are forced to watch it.”

“Whereas if you’re saying it, you remove yourself from it. It’s a really interesting device for me. I didn’t think I’d use movement as much as I did…”

The current version of Doll Face makes more use of music and dance than its predecessor. Nevertheless, Karen Mann makes several interesting stylistic choices in her revised version, using movement in another way.

She explains how there’s a “push-pull factor” in her performance of ‘Doll Face’:

“She’s forced into labour – but you’re there for hours and so it’s putting yourself in that mindset. If you’re put into labour, you don’t want to be in that room, you want to be anywhere else.”

Ultimately, the main character of ‘Doll Face’ seeks to escape from the room, using the movement of time:

“I’ll be talking to the audience and it would be getting up and doing that movement. It’s going back into time and seeing how she ended up there. So that’s how we worked with movement – going back and moving forward.”

Understanding Doll Face’s Audience

Not only does ‘Doll Face’ go back and forth to her past, in comparison to the feeling of entrapment in her present self, but the character notably has a Birmingham accent.

A marked contrast to the typical ‘theatre’ accent for audiences at the Camden Fringe.

Mann tells us the accent was a “natural” part of the role, but comments:

“It [the accent] wasn’t too strong. It was like: “is she from there, isn’t she from there?” It was something else that was different about her when you’re watching.”

While Mann loves a Brummie accent for its friendly tone, she admits to playing it down a lot:

“It was just that she’s an other in so many ways and everyone I know who’s got an accent, they hide it, especially in our industry.”

“If you’ve got a Brummie accent or a strong accent from Yorkshire or whatever, people think of you in a certain way, don’t they?”

“So she’s trying to escape all of that. It’s another layer of I’m brown, I’m female and I’ve got an accent. It’s all these things that you don’t even think about how it affects other people.”

Mann’s thought process behind Doll Face is equally as fascinating as the onstage action.

It’s interesting to see the parallels between how the playwright chooses to compromise in order to keep her audience onside.

Nevertheless, Mann is resolute to avoid portraying ‘Doll Face’ as a victim despite prior feedback to do so.

This is clearly the right choice, particularly for the Camden Fringe. In addition to encouragement to develop it longer than its 45 minute running time, feedback is positive:

“I definitely wanted a lot of South Asian people to come and I wouldn’t say it’s just a show for South Asians. Because all the feedback I got, men and women from any background, all related.”

“And we did have a lot more South Asian people than expected, which was nice because they came up to me and they were like: ‘thank you.'”

Mann does wonder how feedback would differ in other areas of the UK, like Bradford and its strong Asian community.

Still, this doesn’t lessen her happiness of a great response from other South Asian women. After all, she wrote Doll Face for them:

“I want them to feel like if they’ve ever been through anything like this, they’re in a space to talk about it.”

British Asians in Theatre

Doll Face is an important step for showcasing the British Asian female’s experience onstage, but what about behind it?

Karen Kaur tells us:

“I’ve always loved theatre. I’ve always said that I want a theatre career rather than Film or TV. I just love the audience and also the fact that you can get it wrong but you can always go back to it. You’ve always got another night. And it is your version of a story.”

Before adding:

“I think theatre’s a bit better for South Asian women to get their voices out there because there’s a lot more freedom. I think in Film and TV, there’s a lot more about making money.”

She perceives theatre as offering more opportunities to improve diversity. Even theatres appear to be trying harder to include British Asians, like Vinay Patel at the Bush Theatre.

Yet Karen Mann does comment on the lack of support from some:

“A lot of people say that with arts funding if you tick the right boxes…but it’s not true.”

“A lot of people are want to make it look a lot better than it is because they see it as we’re talking away their work and their standing but there’s room for everyone.”

“So no one’s taking anything away from anyone. We’re only adding and that’s how the conversation has to change.”

Building a Community

As Mann highlights there’s a huge issue in the arts with brown and black creatives facing accusations of taking up the spaces of white creatives.

While she does find this difficult, feeling that she deserves to be present as much as anyone else, Mann is using this positively.

Karen Mann has co-founded a collective for creatives, SHADES alongside British actress, Alexandra D’Sa.

With Portuguese-Indian heritage, they were both part of an all South Asian cast for Danish Sheikh’s Contempt at Arcola Theatre.

After this amazing first experience, they discussed how to change this to the norm, observing:

“We [the South Asian community] don’t collaborate very well together. We’re brought up quite competitive and it was like: ‘be the best person.'”

“You see it in our industry a bit and the only way we can change it is if we do start coming together, helping people put on work. And if we’re all in a collective, we will go see that person’s work.”

But she emphasises:

“But we don’t want it to be just actors. There needs to be writers, producers, artists, like everyone. We’re all in the same situation and it’s so lonely.”

Karen Mann underlines the importance of recognising this lack of representation behind the scenes as it’s often forgotten.

Yet to create more work for South Asians, particularly work sensitive to the reality of South Asians, she explains:

“We need more Asian writers to tell our stories. Because we can’t leave it to someone else to do it.”

“There’s so much work that needs to be done. Because I know so many people who wanted to go into the industry and they’re like our parents said no.”

“Sometimes I’m like, if I give up now, what are my cousins going to see? I’ve got young cousins and I want them to be able to see a reflection of themselves and not feel isolated and alone when you only see certain stories that are told in a certain way.”

They hope to organise an event from SHADES in the Autumn. But Doll Face represents a significant step in the right direction for British Asians.

The play offers a nuanced look at a different side of the British Asian female experience.

Deftly juggling weighty issues while entertaining through music and dance, it shows the merit of sharing South Asians stories not just for Asians, but to push the boundaries of theatre in general.

Karen Mann will continue to work on Doll Face, developing it into a longer play.

We can’t wait to see how it continues to challenge and question, as well as the other new writing Mann has in the works.

Like ‘Doll Face’, we’re hopeful for the future.