"Until I'm married something like that can't happen."

The landscape of Britain Asian communities has changed a lot over the past five decades. As a result, new doors have opened up for British Asian women.

However, the fact remains that British Asian women continue to face many challenges.

Some of the challenges that Desi women face are similar to the challenges their mothers and grandmothers encountered.

Whilst other challenges are much newer, there are still outdated ideologies that have not evolved or changed.

Either way, the challenges are a consequence of multiple factors such as changes in societies structure and the advancement of digital technology.

In addition, the confusion of dual identities plays a part in the challenges British Asian women face. As well as the “triple burden” many women face in 2021 – emotional/physical labour at home, childcare and work.

Here, DESIblitz takes a look at 15 challenges British Asian women face and the severity of these obstacles.

Misconceptions of Desi Food

British Asian women are challenging and challenged by misconceptions of South Asian cuisine.

Desi food within the home evolves and changes but its diversity can be underestimated.

Curry is a popular term for South Asian food in Britain. Although the word does not reflect the wide variety of dishes that exist.

Consequently, there has been much debate over the appropriateness of using the word ‘curry’ and so we are seeing more Desi women and men challenge perceptions of their own cuisine.

As a well-known phrase for South Asian food in Britain, curry does not reflect the rich variety of dishes that exist.

Aliyah Khan*, a 32-year-old Pakistani graduate student from Birmingham, maintains:

“We have only two Pakistani dishes in our family that we refer to as curries, nothing else.

“But I’ve heard plenty of British non-Asians use curry as a term to refer to all South Asian food.

“Younger me kept quiet, now I make sure to highlight the real names of dishes.”

Aliyah goes onto say:

“It’s a challenge we need to face, it seems a bit stupid on the surface, but it matters.”

Furthermore, Californian food blogger Chaheti Bansal in a video, called for the word curry to be cancelled:

“There’s a saying that the food in India changes every 100km.

“Yet we’re still using the umbrella term popularised by white people who couldn’t be bothered to learn the actual names of our dishes.

“But we can still unlearn.”

Each region of Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and Sir Lanka have unique flavours and distinctions in their dishes. It’s what makes South Asian cuisine so rich and vibrant.

Within British Desi homes, Desi food still holds a significant place. It is a tie that British Desi people have, connecting them to their South Asian heritage.

Also, learning to cook and adapting Desi food is also a bonding ritual between generations.

However, if women are constantly exposed to the stereotypical word “curry” for every South Asian dish, it downplays the significance of Desi food.

As well as shunning the cultural importance that food is within South Asia and British Asian communities.

Asking Permission or Not?

Unlike when South Asian women first migrated to Britain, British Asian women have more freedom of movement in 2021.

It is more natural within modern society for British Asian women to be independent. Women go to university, travel, work in different cities and much more.

However, culturally unmarried British Asian women are still seen as the responsibility of their parents.

As a result, one key challenge unmarried Desi women can face is getting parents to see that they are adults. Adults that do not need to ask permission to do things or go somewhere.

*Hasina Begum, a 32-year-old Bangladeshi bank worker based in Birmingham states:

“It’s so hard, I reached 24 and realised I was still asking permission to do things and go places. Unlike my brothers, it was just automatic.

“Luckily, over the years, I’ve been able to change that habit, and my parents haven’t resisted.

“Now I’m still considerate. I check my parents don’t need me for anything, and then I book my holidays and go out with friends.

“I just don’t ask permission.”

Hasina then says:

“But I have friends who feel they have no choice and that marriage is the route to freedom and control.”

Moreover, Ruby Shah, a 23-year-old Pakistani graduate residing in Birmingham, feels the tension of navigating through this confinement:

“I may be an adult, but in my family, none of us unmarried girls can do things like the boys. It’s so damn frustrating.

“My dad always says that I can travel abroad alone and with friends after I get married. So until then, any holidays are with the family.”

She continues to reveal:

“Don’t get me wrong, I work, go out with friends, wear what I want.

“But certain things I can’t just do unless the parents – mainly my dad agree to, and dad never agrees.”

This illustrates how difficult it still is for some South Asian women to obtain ‘freedom’. Although most Desi parents are more accepting of how society is, they still enforce traditional ideologies which are outdated.

Unmarried & The Expectation of Living with Parents

Another challenge many British Asian women face is opposing the cultural norm of living with their parents until they are married.

With more Desi women getting married when they’re older, staying in the parental home can be taxing.

Even where Desi parents would be comfortable with their daughter moving out, cultural judgments can be a barrier.

Ruma Khan*, a 30-year-old Pakistani youth worker based in London reports:

“My parents were happy for me to move out but I knew that my extended family and elders in the community would not stay quiet.

“So that stopped me from moving out. The good news was I found a job in London and that gave me a justifiable reason to move out.”

She goes on to declare:

“Some family members still had their nose out of joint, but the voices weren’t as loud.

“If I had stayed in Brum and moved out of home, it would have been bad.”

In contrast, Reva Begum*, a 23-year-old student from Birmingham asserts:

“There is no way my dad and brothers would be ok with me moving out permanently, they’d throw a fit.”

She then declares:

“Until I’m married something like that can’t happen.”

In the 21st century, British Desi women can have experiences that decades ago would have seemed impossible or led to family conflicts. Yet they still face compelling challenges in their everyday life.

British Asian women live in a society where the emphasis is on the individual and their needs and desires.

However, they live within a culture where the focus and emphasis are on the collective. Thus they can be conflicted when it comes to doing what they wish to do and what is expected.

Juggling Family & Work Responsibilities

Unfortunately, within some British Asian communities, patriarchy still dominates. Hence, Desi women face pressure to juggle home and work responsibilities efficiently.

Cultural expectations around Desi women’s roles have expanded. For example, working outside the home and being a breadwinner.

Yet, there is still an assumption and idealisation that her work responsibilities should not impact her role in the home.

There is a belief that married or unmarried, work responsibilities should not hinder a Desi woman from taking care of her family and home.

Research done by the Department of Work and Pensions in 2007 looking at British Pakistani and Bangladeshi women found:

“The employed women interviewed…said that they had made a conscious effort to fit their work around their childcare responsibilities.”

The expectations placed on women are made worse by the global reality that housework and child-rearing are not seen in the same way as a progressive career.

Razia Khan*, a 28-year-old British Pakistani teacher, said:

“My husband is great; we both teach, so he gets that when I come home, I don’t want always to be cooking.

“But it did cause issues with my traditional in-laws. In-laws disapproved of how me and my husband split the chores and cooking.”

Razia continues to highlight:

“I was meant to be doing it all in their eyes. For them, work shouldn’t impact what I do at home.”

“When I would ask, ‘what about *Ishanne?’ (her husband), they would say that’s different. So we bought our own place.”

Similarly, Saba Khan*, a 24-year-old Kashmiri graduate from Birmingham explains:

“My mum is 50 now and has worked since I was five and she does everything. Before she goes to work, she gets my dad up and always fixes his breakfast.

“After work, if I can’t cook, she does. My dad only eats Asian food and won’t cook.”

Unfortunately, the intensity of trying to juggle a career and maintain a home is still a prevalent challenge amongst British Asian women. A tradition that needs to be broken.

In hindsight, many Desi marriages are becoming equal but not at the pace that is required.

Therefore there needs to be more awareness raised within British Asian communities to help rectify the equality of women.

Pressure to Conform & Meet Beauty Ideals

As much as British Asian women face societal and cultural challenges, they also face personal hurdles in deciding to conform to or reject beauty trends. This is true of Desi women globally, not just within the UK.

Although beauty ideas change, the one prominent view positions ‘fairness’ as the dominating aspect of beauty.

Such outlooks are reinforced by Desi women prominent in music, cinema and popular culture, most of whom fit the eurocentric western idea of beauty.

Thus, British Asian women still face these compelling hurdles, especially with the significance of social media which bolsters standards of beauty that aren’t inclusive of South Asian women.

This can lead to many Desi people feeling they need to:

- Lighten/bleach their skin.

- Lose weight.

- Remove facial and body hair.

Alisha Begum*, a 27-year-old British Bangladeshi passionately declares:

“It’s rubbish, but the fact is Asian girls who are light and thin do better than the girls that are opposite to them.

“Since I was a kid, through family, the community and media, I’ve learnt that. I’ve started pushing back but it’s so hard.”

Researchers Fahs and Delgardo asserted in their 2011 research that the racially coded nature of beauty narratives and ideals cannot be forgotten.

They maintain that British Asian women can feel pressurised to enact European paradigms of beauty. This then leads to a “lifelong commitment to continue to try and control/regulate their resisting bodies”.

Such narratives and ideals mean Desi women continue to face challenges when it comes to decisions over their appearance/body which can lead to more severe issues.

Saying “I Don’t Want Children”

Worldwide, Desi women are raised to see marriage and motherhood as an inevitable end goal.

Thus, British Asian women who do not want children face the challenge of going against expectations and facing assumptions of infertility.

Feminist writer Urvashi Butalia examined the dilemma of an Indian woman opting out of motherhood:

“How often have we heard that a couple is childless, that a woman who cannot bear a child is defined as barren.

“Why should this be? I did not make a choice not to have children, but that’s how my life panned out.

“I don’t feel a sense of loss at this, my life has been fulfilling in so many other ways. Why should I have to define it in terms of a lack?

“Am I a barren woman? I can’t square this with what I know of myself.”

Furthermore, Eva Kapoor*, a 35-year-old Birmingham-based Indian beautician, asserts:

“I like kids, but I’ve never wanted to have the responsibility to raise them.

“I also have no desire to give birth. I’m an aunt to my siblings and friends kids, and that’s fulfilling enough.”

She goes on to highlight:

“But so many people don’t get it. I’ve had questions about my fertility, people saying adoption is an option.

“When I say I don’t want kids, some say I’ll change my mind.”

The frustration Eva feels when she receives such remarks rippled through her voice.

Also, Miriam Shabir*, a 44-year-old British Pakistani office worker, states:

“Neither my husband or I ever wanted kids, something most of our family do not understand.

“Many of our older relatives have said ‘then what’s the point of you being married?’. They believe marriage equals kids.”

In such a modern society, it is surprising to try and solely define women as naturally maternal and wanting kids. Accordingly, British Asian women who contradict this face significant backlash from their community.

As previously mentioned, British Asian women are more independent now. Therefore, choosing to not have kids is part of their rights and should be respected.

In such a demanding climate, burdening Desi women with a fragile topic like childbirth is regressive and needs changing. Something that needs to be started at the heart of South Asian communities.

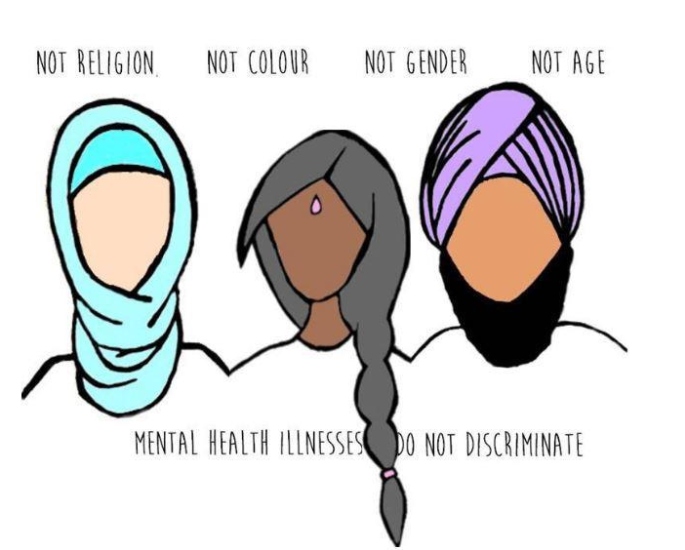

Vocalising Struggles with Mental Health

Notably, discussions of mental health and wellbeing have become more mainstream. However, within Desi communities and families, such topics remain quite taboo.

Hence for British Asian women, openly discussing and dealing with mental health concerns can be challenging. As can shifting entrenched cultural norms and expectations of ‘sucking it up’ and getting on with it.

NHS figures show that a white person is two times more likely to seek help than someone who is Desi or black.

Tammy Ali*, a 50-year-old British Pakistani woman from Leeds pointed out:

“When I was younger you just got on with it. Mental health was not understood.”

In addition, Razia Khan* goes on to state:

“Today it’s different, even so in Asian communities you are not judged positively for having a mental illness.”

“My youngest niece has severe depression and only her mum, sister and me know. Her mum asked her and us to keep it quiet.

“It could impact the rishta (marriage) she gets later. Also, her mum doesn’t want gossip to hurt my niece.”

Stigma, stereotypes and misconceptions around mental health and illness within Desi communities is still abounding.

Views of Professionals

Dr Tina Mistry is a clinical psychologist and founder of the Brown Therapist Network.

In July 2021, she was in conversation with Sky News about the stigma of mental health in South Asian communities and declared:

“‘Talking about the fact that somebody might be struggling’ comes with ‘huge stigma’ in the South Asian community, and often there’s ‘a lack of awareness of what services are out there’.”

Plus, the one size fits all framework the NHS uses to support patients means that Desi women’s and men’s needs are not met.

Marcel Vige, head of equalities and improvement at the mental health charity Mind told the BBC:

“People from South Asian communities often tell us the strong sense of community and importance placed on family can be a very positive thing for their mental health.”

“But for many people, the need to preserve the family’s reputation and status in such close-knit environments can lead them to remain silent about their own feelings.”

He then highlights:

“Previous research suggests that pushing those feelings down can lead to increased worry and can contribute to the disproportionately higher rates of self-harm within South Asian women.”

Although the mental health ‘stigma’ is attached to both Desi women and men, taking into consideration the other challenges Desi women have to face, they can feel an overwhelming sense of pressure.

Social Media Racism

Digital media technologies and the anonymity of social media has changed many things for British Asian women.

The digital realm means British Desi women face the challenge of dealing with social media racism.

The Institute of Race Relations found that 85% of all hate crimes reported were race-related in 2014.

Susan Williams, the Home Office minister for countering extremism, stated in 2020:

“I’ve been speaking to our hate crime lead, and there’s been a 21% uptick in hate incidents against the IC4 (East Asian) and IC5 (South Asian) community.”

In addition, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) found in 2020 that one in five children aged between 10-15 experienced online bullying.

This shows how the trajectory of social media has impacted the rate of online bullying cases.

More importantly, it indicates within a modern world, children, including Desi girls, are subject to bullying at a younger age. This can lead to further confusion and challenging periods within British Asian women’s lives.

Moreover, the UK government is attempting to tackle the high rates of bullying with the 2021 Online Safety Bill.

This aims to tackle harmful content online by placing a duty of care on online platforms to keep users safe.

Companies will need to comply with rules by carrying out risk assessments for specified categories of harm. Independent regulator, OFCOM, will publish a code of practice for them to follow.

If companies fail to comply, OFCOM has the power to issue fines. Fines can be up to £18 million or 10% of global turnover, whichever is higher.

However, some remain uncertain about this enforcement and its success.

For example, Zobia Ali*, a 25-year-old British Pakistani student, stresses:

“Policy is all good in principle, but in practice, there will be difficulties in enforcing. I know plenty of Asians, me included, that get racism online. Legislation hasn’t stopped it yet.”

Zobia continues to explain:

“Sure some messages are flagged and removed, and I can block users, but then another will come.”

In an environment where the government lauded the highly problematic Sewell Report, there is much work to be done.

This specific report was challenged by Runnymede, a race-equality think tank, who declared that in the Sewell report:

“The government have insulted not only every ethnic minority in this country.

“The very people who continue to experience racism on a daily basis.

“But also the vast majority of the UK population that recognise racism is a problem and expect their government to contribute to eradicating it.”

British Desi women continue to face the challenge of dealing with social media racism. A multi-dimensional attempt to address the entrenchment of racism in Britain with governmental support is needed to change this.

The Silence on Sex & Sexuality

Today many British Desi girls date and have active sexual lives. Yet to what extent can they discuss issues of sex and sexuality at home?

Times have evolved but cultural ideologies still restrain the conversations British Asian women can have.

Norms and expectations mean Desi women face the challenge of expressing themselves without causing family/community shame and horror.

Although there is an indication that children who discuss sex with their parents are more likely to engage in safer sex and are less likely to contract a sexually transmitted disease (STD).

However, the traditional nature of Desi culture prohibits such open conversations.

Consequently, many Asian parents are unwilling or unable to have open conversations about sex and sexuality, especially with their daughters.

Meena Kumari*, a 34-year-old stay at home mum, remembers:

“My mum waited just before my wedding to have the sex talk and it was so vague and told me nothing.”

She continues:

“She didn’t mention contraception, orgasms, nothing. I may have wanted to hide in a hole if she did, but I did want something more than what I got.”

In Desi households, sex education can be a difficult conversation, but talking about female sexuality can be even more taboo.

Elishbha Kaur*, a 23-year-old British Indian student in Birmingham, recalls:

“I remember trying to tell my mum I was bisexual, more than once.

“We had discussions about me getting married at some point and I finally smoothly said, ‘yes, I want to get married, but don’t know if it will be a man or woman’. Her reaction was – nothing.”

“Mum ignored it. She changed the subject; this happened more than once. I tried, all I can do.”

Elishbha, like many British Asian women, is forced to try and explore her sexuality in the shadows of her family and community.

Not only does this make it more challenging for women to seek the right advice but forces them to suppress themselves around their own family.

“Too Educated” Equating to being Difficult

In Britain today, British South Asian women have more choices regarding their education than previous generations. This is the case for many across the South Asian diaspora.

Government data reveals that in 2020 females outperform males in the main attainment measures across the UK, making up a bigger share of higher education students (57%).

They also have a higher level of qualification among 19-64 year-olds (46% with NQF level 4 or above compared to 42% for males).

However, this brings its own challenges within British Asian communities for women. An idea that exists is that there are negative consequences to women being “too educated”.

For example, Bismah Amin*, a 30-year-old single mother residing in Birmingham, asserts:

“When my parents were looking for a rishta, and sending my CV out to potential grooms, my education was at times an issue.

“The matchmaker would come back saying the guy or his family felt my graduate degree was too much.

“They wanted someone with a Bachelors since that was what their son had.”

Bismah humorously recalled that for her, her educational background was a shield keeping unwanted suitors away:

“I was told my mum cried a few times and worried a lot. My brothers stressed since they couldn’t get married until after me.”

Nevertheless, this is not how everyone in the Desi community feels.

Imran Shah*, a 30-year-old Indian Gujarati worker in Birmingham, stresses:

“There is no such thing as a woman or anyone being too educated, in my eyes.”

Imran goes on to report:

“But I have friends who think so, or their family does.

“They think more education means more chance of backtalk and the woman standing her ground in the family. Very old school.”

This idea of women being “too educated” correlates to ‘danger’ or something negative is tied to patriarchy and fears of female power and empowerment.

Talking About & Taking Action Against Abuse

Furthermore, another challenge that British Asian women face is talking about and taking action against domestic, sexual, and emotional abuse.

Many non-profit organisations like Roshni in Britain advocate for and provide culturally sensitive support to British Desi women.

Research was done in 2018 by the University of Hull and the University of Roehampton which showed that sexual abuse reporting rates, in general, are low.

Yet, reporting is lower than expected within British South Asian communities.

Abuse, especially sexual abuse, remains a taboo topic.

For example, rape may be seen as the izzat (honour) of a woman/family being lost. If virginity is lost outside of marriage, even through violence, women are shamed, stigmatised, and ostracised.

It is also a cultural norm to try and resolve cases of abuse within the families rather than involve outsiders like the police.

Kalsoom Faheed*, a 32-year-old British Bangladeshi mother of three, states:

“When my husband hit me first, I thought his promise that it wouldn’t happen again would be kept. It wasn’t.

“When he hit me even more, and I was thinking of leaving, our families intervened. Both mine and his family persuaded me to try to work things out. They said they would mediate.

Kalsoom continues:

“Fathers are important for children they said. They would help me, they said. There’s no need for police, it would just cause a headache.

“It was all rot. It took me time to realise that it was important to say something. That I had to do something for me and my babies.”

Ideas of shame and cultural norms and ideals make it challenging for British Desi women to talk openly about abuse and take action.

The longstanding thought that many issues can be solved within Desi families should be questioned. Many communities see seeking help from others as a sign of weakness.

However, the significant tools needed to deal with things such as sexual abuse and even mental wellbeing are a necessity within this modern generation.

Cheating Partners & Cultural Expectations

Moving on, British Asian women can face is the cultural expectations to make things work when a spouse/partner cheats.

While some Desi women forgive and wish to work things out, others find themselves persuaded to do so and can be judged for walking away.

Due to misconceptions around male and female sexuality, a Desi woman cheating is culturally seen as more morally corrupt. A stain on the family honour.

Firdose Farman* a 34-year-old British Bangladeshi estate agent, states:

“I was cheated on two years ago, and so many of the elders said forgiveness is divine. They said everyone makes mistakes.

“When I said ‘what about if it had been me, a woman that had cheated’, the silence was deafening. The double standard is alive.”

Firdose then reveals:

“My parents and siblings had my back, and supported my decisions and right to follow my feelings.”

Also, Karamjit Bhogal*, a 26-year-old bank worker in Manchester, found herself frustrated with the double standards that exist:

“It’s ridiculous but when I told the family Manjit was cheating, my uncles said, ‘where’s your evidence?’.

“They said that if I left him without proof, Manjit and other people would judge. They would say I used cheating as an excuse to end things.”

She then points out:

“I know a family member whose husband thought she was cheating, wrongly, and made the mistake of opening his mouth to everyone.

“Even though she didn’t cheat and they’re together, people still whisper. The same whispering rarely happens when it’s the other way around.”

Cultural perceptions of cheating and the need for a good Desi woman to forgive, mean women continue to face challenges when they want to leave.

Nevertheless, the severity of the pressure to stay with a cheating spouse when a Desi woman does not want to has diminished. Unlike decades ago, when it would have been a fearfully shocking act.

Yet, a woman leaving a spouse is still frowned on so the question remains how progressive have British Asian communities really been?

Remarriage for British Desi Women

Moreover, some British Asian women are also challenged with navigating family and cultural judgments around getting remarried.

Also, whilst not all women who marry wish to have children, those who do, face criticism for having children from different spouses.

Reba Begum*, a 34-year-old Bangladeshi woman based in Sheffield, remarried four years ago:

“I remember my parents were happy about me getting remarried, they wanted more grandkids. But my dad’s older brother’s and grandfather’s eyebrows went up.

“I heard a conversation where my uncle said me remarrying was shameful. He was disgusted that I would have children who didn’t have the same father.

“Yet my uncle has been married three times, had kids each time, and had a son outside marriage and he barely does anything for them.”

This shows the shocking and unfair state of both genders within Desi households.

Minreet Kaur, 27 years old at the time of her BBC interview in 2019 feels as a divorcee, Sikh men do not consider her eligible for marriage.

The “man in charge of the Hounslow temple’s matrimonial service, Mr Grewal” told her:

“They (Sikh men and their parents) are not going to accept divorce, as it shouldn’t happen in the Sikh community if we follow the faith.”

Furthermore, at some of the temples, Minreet went to, she saw divorced Sikh men being introduced to potential Sikh brides who had not been married.

Nonetheless, the fact is some Sikhs do get divorced. The 2018 British Sikh Report says that 4% have been divorced and another 1% separated.

Yet from Minreet’s account, women are still judged more harshly. In her words, she expresses:

“One of my mum’s friends sons told us I was like a ‘scratched car’.”

The tensions that emerge when it comes to British Asian women remarrying shows the continued gender inequality that exists.

It also emphasises the tiresome journey of some British Asian women. Having to deal with their own career whilst finding a suitor and then stressing over how they’ll be seen if they get divorced.

All these elements are challenging but having to face them collectively undoubtedly needs addressing.

Navigating Single Parenthood

In 2021, single parenthood is more common. ONS showed in its 2020 data that 2.9 million single-parent families in the UK exist.

Moreover, a large proportion of single parents in Britain are women.

British Desi women, where the traditional nuclear family is idealised, can face challenges as single parents.

Lone mothers face financial strains and may have to take on the role of two parents. Additionally, they may have to deal with any emotional issues children have.

Likewise, working single mothers often rely on informal childcare methods, like their parents, aunts and friends.

These mothers may also have to endure taunts, criticisms and hurtful remarks about the dangers of single motherhood.

*Mobeen Sharif*, a 31-year-old British Bangladeshi mother to a toddler, states:

“My parents talk to everyone in the community, so when I became single with a baby, the gossip was ripe.

“I’ve become the cautionary tale told to some girls. People can give me pitying looks and make comments that annoy me.”

She proceeds to maintain:

“For some reason, they cannot believe that I am better of a single mother than a married woman.”

In turn, Sima Ahmed, a 45-year-old British Pakistani single mother, says:

“Being a first-generation single mum started as a nightmare. I could speak English but couldn’t write well.

She continues:

“My husband had dealt with all the bills, forms, everything. I didn’t understand the benefits system and how to get support.

“If not for a friend I would have been lost, all my family were in Pakistan.”

An interplay of forces like laws, bureaucracy, gendered ideologies of South Asian motherhood, patriarchy, and a capitalist economy all combine to marginalise British Desi single mothers further.

British Asian single mothers can gain agency, empowerment and independence but they face many restrictive hurdles which have such high risks if challenged but need to be disputed in order to evolve.

Elderly Responsibility

One key South Asian stereotype is that sons will be responsible for parents’ care once they reach adulthood.

Unfortunately, this is something many British Desi families still hold true and it can cause challenges for British Asian women.

This stereotype also can play a role in increasing the loneliness British Desi elderly people experience.

Decades ago, even whispers of sending Desi parents to care homes was shameful. However, British care homes focusing on the Desi elderly are growing.

Residential care homes like Aashna House in London provide culturally sensitive care to elderly South Asians. At Aashna House, all those employed come from South Asian backgrounds.

Elderly relatives being cared for within the family is something that Asians have taken great pride in.

Yet this very act of ‘caring’ within the home can be problematic, and it again highlights issues that can bring British women difficulties.

Yasmina Bilkis*, a 54-year-old British Pakistani office worker from Birmingham, has three brothers and one sister.

She has faced conflict over cultural ideas of who should care for unwell ageing parents.

She has also found herself questioning the legitimacy of the stereotype that sons, when older, should be the ones taking care of parents:

“My brothers have been making decisions about my parents care. My parents live with my eldest brother.

“The son and his family are meant to take care of parents when it is time. What no one mentions is that so-called care can be crap.”

She goes onto say:

“Me and my sister tried it the Asian way, and it didn’t work. So now we are fighting to do it our way.

“My brother is at work all day, and his wife doesn’t do what they said they would.”

For Yasmina, the traditional belief of Desi sons being responsible for elderly/sick parents can force Desi women like her into a corner.

A corner from which they watch decisions that can harm their parent, emotionally and physically.

Overall it is clear that British Desi women continue to face challenges in their daily lives.

Some of these challenges were surprisingly experienced by their mothers and grandmothers. Whilst other challenges are new, they still present the same concern for British Asian women.

The main aspect of dealing with these challenges is to raise more awareness in Desi communities. Not only will this attract more attention, but it will let British Asian women know that the support is there.

With taboo topics such as sex and mental health, there should be an encouragement to tackle the obstacles within these sectors.

Especially when factoring in how many organisations there are for women to explore to obtain some support.

Although the increase in female bloggers and influencers has enabled a sturdier platform for British Asian women to receive guidance.

This hopeful conquest should allow a change in South Asian households and highlight the need for quick action and effective change.