"I have to make an excuse to go out"

British Asian communities have often grappled with unspoken taboos, shaping the lives of individuals within these close-knit societies.

Diving into these stigmas, it’s important to weave together narratives from the past and present.

Whilst certain constraints are normally associated within South Asian countries specifically, do British Asians still suffer from taboos of the past?

Or, are there new problems that these communities face?

Likewise, what impact are British Asians having on the lifestyle of future generations? Are they changing the scope or still stuck in navigating their own journey?

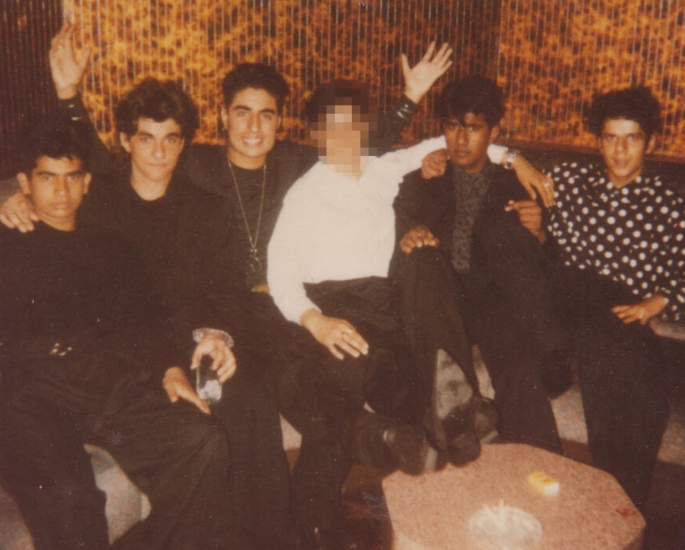

The Daytimers Phenomenon: A Glimpse into the Past

Within British Asian history, the 80s – 90s witnessed a unique cultural phenomenon known as ‘daytimers’.

Born out of necessity, these events allowed young British Asians to experience the thrill of nightlife without the watchful eyes of strict parents.

These gigs were popular in the West Midlands and parts of London and attracted fans of the Bhangra bands who played live at well-known venues like The Dome in Birmingham and Hammersmith Palais in London.

Attendees, especially, young girls would change into daring outfits in public toilets before immersing themselves in these lively daytime gigs.

Daytimers were a clandestine rebellion against cultural norms.

Strict South Asian parents forbade nighttime outings, pushing a whole generation of young British Asians to create a secret world of self-expression during daylight hours.

The anticipation of transforming from school uniforms to stylish attire, the thumping beats of Bangara, and the unbridled freedom to dance and socialise made daytimers a pivotal part of British Asian history.

While daytimers may have faded into the recesses of history, their impact lingers.

The strategic excuses employed to attend these gigs emphasised the need for secrecy in a society that frowned upon such revelry.

Despite the challenges, these events were crucial for the burgeoning DJ scene.

Artists like Bally Sagoo and Punjabi MC began to develop the remix era in music popular at the time, such as Bhangra and Bollywood tracks.

However, this liberation came at a cost, as societal pressures and consequences awaited those caught in the act.

Furthermore, the taboo associated with British Asians going to nightclubs stems from especially parental fears of their children becoming ‘like the British’, getting attracted to immoral behaviours, and drinking or taking drugs.

Because music had its connection with the so-called ‘loose society’, and those following it were going against cultural norms and expectations, especially girls.

Many British Asians still find it difficult to explain to their parents that they’re going out with friends or want to attend a party at night.

A lot of parents associated clubs and parties with foolish behaviour, drunken antics and naughty behaviour.

There is a lot of judgment towards those who choose to go to nightclubs, even if their parents seemingly agree to it.

Naima Khan from Birmingham explains:

“If it’s past 7 pm, I have to make an excuse to go out, even if it’s something innocent.

“My parents think I should be inside at nighttime but this is England, we need more freedom.”

“I know a lot of my friends still have to say they’re going to the library to try and meet up with friends in the evening. It’s ridiculous.”

So, whilst daytimers provided a gateway for young British Asians to experience the thrill of clubs, it seems it portrayed a taboo that is apparent in modern times.

Divorce in British Asian Communities

Divorce has long been a sensitive and taboo topic within British Asian communities.

Rooted in strong cultural values that prioritise marriage and family unity, British Asians often grapple with the stigma surrounding divorce.

The Fourth National Survey of Ethnic Minorities in the 90s revealed a divorce rate of 4% among British Asians, significantly lower than other ethnicities.

Marriage is revered as a sacred bond, and divorce carries a heavy stigma, impacting not just individuals but entire families.

Cultural expectations emphasise family honour, social reputation, and community standing, creating immense pressure to stay in marriages, even in challenging circumstances.

Recent years have witnessed a shift in attitudes towards divorce within the British Asian community.

Factors such as increased education, empowerment of women, and changing societal norms contribute to a growing divorce rate.

The Office for National Statistics reports a 39% increase in divorce rates among British Asians between 2005 and 2015, reflecting changing dynamics and evolving perspectives on marriage.

However, whilst the divorce rate is higher, the question remains about whether this is accepted by British Asian families.

34-year-old Manprett from Nottingham explains the aftermath of her divorce:

“I don’t believe divorce is accepted at all.

“When it was finalised between me and my husband, I got so many questions asking me to stay with him and stick it out.

“When everyone found out, I got so many looks and stares from my own family at events.”

“Once a major thing happens, every auntie and uncle know about it and they’ll explain it in a way that dismisses the true reasons behind the divorce.

“Then, those living in the past will think you’re tarnished and no one will marry you again.”

While progress is evident, inter-generational conflict persists as younger British Asians prioritise personal happiness over upholding cultural traditions.

The clash between traditional values and the evolving norms of the adopted country contributes to higher divorce rates.

The community grapples with the notion that divorce can be a viable option for those in unhappy and abusive marriages.

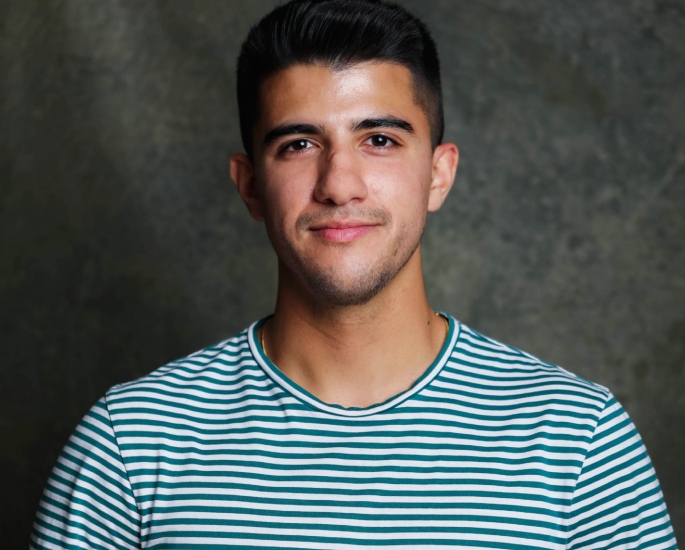

Navigating Mixed-Race Identities

The taboo around being a mixed-race British Asian stems from deeply ingrained cultural norms and historical perspectives within traditional South Asian communities.

While attitudes are evolving, certain challenges and taboos persist, contributing to the complexity of navigating a mixed-race identity within the British Asian context.

Traditional South Asian communities often place a high value on preserving cultural and ethnic identities.

There is a fear that marrying outside one’s ethnic or cultural group could dilute or erode these identities.

This leads to concerns about the loss of cultural practices, languages, and traditions.

Furthermore, those with a dual identity could be perceived as “less authentic” or not fully belonging to either cultural group, creating a sense of isolation.

This can be particularly challenging when individuals feel caught between two worlds, neither fully accepted within their South Asian heritage nor completely assimilated into Western culture.

For example, Joshiv Miller, a student with an Indian mother and Irish father reveals:

“I actually feel like I’m more Indian than I am Irish, or white.”

“I spend more time with my Asian cousins, listen to Punjabi music more and even go to bhangra lessons with them.

“It’s weird because I’m pale as anything, have blue eyes and blonde hair.

“But when I go to big parties with my mum, a lot of people will think I’m a family friend or distant cousin. They don’t see me as fully ‘theirs’.

“I know I’m neither here nor there but it’s hard because my wider Asian family don’t see me as theirs and my Irish family don’t see me as I belong to them.”

Historical norms and practices play a significant role in shaping contemporary taboos.

While traditional attitudes persist, there is a noticeable shift in younger generations toward more open-minded perspectives.

Young British Asians are often more accepting of mixed-race identities, reflecting broader societal changes and a growing recognition of diversity within the community.

Navigating the taboos within British Asian communities involves confronting historical legacies, challenging cultural norms, and celebrating the diversity that defines identity.

Embracing change and fostering understanding can pave the way for a more inclusive and compassionate community.

As the British Asian community continues to evolve, it is crucial to recognise and respect the varied experiences that contribute to the tapestry of its rich heritage.