"ChatGPT knows you are there."

The language used in the House of Commons is changing, and artificial intelligence is playing a growing role.

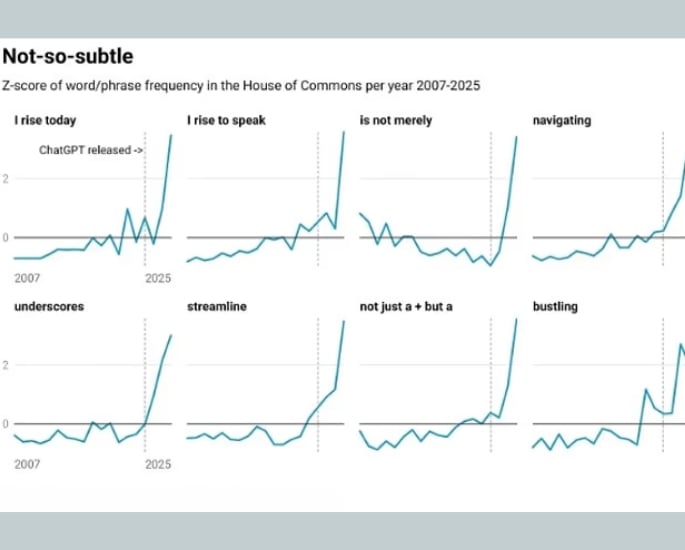

New analysis suggests that MPs are increasingly turning to ChatGPT to help write their speeches, with phrases like “I rise to speak” and “I rise today” appearing more frequently than ever.

These expressions, typical suggestions from ChatGPT, have surged since the AI tool’s public release in 2022.

Experts warn this trend could be reshaping how parliamentarians communicate, while critics argue it undermines the very traditions of debate.

The debate raises questions about authenticity, accountability, and the future of political speechwriting in Westminster.

Signs of AI in Parliamentary Language

Research conducted by Pimlico Journal highlights several patterns consistent with AI-generated text.

The study notes frequent use of terms such as “underscores”, “streamline”, “navigating” and “bustling” – words that often feature in ChatGPT output.

MPs are also employing rhetorical structures associated with the AI, including the “rule of three” and constructions like “not just X, but Y”.

While these techniques existed prior to ChatGPT, Pimlico Journal’s analysis shows their usage has risen sharply in recent years.

Hansard records reveal that the phrase “I rise to speak” has spiked dramatically, appearing 635 times in 2025 so far, compared with 231 instances across the entirety of 2024.

Tom Tugendhat, the former Conservative security minister, criticised the trend earlier this week, saying the reliance on AI reflects an “absurd” state of affairs in the Commons.

Speaking in the chamber, he said:

“All we hear from government members in ChatGPT-generated press releases is ‘I rise to speak’, ‘I rise to speak’, ‘I rise to speak’.”

“ChatGPT knows you are there. That is an Americanism that we do not use. Still, they should keep using it, because it makes it clear that this place has become absurd.”

On social media, Mr Tugendhat further questioned MPs’ independence: “If you can’t make an argument without the whips giving you the question or ChatGPT turning a handout into a speech, who are you representing? Clearly not the electorate.”

Examples Highlight Potential AI Usage

Several speeches have been flagged as potentially AI-assisted.

Wendy Morton, Conservative MP for Aldridge-Brownhills, delivered a speech on the deportation of Ukrainian children that included numerous AI-typical phrases.

Lines such as: “Few crimes are as harrowing or telling as the theft of a child… not just a relocation or an evacuation, which the Kremlin may dress it up as, but a systemic, state-sponsored assault on identity, sovereignty and humanity itself” demonstrate repeated use of the “rule of three” and the “not just, but” formula.

Similarly, Independent MP Shockat Adam’s comments on long-term medical conditions and Labour MP Mohammad Yasin’s speech on university funding also contained patterns associated with AI.

In Adam’s speech, he said: “It does not just take away people’s central vision; it also affects their ability to read, recognise faces and drive… tears are a natural result of such a devastating awareness.”

Meanwhile, Yasin said: “It is not merely a loss for humanities; it is a loss for the future of education in our nation and a blow to our global reputation as leaders in education.”

While none of these instances provide definitive proof of AI authorship, the patterns are notable, and they suggest a growing influence of generative tools on parliamentary rhetoric.

MPs Defend AI for Routine Tasks

Some MPs are open about using AI for administrative purposes.

Labour MP Mike Reader, for example, says ChatGPT helps him manage constituent correspondence efficiently.

Writing in Politics Home, he explained that AI allows him to “maximise the time available to focus on the complex work of delivering real change for the better of our country.”

Readers’ use has sparked debate about what is acceptable.

Many observers distinguish between utilising AI for routine letters and employing it to draft speeches delivered in Parliament.

The latter raises concerns about authenticity and accountability, particularly when MPs’ words are meant to reflect personal conviction and expertise.

Broader Implications for Political Discourse

The influence of AI is not limited to Parliament.

Researchers at Florida State University have identified increased usage of AI-associated phrases like “surpass”, “boast” and “meticulous” in podcasts and other spoken forums.

This indicates a wider trend in which the language of artificial intelligence is permeating everyday communication.

Critics argue that the reliance on AI could erode the art of political speechmaking.

The structured, formulaic patterns encouraged by tools like ChatGPT risk making parliamentary debate more predictable and less personal.

Yet supporters note that AI can free MPs to focus on policy, engagement with constituents, and complex decision-making.

The rise of AI in Parliament is both undeniable and complex.

While tools like ChatGPT offer practical support for managing correspondence, their potential influence on speeches and rhetoric raises important questions about authenticity and democratic representation.

As the language of the Commons continues to evolve, the challenge will be balancing efficiency with the traditions and responsibilities that underpin effective political debate.

MPs, researchers and voters alike must consider whether AI should be a helper in the background or a driver of the words spoken at the heart of British democracy.