“From the time my periods started, I was indirectly told to hide it."

Period poverty exists around the world. In India, managing your period without proper menstrual hygiene facilities and safe sanitary products is especially challenging.

Millions of girls do not have access to sanitary products, support and education in regards to menstruation.

Girls in India may miss school during their period or drop out entirely as a result of period poverty.

As menstruation is still seen as a taboo in India, many girls find themselves unsure about sanitary products and how to use them.

The hefty cost and lack of access associated with period products is something that many Indian policymakers refuse to acknowledge.

Alongside the lack of availability of period products and cleaning facilities, waste management also needs to be addressed.

It is also important to acknowledge that not all women menstruate. This could be due to various medical conditions as well as the issue of the gender binary.

Effect of Period Poverty

Menstruation in India is still considered impure and unclean.

Whilst on her period, an Indian girl may be subjected to sleeping outside her home and wearing the same clothes.

She may also be forced to isolate herself from her family during her period as menstruation is considered dirty.

In many areas, when a girl is menstruating, she will not be permitted to enter places of worship and her dignity may be questioned.

These religious practices reinforce the cultural shame surrounding menstruation in India and prohibit the progress of achieving menstrual equity.

The accessibility of menstrual hygiene products is incredibly low as a result of Covid-19.

Covid-19 has led to an increase in period poverty around the world – especially in India. According to the Indian Ministry of Health, 88% of menstruators depend on unsafe materials to manage their period.

In third world countries (including India), health conditions such as malnutrition can severely impact menstruation.

Many girls in India have no choice but to resort to finding and making products to manage their menstruation.

Rags, cloths, sawdust, sand and hay are commonly used by Indian girls in place of sanitary pads and towels.

This is particularly harmful as it can lead to life-threatening infections. These include urinary tract infection (UTI), vaginal itching, white and green discharge and bacterial vaginosis.

Girls with special needs and disabilities also suffer immensely as they do not have access to the amenities they require during menstruation.

To cope with their periods, Indian women may resort to harmful coping mechanisms such as transactional sex to pay for their period products. This is especially common for schoolgirls in Kenya.

A 2019 report by the University of Leeds Nuffield Centre for International Health and Development revealed that without access to toilets, women and girls in third world countries purposely eat and drink less during their period to avoid poor sanitisation facilities.

The stigma has negative effects on mental health. It can disempower girls, leading them to feel self-conscious and uncomfortable about the biological process.

Impact on Education

For many Indian students, missing school while menstruating has become the norm.

Students may resort to skipping school during their period due to the social stigma, shame, isolation and the lack of accessibility of products.

The drop-out rate of girls from school rises as they reach puberty and their menstrual cycle begins.

Dropping out of school can inevitably lead to a stunted education and a much lower chance of attaining a good career in the future.

Young girls who do not receive an education are also much more likely to be forced into child marriages, suffer from malnourishment and have pregnancy complications.

DESIblitz exclusively chats to Navia Meena, who grew up in India and has first-hand experience with period poverty. She said:

“I remember starting my first period at school and my teacher pulled me to the side and told me that my uniform was stained.

“My father picked me up and I felt so embarrassed. We didn’t say a word to each other in the car ride home.

“I had to use these makeshift ‘pads’ as a teenager that my mother made out of cloths because we didn’t have access to anything better.”

In India, boys are often not taught about menstruation. This heightens the sense of embarrassment for girls and can lead to bullying around ‘period shame’.

As for girls, menstruation is taught in schools, however, discussions are unlikely to happen at home or even in school after the lesson due to cultural norms.

As a result, young girls may feel ostracised and the lack of communication reinforces the sense of silencing around such issues.

Many government schools in India lack separate toilets for girls and the availability of sanitary products is low.

A lack of access to period products in schools also reinforces the fact that these products are viewed as ‘luxury’ items and not essential.

The number of female teachers, especially in more remote areas and villages, is low compared to their male counterparts.

Kuwali Sarma also shares her experience:

“From the time my periods started, I was indirectly told to hide it. I was told I wasn’t allowed to visit a temple whilst I was menstruating.

“I would lie that I had a cold or fever every time I missed school or tuition because I was discouraged to talk about periods to my guy friends.

“One of my classmates once asked our biology teacher about menstruation and everyone started giggling. The teacher refused to explain it and asked him to read the chapter on reproduction.”

How to Tackle Period Poverty

To tackle the issue of period poverty, the first step is to take part in conversations.

Talking about periods will help to normalise them and create a dialogue that will help to reduce the stigma.

Educating both boys and girls about menstruation can help to break the stigma.

Girls are entitled to factual information regarding the various period product options available so that they can make an empowered choice.

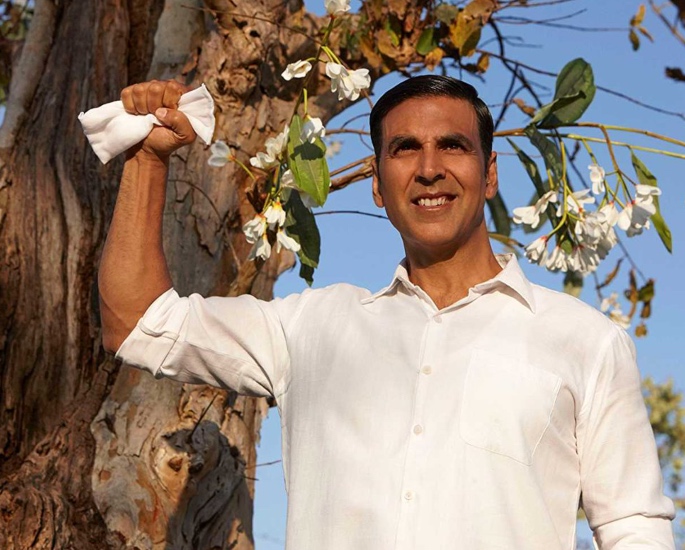

The Bollywood film, Pad Man (2018), raised awareness of the period stigma in society and has helped to start the necessary conversation in India.

The next and most crucial step is the enforcement of policies to make menstrual products and hygiene easily accessible to all.

Sanjay Wijesekera, former UNICEF Chief of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene says:

“Meeting the hygiene needs of all adolescent girls is a fundamental issue of human rights, dignity, and public health.”

Activists and menstrual health advocates are helping to make a change by reminding governments around the world that menstrual products need to be viewed as essential commodities.

Free Periods, a not for profit organisation founded by Amika George, campaigned for policy changes in 2019.

In January 2020, the Government committed funding for free period products in schools in England.

In India, the social enterprise She Wings actively works to eradicate period poverty in the country.

She Wings co-founder Madan Mohit Bhardwaj says:

“In most Western countries, the population is looked after in some way or the other by the government.

“In a developing country like India, the population is so huge that government facilities can’t cover it. The lack of education and affordability of sanitary products is another factor.”

In July 2018, India removed its 12% tax on sanitary products to make them more accessible to everyone. This was achieved following months of campaigning by activists.

Whilst period poverty is very much a global issue, the situation in India seems to be at another level.

Sharing stories and education around menstrual hygiene is vital for an India that is free of the period taboo.

Until change takes place, period poverty (as well as the social stigma and taboo) will continually lead to more school absences in India.