"Our body hair was laughed at as people pointed out our upper lip hair."

British Asian students from South Asian communities in the UK are at times subjected to negative stereotypes.

Many students have experienced the feeling of being treated differently than their peers at some point during their school or university journeys.

Ultimately, this treatment is disadvantageous depending on the type of stereotype they are associated with.

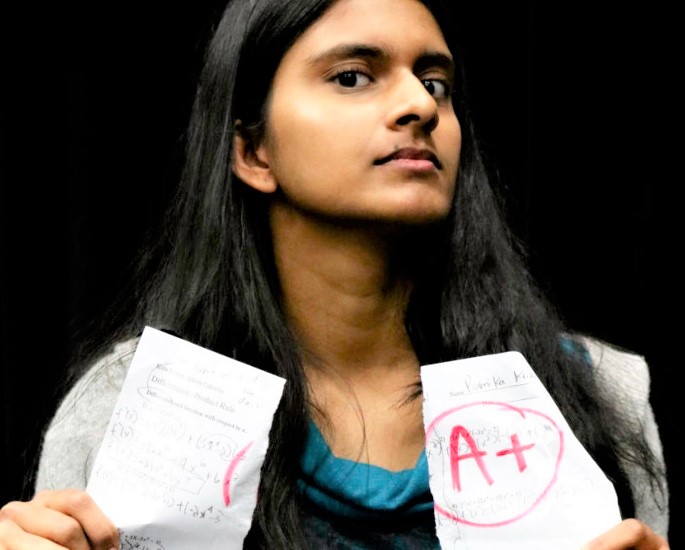

In the academic sphere, South Asians are typically associated with positive attributes. Asians, in general, are deemed to be the ‘model minority’ as they often appear to be intelligent and hard-working.

The cause of this could be that South Asian parents have high aspirations for their children; they encourage them to push themselves, work hard and be ambitious.

However, this may be more relevant to British Indians.

Typically, in the South Asian category, British Indian students outperform other students from Pakistan and Bangladesh backgrounds.

For example, at the GCSE level, British Indians average attainment was 70.4%, whereas British Pakistanis have an average of 47.8%.

Although the attainment gap is quickly closing, these statistics raise the question of why certain South Asians continue to underachieve.

The truth is, while South Asians are largely connected to positive stereotypes, there are many prejudices held against them.

Factors such as race, gender, ethnicity, and social class can all contribute to the marginalisation of any group of people, and Desi kids are no exception.

Common negative stereotypes about South Asian students may include bad English language skills, a cultural dress sense, and the typical ‘smelling like curry’.

However, these stereotypes are reinforced by teachers, pupils, and even the education system itself.

Though this may seem harmless on the surface, its effect on children is detrimental to their educational achievement and self-confidence.

DESIblitz explores the different ways South Asian students are subjected to negative stereotypes and the effects this causes.

Teachers

According to research, ethnic minority children in the UK have a more negative school experience than those from white backgrounds.

This is because the way teachers perceive and interact with their students is critical to their educational success and experience. Which has been the foundation of unfair prejudices for decades.

In an ethnographic study by Cecile Wright, she found that ‘teacher labelling’ affects British Asian students negatively:

“Although the majority of staff seemed genuinely committed to the ideals of treating students from different ethnic backgrounds equally, in practice there was discrimination within the classroom.”

Wright found that primary school teachers unknowingly had stereotypical presumptions about Asian students.

They assumed the pupils would have a poor command of the English language, so they excluded them from class discussions and used ‘dumbed down’ language when speaking with them.

Being negatively stereotyped from such a young age will inevitably have a transformative impact on the students.

Many of the students in Wright’s research had become ambivalent about school as the education system became one that they couldn’t relate to and were not welcomed into.

The findings in her research were proven in another study done by Paul Ghuman in 2001.

Although Ghuman specifically focused on British Asian girls, he found an unjust amount of stereotypes that still exist in UK schools.

Within the research, a Black British headmistress of a ‘majority Asian girl school’ stated:

“When I took over the headship, I was appalled by the attitudes of senior white (mostly men) teachers.

“They had given up on Asian girls’ education – A typical comment was: ‘They are going to be married off as soon as they leave school, so what is the point of raising their expectations?’”

It is important to recognise here that most UK teachers are white. Unknowingly, they can make false assumptions about their students due to a lack of communication and exposure to different cultures.

Language Barrier

Unfortunately, this stereotype is also very prevalent in higher education such as secondary school and university. Where accent prejudice is an upcoming problem.

A 2020 investigation by The Guardian revealed that:

“Students past and present reported bullying and harassment over their accents and working-class backgrounds.

“Some said their academic ability was questioned because of the way they spoke.

“The Social Mobility Commission (SMC), which monitors progress in improving social mobility in the UK, described the situation as unacceptable and said accents had become a ‘tangible barrier’ for some students.”

According to the same report, some students getting ridiculed prompted them to leave education behind.

There have also been accounts of students getting judged and penalised for speaking non-traditional English.

Students are, therefore, trained to suppress their accents and forced to conform to an unnatural ‘British’ voice.

This only serves to reinforce the notion that Desis are not acceptable in their own right.

However, in cases when South Asian pupils are genuinely unable to keep up with the English language, some teachers make little effort to adapt to the student’s English language skills.

Some teachers fail to adjust their language so that South Asians from poorer backgrounds can keep up. Students in this position can feel intimidated or discouraged.

This is because South Asians, who are typically from working-class families, are not raised speaking an elaborate language that is often used in middle and upper-class households.

This can limit their English fluency, to where British Asians begin to modify the way they talk and converse.

In a 2010 article by Maya Zara, she reported how British Asians inherit the twangs and non-native sounds of their migrant parents, which is deemed as a ‘foreign accent’.

She further stated:

“The parents stressed the importance of the language for economic attainment, and the children have seen at first hand the hardship that a lack of proficiency may cause.

“The children were receptive of these foreign features in their parents’ speech, and although they use these when chatting among friends, the sounds are used much less in formal contexts.”

This shows that students are instilled with the idea that a well-spoken person is deemed more employable and professional.

Which enables British Asians to suppress the distinct elements of their accent – something which should be celebrated rather than ridiculed.

Beyond this, students also fall into the trap of the self-fulfilling prophecy, where the process of labelling children can contribute to the identities which students form.

For example, Desi children may find themselves genuinely developing poor language skills as a result of being told that this is their identity and nothing more.

If a child is raised with both unconscious and obvious racial stereotypes, they may eventually believe those prejudices to represent who they are.

Unsupportive Peers

When teachers act in such a way, students begin to catch on.

They see their teachers normalising the art of stereotyping, and they begin to do the same. This is, even more, the case in primary schools when kids are still at an impressionable age.

However, once students realise what racial profiling and discrimination are, their minds are extremely conflicted between identities.

Not only do Desi pupils form friendships and want to fit in with British ideologies, but they also want to embrace their own culture and do it freely.

However, if groups are not openly discussing the backgrounds of their Desi friends, then it introduces a hierarchy, perhaps unconsciously, where British culture sits above the rest.

In a McPin Foundation blog post, Humma Andleeb discusses the collision of the British and South Asian cultures:

“I am a second-generation Pakistani and I attended a school with a predominantly white-British demographic.

“I felt like I was living two lives; on one side I was trying not to disregard my background and upbringing, but I was simultaneously trying to fit into the society in which I lived.”

Humma emotionally adds:

“The need to conceal aspects of your life in multiple contexts leads to grief.”

The lack of intervention from other students emphasises this loneliness more. A feeling that academic establishments continue to neglect.

Michaela Tranfield, an English undergraduate at Kings College London, dived into her understanding of racism in the British education system through her experiences:

“Racial abuse and throwaway comments have been condoned by British society and either ignored by teachers or worse still, orchestrated by them.

“It breeds a culture of racist attitudes and biases weaponised against young Black, Asian and Latinx people for the comedic satisfaction of others, making them question themselves and feel ashamed of their identity.”

For example, Desi names are often laughed at and ridiculed for being complicated or, in other words, not tuned to the white ear.

Tranfield continues:

“I was told that I didn’t smell like an Indian or wasn’t like other Indians, as if it something I should be thankful for.

“Our body hair was laughed at as people pointed out our upper lip hair.

“Some found it incomprehensible that we could grow hair on our hands and arms, one even calling me a monkey because of how hairy they thought I was.”

As students’ home lives and school lives are so dissimilar, these judgments ultimately lead to a clash of South Asian identities.

Therefore school environments become alien to South Asian children as a result of being on the receiving end of discrimination.

Even in a classroom, learning becomes difficult when people constantly make you feel inferior.

There have been reports of South Asian students being intimidated, ostracised, and occasionally beaten in predominantly white schools.

Wright’s research suggested that a way in which students were ostracised was by refusing to play with them.

She concluded that this made:

“Minority ethnic values and culture appear exotic, novel, unimportant, esoteric or difficult.”

Although this humiliation has died down, the issue continues beyond the playground.

In correlation to the rise of social media, cyberbullying has also increased.

Constantly being subjected to racist comments, within and outside of school grounds, South Asian children may feel shame and embarrassment.

This is one of the reasons that cliques form. Students believe that because their culture has been rejected so many times, no other race will accept it.

The Education System

From the curriculum to institutional racism, the education system itself provides a platform for South Asian students to be negatively stereotyped.

Starting with the curriculum, there is almost no South Asian representation in school textbooks and classes.

Arguably the only time students learn about South Asia is when discussing Gandhi in religious education.

This is because the UK’s curriculum is whitewashed.

British schools give priority to white culture in most areas of the curriculum. For example, history lessons are deeply rooted in British monarchs and successes.

For this reason, South Asian students may underachieve as they feel like the curriculum is not relevant to them.

In 2017, the BBC programme Newsnight marked 70 years since the 1947 partition of India.

Within the show, there were many audience members, including the priest, Canon Michael Roden, who called for the addition of Indian history into the UK curriculum. Roden stated:

“I was in secondary school in the 70s and I learnt about Clive of India, the Indian mutiny and then learnt about Gandhi by watching the film, that was the sum total of my historical knowledge.

“I thought ‘I am sure that my children who are at school will be learning all about India, Pakistan and Bangladesh and the history’, then I realised they are learning less.”

Unfortunately, this lack of coverage has tainted the historical importance of these South Asian countries in relation to the UK.

Not only is it important for British Asians to understand their history, but it is equally crucial for other pupils to learn about it too.

The literary lead of South Asian Heritage Month (SAHM), Natasha Junejo, shared this same frustration:

“It is difficult to come to terms with a history of subjugating people, raping and pillaging of lands and the slave trade – it doesn’t align with the historical memory of being ‘the saviour’.

“Because we don’t talk about the fractious, difficult and uncomfortable side of colonial history, they do not understand why there are so many people of colour here, who arrived as citizens.”

Critically, learning about the good and bad of different cultures is imperative for unity and progress.

In addition, institutional racism has similar effects of isolating Desi children.

This is the way in which education, as an institution, unintentionally discriminates against minorities. For example, not permitting holidays for Eid but allowing three weeks off for Christmas holidays

Also, some students are asked to remove religious items such as their hijab or bracelets for safety precautions.

These examples are especially harmful to Pakistanis and Bengalis as most of these pupils practice Islam.

By requesting such things, the system desensitises pupils to their beliefs, making them believe that religious and cultural practices can be turned on and off like a switch.

Through this process, students reach one step closer to conforming to traditionally British customs.

Underrepresented

In addition, the lack of South Asian role models in schools contributes to the ignorance of both teachers and other students.

The truth is that white students may stereotype Desi students because they do not interact with their culture.

GOV.UK published some interesting data in February 2021, which highlighted that in 2019, 85.7% of all teachers in state-funded schools were white.

The alarming figure reinforces the misrepresentation within UK schools and the troubling thoughts this can cause for British Asian students.

Pupils going around their hallways and classrooms without seeing their background represented can feel vulnerable, lonely, or excluded.

In addition, seeing a predominantly white teaching staff can indicate that the profession is unnatural for British Asians to obtain.

In this case, silence speaks louder than words and their invisibility in the curriculum definitely does not go unnoticed.

Ultimately, the UK’s education system fails to provide South Asian students with adequate support, both in and out of the classroom.

As a result, many Desi children end up self-perpetuating these issues, knocking down their confidence and interest in education in the process.

If not this, some students become conformists, where they simply accept that South Asian culture has no place in Britain.

Either way, both are very clearly damaging for students of any minority.

Changing the Curriculum

Although it seems like we are too far gone, there is still hope for the future as increasing diversity has many activists fighting for the abolition of negative South Asian stereotypes.

With more Desi role models and children being exposed to different cultures through the internet, the chances of experiencing such negative stereotypes may come to an end.

In June 2020, a petition to make Black and Asian history part of the national curriculum to battle racism was signed by thousands across the UK. However, it was rejected by the UK government.

Although, in 2021, The Guardian reported that “more than 660 schools in England have signed up to a diverse and anti-racist curriculum.”

This sends out a clear message to British South Asians that a long-awaited breakthrough is finally coming.

Until that day comes, advocating to remove prejudice towards all kinds of groups should be central to the UK’s development as a nation.