"Going back to Africa, they said I can't go back"

Despite East African Asians establishing themselves between the 1940-1960s, they began encountering various issues.

Leading up to the independence, and after Asians living in Kenya and Uganda were in somewhat of a dilemma.

Many had to decide between retaining their British citizenship or surrendering it for Kenyan or Ugandan nationality.

Others such as non-British passport holders were forced in making the move to the west.

In 1962, the Commonwealth Immigrants Act was also an early indicator that Asian civilisation was under threat in Africa.

Some of the Asians who remained in Africa were suffering from racial and discriminatory treatment under new African regimes.

In addition, the Africanisation programme, particularly in Kenya, had a huge bearing on Asians, marginalising them in many different ways

The growth of Kenyanisation policies saw Africans becoming more dominant in the economy and society.

We take a closer look at the impact of independence and Africanisation on South Asians from Kenya and Uganda.

Pre-Independence

Before attaining independence between 1962-1963, the number of East African Asians living in Kenya and Uganda varied.

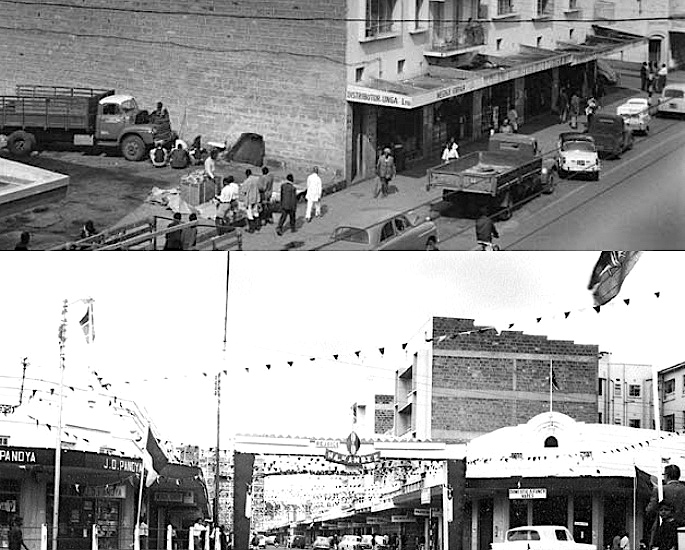

Many South Asians in Kenya had prosperous businesses or good jobs in a range of government or non-governmental sectors including construction, engineering, railways and so forth.

Despite holding the middle position, of the 2% Asian population in Kenya, some were making a massive contribution to the economic structure.

Their dominance on the main street was equating to one-third of Nairobi’s population.

Asians were owning almost three-quarters of the private non-farming assets in Kenya before independence.

They were also discreetly financing emerging nationalist political parties. These include KADU (Kenya African Democratic Union) and KANU (Kenya African National Union).

The situation was slightly different in Uganda in that resentment and Indophopia was on the rise, with South Asians being very prosperous and dominating the Ugandan economy.

Therefore, most Asians who had come from an undivided India and were British citizens by default wanted to remain in East Africa. They felt comfortable in East Africa, especially with their ready-made success.

But it was a different story for those who had come to Kenya or Uganda post-partition of India. Many of them made the move to the UK, in the few years leading up to independence.

One of them was former Birmingham businessman Muhammad Shafi. He had gone to Kenya in 1956, upon receiving a work permit invitation from his maternal uncle Abdul Rahman.

After travelling on the Karanja ship from Karachi, Pakistan to Mombasa he worked at the famous Coronation Hotel on River Road, Nairobi.

His work permit was renewed every six months until 1958 when it could not be extended any further.

With the help of a senior rank official at the Pakistan High Commission, his Pakistani passport was endorsed for the UK. A year later he, became a British citizen.

There were many other South Asians in a similar situation, emigrating to the likes of Canada and Britain.

Meanwhile, the emerging Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962 was causing further confusion for South Asians in East Africa. This particular act came into effect on July 1, 1962.

The 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act subjected Commonwealth citizens to immigration controls for the first time.

It initially stated that British passport holders living in independent Commonwealth countries will have the right of entry to Britain.

Without the exception of those who were studying abroad, most East African Asians who had a British passport chose to stay in Kenya and Uganda.

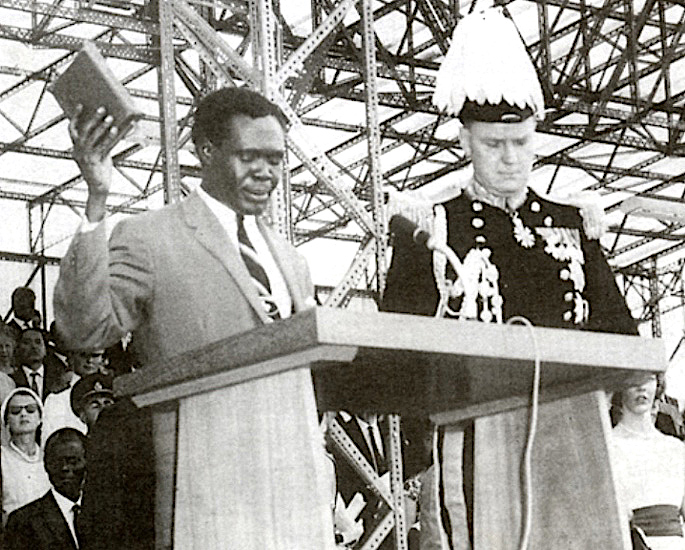

Independence and the Aftermath

On October 9, 1962, Uganda became independent. A year later, Kenya achieved freedom on December 12, 1963.

The independence saw major changes in the region, creating a somewhat volatile period between Africans and Asians.

According to the Daily Nation, 180,000 East African Asians were present during the independence of Kenya – three times more than non-Asian British people.

With Kenya becoming independent from Britain, the new Kenyan government gave East African Asians until December 1965 to decide their civilian status.

Many Asians preserved their British citizenship. In maintaining a British passport, they were believing it was a place of safety or refuge.

Having said that only a few East African Asians took the option of moving to Britain than expected straight away. Although, elements of the Kenyatta government had thought of expelling or deporting them.

The animosity and distrust between Africans and Asians grew further over time still. The local Africans felt the Asians were disloyal for not taking up Kenyan nationality.

Certain members from the Coronation Builders business and the Noordin family did surrender their British passports, acquiring Kenyan citizenship.

Salim Manji, a managing director of a large food manufacturing company spoke to the Christian Science Monitor about staying in Kenya:

“There is no fallback position and none is sought. Ours is a long-term commitment in terms of generations.”

Parminder Singh Bhogal from Model Builders in Smethwick, West Midlands who had left for the UK before the independence did not have good memories of Africa.

He told DESIblitz about being denied access to visit his family in Africa:

“Going back to Africa, they said I can’t go back – because I just came back after Independence. I can go there and visit my parents but I can’t stay there.”

“My parents were there already and they had a firm there, a building contractor firm there. So I just stuck here [Britain].

“I did not take it very well because I was born there and they rejected me… because they did not want me.

“So when I came to this country, I said to myself, ‘British people are better because I was not born here.’ All I had was a British passport and they accepted me. They gave me everything here.”

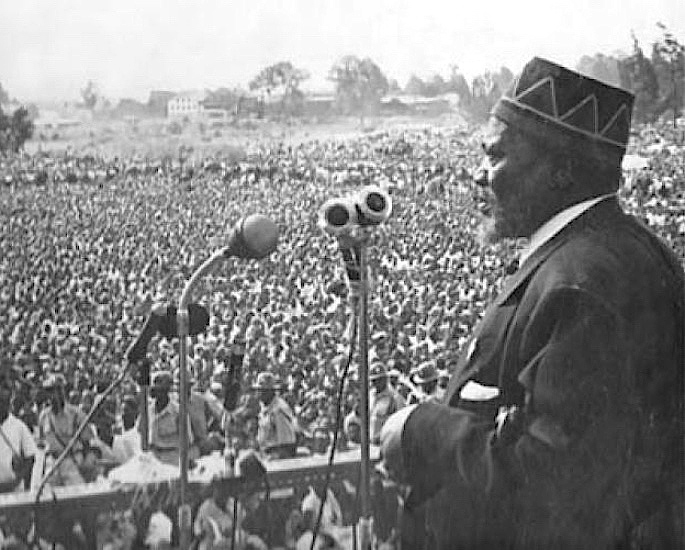

Dr Rose Duggal, Director of Crownsway Insurance Brokers Ltd exclusively tells us about Africans coming to the realisation of independence:

“It was when it became independent, the African people understood and got more knowledge that Africa actually belongs to Africans. And not the Asians and not the Whites.

“Hence, they claimed the country, Uhuru.”

After all the country was in the hands of the Africans, roles had reversed and a sense of selfishness began to emerge.

In Uganda, whilst a few may have come to the UK, most Ugandan Asians kept on staying in the country prior to the dictatorial Idi Amin revolution.

But out of the 80,000 Ugandan Asians, 50,000 made the decision to opt for British citizenship.

Africanisation and Unemployment

Following the independence in Kenya and Uganda, many Asians, particularly those without citizenship were subject to discrimination.

This was certainly the case in Kenya, under the Jomo Kenyatta led government. Life for Asians that did not relinquish their British passports became even more difficult.

In 1964, Kenya went onto adopt and introduce Africanisation policies, with citizens replacing non-citizens across key sectors of the economy and government. This gave the local black population more control.

Hence, some Asians became economically and socially marginalised. The introduction of Africanisation policies saw a major increase in unemployment for Asians.

Dr Sarindar Singh Sahota speaking about this exclusively mentions to DESIblitz:

‘Most of the people from the Asian community who were in employment were being made redundant.”

Asians had restrictions when it came to the choice of residence, trade and employment. Trade-in commodities such as necessary food were restricted to Africans only.

As a result, this was causing conflict between Africans, Asians and British people. Despite being largely responsible for a healthy East African economy, Asians were becoming less favourable when it came to employment.

Through wanting to work, South Asians found themselves in a difficult situation. Even though they were owning properties and businesses, there was a potential risk of losing it all.

Whilst some were fortunate to leave, those without citizenship that remained in Kenya were struggling.

With the Kenyan Immigration Act 1967, coming into effect, it went from a British perspective to a fresh Kenya way of life. Asians were denied work permits and licenses to trade.

They were looted, mugged and even had to give a share of their business to the Africans. In some instances, they had to hand over their businesses and move elsewhere if asked by the Africans.

In those days, Asians who kept their British citizenship were fearing that failure to comply with the Africans could mean facing deportation.

Talking to DESIbliz, Dhiren Patel, Director of Milan Sweet Centre in Birmingham highlighted the consequences of new rules:

“It all started changing when people went to work. These African people who used to work as servants they knew in and out of the house because all the families worked all year round.

“And suddenly they used to rob the house. Even kill the woman in the house.

“We used to call it Panga (African balded tool) gang. They used to have a big axe, and kill. And then they used to run away. There was a lot of fear.

“We were going to stay there. But in the end, we found out that life would be very difficult later on.”

The situation was similar in Uganda too, with president Milton Obote pursuing an Africanisation policy during his first term, targeting Ugandan Asians.

Additionally, Asians were referred to as dukawallas (shopkeepers), an occupational term that became a racial slur.

Consequently, towards the end of the 60s, many East African Asians began thinking of migrating to the UK, with some already making the move.

The East African Asians who had more privileges, were investing in their companies and small general grocery shops, which they ran as family businesses.

Interestingly, this was offering a new lease of life to the traditional community corner shop in large cities, like Nairobi in Kenya.

Other Asians deciding to stay in Kenya and Uganda, were studying and working hard, particularly young adults.

They also saved capital with the hope of investing across manufacturing and trading businesses in the future.

Watch the repatriation of working Asians after Africanisation here:

Leaving or remaining in East Africa during the 60s was certainly life-changing for many South Asians.

Equally, the transition and shift of power from the British to Africanisation policies were challenging.

Despite the difficulties East African Asians were facing, most of them, particularly those with successful businesses were operating as normal

East African Asians were known for their resilience, embracing their work and bravery in the 20th century.