"War inflicts pain, but it can only be endured by love."

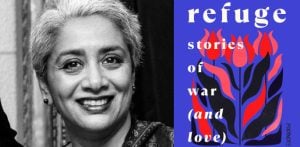

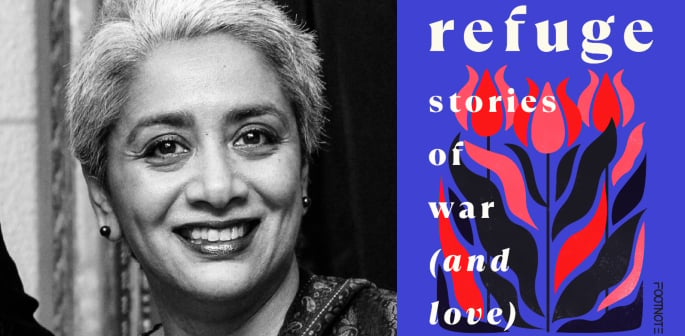

Spanning a century of conflicts and crossing continents, Refuge: Stories of War (and Love) by Sunny Singh offers an unflinching yet deeply humane exploration of survival, love, and memory.

Written over 25 years, the collection brings together narratives shaped by Singh’s own experiences as a ‘fauji brat’ and her lifelong engagement with questions of war, justice, and belonging.

In these stories, the usual heroes of battle step aside, making room for the women, civilians, and survivors whose voices are so often absent from mainstream war literature.

Singh’s lens is both intimate and expansive, revealing not just the brutality of violence but also the endurance, tenderness, and grace that help people navigate the unimaginable.

Drawing on the precision of the short story form and inspired by literary greats from Manto to Prem Chand, Singh crafts moments of startling beauty amid chaos.

From a soldier adorning herself in jewels before a mission to quiet gestures of love that defy despair, Refuge refuses to let humanity be eclipsed by destruction.

In this exclusive DESIblitz interview, Singh reflects on the decades-long journey to write the collection, the ethical considerations that shaped each story, and the conversations she hopes to spark within South Asian and diasporic communities.

Refuge spans continents and decades. What was the journey like in bringing these stories together after 25 years of planning?

I am what in India we call a ‘fauji brat.’

My father served in the Indian military, and in fact in all three branches: air force, navy and the army, which makes him very unusual.

My first novel came out just as he was about to retire.

I had perhaps a rather childish idea in my mind: I wanted to write stories about people I knew, admired and loved.

However, once I started researching my book, I began questioning how stories about war are written, who is made out to be the hero, and who gets to write them.

I also realised very quickly that I did not have the knowledge or ability to write the stories well at that time.

I also did not have the psychological and emotional capacity.

Most of all, I wanted to write these stories in an ethical way, in a human and humane way.

So I wrote these stories slowly and only tackled each one as my understanding and ability grew.

The first one was written almost 25 years ago and is set in the same cantonment town where I grew up.

Strangely enough, the process became a full circle: the last story I wrote for the collection is again set in that same cantonment town, with some of the same characters.

It felt right to end the collection where I started: in my home, in the Himalayas.

The collection centres those often left out of mainstream war narratives. Why was it important for you to highlight these voices?

My first memories date back to the 1971 war, but they are not of heroic soldiers being brave in battle.

My first memories date back to the 1971 war, but they are not of heroic soldiers being brave in battle.

Mine are about scary nights of blackouts against air raids, of my mother and other army wives waiting anxiously for news while also trying to support each other and our families.

Most of all, I remember my mother’s relief when my father returned, along with my childish confusion and sadness that so many people I knew did not come back.

When I began reading research and literature about war, I realised that most stories are about men who go off to war.

They either come back as heroes or die heroically. Even then, most stories don’t really focus on the terrible things they do while at war.

Yet the brunt of war, the worst of mass violence, is always borne by women, children, and civilians.

I really believe that if we stop glorifying those who are sent to implement violence and start listening to those who are forced to bear that violence, we would think differently about war.

And this includes listening to soldiers, not in the simplistic way to glorify ‘our boys’ as brave heroes, but as humans who are injured physically, psychologically, morally by war.

What drew you to the short story form for this project, and how did that shape the way each narrative unfolds?

I have long been fascinated by the short story as a form. To me, it feels like the most difficult of forms as it requires such precision.

As a novelist, I know I can indulge myself in sentences, even entire paragraphs, that may not necessarily serve the storytelling.

But for the short story, every word counts. I think of it as a challenge, a dare, to myself: can I do this? And do it well?

However, there is another side: my first language is Hindustani.

When I was a child, there was a magazine called Dharmayug which carried works by India’s finest writers.

“Given the magazine format, this means either short stories or serialised novels.”

Every time a new issue arrived, there was a scramble amongst the adults in my family to read it first.

By the evening, things would calm down, and when we gathered for dinner, the adults would take turns reading out the stories.

So I learned about the short story as a form and fell in love with it very early.

I chose that same form to pay homage to writers I love and admire even now, ranging from Chandradhar Sharma Guleri (often considered the writer of the first Hindi short story), Prem Chand, Saadat Hasan Manto and more.

War is often associated with brutality, but Refuge explores themes of love and endurance. How did you strike that emotional balance across the collection?

I think we should realise that war causes loss, war inflicts pain, but it can only be endured by love.

I think we should realise that war causes loss, war inflicts pain, but it can only be endured by love.

My collection recognises the brutality of war, but I am fascinated, even awed, by how we endure the intolerable horror of war.

That endurance is because of love and not just romantic love.

It is for ourselves, our families, friends, communities, but also greater ideals like freedom and justice.

It is so extraordinary that we humans can love like this even as we do the worst things to each other.

The stories in Refuge are set against the backdrop of a century of wars, but really, at its heart, it is a book about love.

One of the stories features a soldier adorning herself in jewels before a mission. Can you talk us through the symbolism behind moments like these in the book?

South Asia has a long tradition of women warriors. There were many women who led and fought in the 1857 Uprising, for example.

The Azad Hind Fauj, led by Subhash Chandra Bose, had an all-women combat regiment named after the Rani of Jhansi.

Today, women serve in major South Asian militaries and most of the non-state armed organisations.

I am fascinated by how gender norms vary by culture and how they impact women, even when they go to war.

Srngara, deliberate adornment, is so crucial to South Asian practices and rituals of femininity.

At the same time, we get the big Hollywood war films, think Rambo, for example, where (mostly) male soldiers are shown ‘gearing up’ before battle.

In the instance you mention, I wanted to explore what adorning oneself in silks and jewels as ‘gearing up’ could mean to a woman soldier and what it can say about her history, her culture, her past and motivations.

With your work in decolonisation and the Jhalak Prize, how does Refuge fit into your mission as a writer and public intellectual?

My work as an anti-colonial academic and as the director of the Jhalak Prize is based on the understanding that we need to tell and hear a much greater range of stories.

My work as an anti-colonial academic and as the director of the Jhalak Prize is based on the understanding that we need to tell and hear a much greater range of stories.

Refuge is part of that same mission and ideal: to tell stories of people who don’t often show up in stories as full human beings.

When we only create and consume stories by and about a small group of people, we don’t learn or understand vast parts of our world and each other.

“Stories are how we learn from each other. Stories are how we make sense of our world.”

Stories are how we build and break relationships, how we make friends and enemies, and learn to love and hate.

It is very difficult to other, dehumanise and demonise anyone once you learn their story.

It is harder to hate, exploit and do violence to people when we know their stories.

So to me, Jhalak Prize, my own writing, including Refuge, my work as a public intellectual, are part of the same work: of telling, sharing, celebrating as great a range of stories as possible.

What conversations do you hope Refuge sparks among readers, particularly within the South Asian and diasporic communities?

The formation of South Asian nation-states in 1947 left the subcontinent with a constant process of othering and demonisation of each other.

And all these are necessary to carry out war and brutality.

The hardest part of writing Refuge was to find ways of not demonising even those who do the most horrific things to fellow humans.

We must see each other’s humanity in all its horror and all its beauty. That is the only way we can find ways to co-exist.

Given that we only have one planet and we must learn to live on it, there is no other choice but co-existence.

I hope Refuge gets us thinking and talking about how to reach out across differences, unlearn what we have been taught about each other, and learn to co-exist.

I know that is a big dream… but we have to try.

You’re set to appear at several festivals this year. What are you most looking forward to as Refuge reaches readers?

The stories in Refuge are about how humans endure and resist even in the most horrific circumstances.

The stories in Refuge are about how humans endure and resist even in the most horrific circumstances.

To me, this is the most beautiful, graceful aspect of our humanity.

It is important that we remember that we are witnessing three simultaneous genocides right now, along with horrific levels of mass violence by multiple states across the world.

Yet in each instance, there are extraordinary stories of daily, quiet, enduring love.

If we look again at the people enduring war, we will witness this grace, this love.

I hope those who come to any of my events and/or read Refuge, will remember that we not only have the capacity for brutality, but we also have the ability for infinite, powerful love.

Refuge: Stories of War (and Love) is as much a testament to the power of love as it is a record of human endurance.

Sunny Singh’s characters bear witness to loss and violence, but also to the resilience, dignity, and connection that survive in their wake.

By centring voices historically sidelined in war narratives, Singh challenges readers to confront entrenched myths and to consider war from the perspective of those who endure it rather than those who wage it.

Her work here is both literary and political, an act of storytelling that refuses to dehumanise, even in the face of horror.

It is a call to empathy, to dialogue, and ultimately, to co-existence.

As Singh continues to share Refuge at literary festivals and beyond, the hope is that these stories will travel as widely as the conflicts they depict, reminding readers that even in the darkest times, love can be as enduring as war.