"She emphatically reminds us that she doesn’t “speak/for ‘brown girls”."

Amani Saeed’s Split may be in two halves, but it’s irresistible to not greedily read it all in one session.

Saeed’s debut poetry collection first explores the experience of the eternal other. This is in relation to her background as Muslim living in both American and the UK with Indian roots.

However, this experience as an other is firmly linked to not only being a foreigner, but a female foreigner.

Indeed, this leads nicely on to the second half, which centres on the trauma after abuse. It’s this half that compels us to read as Saeed takes us on a personal journey with relatable touches.

Amani Saeed tackles tough subjects with no holds barred. It’s difficult to ascertain what elements come from a persona and then from her. Therefore, her poetry appears intensely personal at times, but all the more impactful for it.

Featuring illustrations from the artist, Baby Besso, DESIblitz takes a closer look at the key themes and poems in Amani Saeed’s Split.

Being a Brown Girl

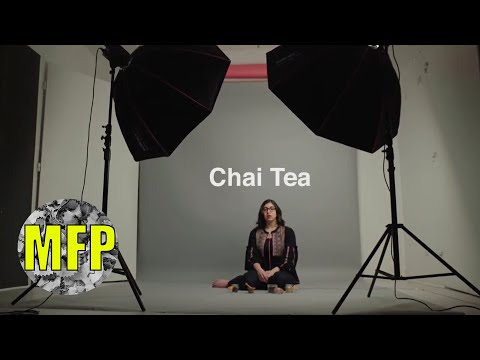

‘Chai Tea’ is the second poem in the collection and immediately captures the frustration of many South Asians with the lines:

“I was told to write my own truths;/ somehow, being brown is always one of them.”

Indeed Amani Saeed critiques the determination of non-Asians to stereotype the vast and diverse South Asian diaspora.

The poem is a masterclass in contrasts as it celebrates the varying multifaceted identities of Asians, while recognising how this group end up relating to one another because of others pigeonholing them.

She emphatically reminds us that she doesn’t “speak/for ‘brown girls”. Instead, she highlights the beauty in South Asian “individuality” like the automatic individuality of white people.

The poet celebrates the beauty of different shades of chai, coffee, and teak” among Asians, with the flourish of the rhyme and repetition of “speak”.

In fact, the poet’s talent for constructing lines adds a pace to the poem.

Amani Saeed tells us she’s “not an ABCD or BBCD”, rejecting the narrow confines of labels. The rhythm speeds up as she identifies as “a/British-born, American-raised, confused-as-hell desi”, blurring over lines and stanzas.

This continuation of sentences or enjambment comes to a sudden stop and rhyme of “tree – fuck me”.

This gives the sense that she could carry on and reiterates the inability of many to distill all aspect of their self into a neat acronym. It’s only frustration that makes this stream-of-consciousness flow grind to a halt.

Celebration and Critique

Nevertheless, the most powerful image of the poem comes from the complexity of navigating life with a non-white skin tone.

Amani Saeed conjures the story that God, the “omnipotent deity didn’t listen to auntieji”. Instead, he stained her skin when making his “morning cup of chai”.

Her imagination is hilarious in its familiarity for South Asians – even God doesn’t listen to “auntieji”. Yet, the reality of “stained skin” balances this humour because it provokes the “inevitable question:/Where do you really come from?”

Over several lovely stanzas, Amani Saeed interrogates how reductive this question and a single idea of “home” is for many Asians in the diaspora.

She shouts out “Salman Rushdie for teaching me/that my homeland is imaginary” to tracing her family history from India to Kenya to Hounslow to America. Her lines flow over as if they too are on a continuous journey.

There’s such a wonderful humour and celebratory feeling to this poem, which confronts a negative and restrictive question.

Saeed playfully describes herself as spanning “hot desert winds and Hyderabadi biryani” before moving onto “shalwar kameez that love my curved hips and/Abercrombie jeans that just won’t sit over them”.

She’s “masala dosas, samosas, mimosas”, but she brings a heartening end to the poem with a promise.

In two short and simple lines, she vows to answer “the inevitable question” with “I’ll just tell them/I come from home”.

Here, Amani Saeed takes the power from the questioner. Moreover, ‘Chai Tea’ shows the significance of language, but labels aren’t the only words with such weight.

The Importance of Names

Like labels, two poems ‘The White Question’ and Eponymous’ highlight the effect of names.

‘The White Question’ focuses on name-calling while subverting expectations as Amani Saeed directly addresses a white reader.

We read a stream of insults and jokes from “mayonnaise/cracker/redneck/pasty” to the gleeful “what’s the best flat surface to iron on?/A white girl’s ass!”

Regardless of ethnic background, the immediacy of this poem wrong-foots us. Nevertheless, after a pregnant pause, the last few lines explains these insults:

“Tell me what it does to you”.

We realise that Saeed is putting a twist on the usual experience of ethnic minorities and racial abuse. But it’s the surprise of witnessing this same treatment of the typical ‘oppressor’ that grabs our attention.

This sense of confusion is almost amusing and highlights Saeed’s strength as a poet. She has a refined ability to mitigate a lack of reservation with a highly intelligent humour.

It’s debatable that the type of reader who needs to read this poem will discover this book. Regardless, ‘The White Question’ makes a memorable statement.

Similarly, ‘Eponymous’ directly addresses this same type of reader. Amani Saeed explains the origins of her “traveller’s name” and the “richness” of its history.

This is another empowering poem and her boldness gives strength to members of the South Asian diaspora with similar frustrations.

The poet is adamant that “I have not come all this way for you/to mispronounce my name” and leaves no room for excuses that her name is difficult to pronounce. Instead, it’s the fault of the “uncouth. Uncultured. Cheap” reader.

She ends on another memorable final instruction, telling the reader “Amani./Say it.” This self-confidence is infectious, but that doesn’t mean Amani Saeed pretends to have all the answers.

Violence and War

Split has many examples of poems where the importance of language is a recurrent theme.

Saeed discusses many current debates like the controversial depiction of Muslims by the satirical magazine, Charlie Hebdo. In ‘Dear Jo’, she addresses privilege and the ‘language of hate’ against Islam, despite its links to Western Christianity.

Nonetheless, Amani Saeed considers the physical consequences for non-Westerners or ‘foreigners’ in ‘Weeding’.

There’s the graphic imagery of the persona’s nightmares of how her family’s Muslim identity makes them targets. Even if her father is a “self-proclaimed atheist”, his beard is enough to make him a target.

Amani Saeed is careful to show the point of this graphic imagery is to remind us of the humanity of victims. There’s a terrible poignancy to the corpse of her brother having “wrists/that once held a tennis racket twisted beyond fixing”.

Even more cleverly, she uses the imagery of nature of plants and weeds to show the corruption of human nature into radicalism. The poet considers how violence begets more violence as it provokes “fires to flower” and the scattering of “seeds”.

This previous use of sibilance and fricative language intensifies with the bombastic “buds bursting” and “Nazis who want to skin our sisters and slice”.

Here, Saeed’s work as a spoken word poet becomes increasingly evident.

You can almost hear the words get louder as they grow on the page with “they’re war criminals, they’re murderers, they’re -“, before she suddenly changes the tone to the quiet “is this how we get radicalised?”

There’s so much energy and urgency in Saeed’s work that it bolsters an already impactful message. The poet has previously shown her aptitude for a clever last line but here it’s much softer and sad as she finishes:

“As I look at my garden I wonder what I’ve become/and where all these weeds have sprung from.”

Amani Saeed’s ability to marry poetic talent with didacticism continues in poems like ‘Matyrdom’. She shares her frustrations with the stereotypical linking of “a terrorist/a monster/a Muslim”.

This could have quickly become repetitive for readers. Instead, her strength lies in her capacity to take a new angle on the image of Islam in the West.

Not only do her individual poems celebrate the individuality of South Asians, but Split’s first section encompasses many contrasting and sometimes conflicting views on identity – whether it’s as a Muslim, a woman, or both.

Bridging the Gap

This debut book approaches the complexity of being a woman as well as part of the South Asian diaspora.

It’s difficult to not repeatedly describe Amani Saeed’s poetry as brave for her willingness to interrogate how these identities intersect.

When there are so few definitive answers, but so many opinions, bringing together topics like women and Islam is tricky territory. ‘Brave’, therefore, feels like an understatement.

Still, Saeed’s ‘Burkini Queens’ shows how her fearlessness pays off in dividends. She touches upon everything from being too Western for the East and not speaking her ‘mother tongue’ to orientalist views of the East as “a land of dates, sand/and palm trees”.

Such poems also help her present a cohesive collection in spite of the ‘split’. ‘Burkini Queens’ and the second section’s ‘Fish’ address more universal frustrations of South Asian culture.

On the other hand, the second section addresses more personal trauma. While the poet’s experiences are sadly familiar to many women, it takes a more intimate journey through the abuse and the aftermath.

Starting the Journey: Sex and Power

Part Two of Split opens with ‘Hymen Thieves’ with the subtitle referencing the American poets, Sharon Olds.

This reinforces the universal element to the second half, which continues in ‘For Alex’ merging with a personal narrative.

‘For Alex’ introduces the persona, “just seventeen” experiencing a controlling relationship.

Inexperience means that she takes “the merest suggestion of affection” as love and feels “safer in your violence”. In fact, she’s too scared to say no when presumably ‘Alex’ of the poem possessively asks “Are you mine?”

While she takes back control by “taking off your kisses/and letting them slip down the sink”, she’s still left as a “skeleton” as ‘Alex has vampire-like sucked out the “sweetness” of her “butterfly body.

The abuse in some of these opening poems can sadly feel familiar to some.

As shown by the #MeToo movement, many women hide their experiences.

However, Amani Saeed doesn’t provide a convenient solution and a longing for the loss of innocence occurs across poems.

‘Triple Point’ and ‘Night Terrors’ are examples of this, in comparison to ‘Quantum Entanglement’ suggesting a complete “void”.

Regardless, there’s a sense of emptiness permeating all the poems and Saeed deftly highlights how violence and sex can act as a painkiller.

Unlike the constructive emotions in the first section, this half demonstrates more destructive tendencies. For instance ‘Night Terrors’ uses violence with the images of “throwing my want in their faces […] like a fist”. Then it continues “who would have thought/that being forced would have […] made me so/hungry?

But while taking us on a journey through to healing, she again approaches sex, power and violence from several angles in addition to touching on love and affection. From the scientific in ‘Quantum Entanglement’ to ‘Mama’.

In the latter, the persona implores “why didn’t you warn me, Mama?” “that sex is a power struggle”.

This approach from all angles of a subject mirrors the first half and is a compelling read. However, it’s again crucial to read the poems individually and as a collection, while Saeed contradicts expectations another time.

The Power to Love Differently

The aforementioned poems see the personas trying to find power from others, whether it’s knowledge in ‘Mama’ or violent control during sex.

On the other hand, Amani Saeed then switches tack to show the healing after abuse. Importantly, she implies there’s not a fast fix available.

Rather, the personal is crucial here in helping others consider how reclaiming their power can be a step.

‘A Rationale For Living’ finds the joy in the everyday. Saeed evokes our own senses and memories as she includes “a bowl of cereal at 11 pm” and “blanket scarves so wide/they wrap around me twice”.

She finishes “this chest shouts for life, it beats/it breathes” in a return to Split’s first half’s vitality.

We can almost visualise the ‘split’ of the collection narrow as Saeed explores the power of loving life.

We close the collection with ‘For Victor’. Worlds away from ‘For Alex’, it needs to be read after the journey through Split as well as to enjoy the poet’s gift for imagery.

Most importantly, we see how the persona finds the strength to recognise that she still has “the capacity to love […] trust […] to be unashamed.

Like Saeed’s other poems, it ends on two devastatingly beautiful last lines, which make reading Split in one sitting worthy of the time.

Final Thoughts

Split is meant to be about “coming to terms with a patchwork self that is forever being split and stitched back together”.

Of course, it’s difficult to extricate this from Saeed.

On the other hand, the book’s inscription reads “For us. And for me.” Split is so well-written that it’s possible for the debut collection to fulfil both.

The poetry is an evocative read with the poet’s gift for vivid and original images. She offers hope and confidence from her own opinions and experience without claiming absolute authority.

Above all, we go on an emotional journey with her from the determination to reject stereotyping to opening ourselves up.

This is mature debut collection from Amani Saeed and Split is likely to be just the start to a promising poetry career.