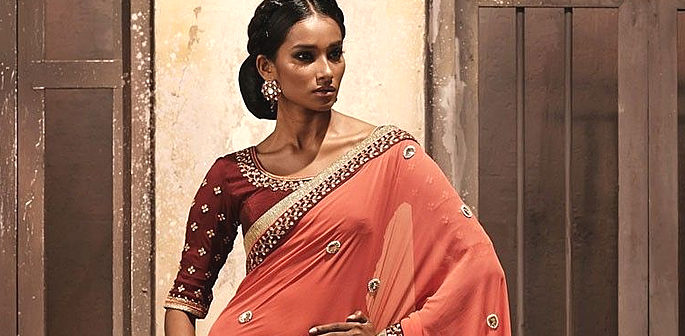

“The saree holds a special place within this code of eroticism.”

The saree or sari is an iconic Indian garment. The Indian saree is the most versatile and dynamic of garments. The fabric ranging between 5 and 9 yards is one of the oldest items of clothing still in use.

Throughout history, it has been proven that the fashion world is highly fluid. What was considered fashionable during the 1960s or even in the early 2000s is no longer considered fashionable in modern society.

Fashion is a field that is relentlessly inventing and reinventing itself. Despite this, the iconic saree has withstood the test of time.

India is a diverse country that has numerous dialects, traditions and cultures. However, the saree is still widely worn throughout the whole of India and by the South Asian diaspora worldwide.

The saree has endured two centuries of disruptions caused by industrialisation and colonialism and the turbulence brought by new conquers.

The traditional dress has continued to remain a ‘salient part’ of Indian women’s lives, even with the introduction of western clothes and the salwar kameez.

Traditional dress has commonly been viewed as static ritualised clothing of non-western countries, however, the mesmerising saree is anything but static.

Despite the saree being a ‘salient part’ of women’s lives for centuries, it has reinvented itself while keeping a close connection to tradition.

It is a true cultural icon that has a significance that stretches much further than simply its use as clothing.

Within Mukulika Banerjee and Daniel Miller’s book The Sari (2003) they express how the sari is not simply a piece of clothing, but rather “a lived garment”. It is a garment with a story.

We explore Banerjee and Miller’s comment in more depth, particularly exploring the significance of the sari. We will be looking at how the saree is a “lived garment” and the various stories it tells.

Indian Identity

The saree is centuries old; its origins can be traced to the Indus Valley civilisation in 1500 BC. Within Martand Singh’s book, Saris: Tradition and Beyond (2013), he expressed:

“The unstitched cloth is a truly Indian phenomenon.”

Clothing plays an integral role in the identity construction of regions, families, individuals and nations.

Clothes are the “extensions of the people that wear them”. They are just as vital a marker of an individual’s nationality as a native language would be.

In Bonnie Zare and Afsar Mohammed’s 2013 article about the sari, they maintained:

“Geographic places often become marked through dress. Just as Scotland is known for the kilt and the Western US for the cowboy hat, India and Indian women are commonly represented as a figure draped in a sari.”

Often when one thinks of India, images of a woman wearing a saree are brought to mind. The saree is a “quintessential Indian female garment”.

Academic, Dorothy Jones in her article ‘The Eloquent Sari’ explained:

“In India, cloth and clothing were profoundly implicated in colonialism and nationalist resistance as the British forcefully promoted their own textile industries at the expense of those in the country they governed.”

Following India’s independence in 1947, more emphasis was placed on the revival of the local textile heritage, as an assertion of national identity.

When India became a nation, the charka spinning wheel was placed on the centre of the flag. This depicts how homegrown textiles are ‘central to the nation’s consciousness’; it became a symbol of patriotism.

Linda Lynton, a scholar of Indian textiles and ethnic art, said in her 1995 book:

“Nothing identifies a woman as being Indian so strongly as the sari.”

In western societies, there are rarely any garments that are worn religiously by the majority of the population.

However, despite India being full of different religions and cultures, the saree is a unifying garment for all Indian women.

In 2017, Liz Mount carried out a study in which she interviewed urban middle-class women in Delhi, Mumbai and Pune. Mount’s aim was to assess the saree’s meaning to contemporary Indian women.

Most of the women Mount interviewed made associations with Indian identity and saree wearing. Mount asserted:

“Many [women] alluded to how wearing a sari makes them feel Indian in a way that wearing other types of clothing does not.”

In particular, one North Indian woman Mount interviewed expressed that for her, wearing a saree is:

“A tradition which you need to continue. It’s part of who you are, where you came from…India is what I wear and how I portray myself and what I look like.”

Another woman stated how she deliberately wears sarees when travelling out of India.

This highlights how these women, within Mount’s study, feel they are representing India when wearing a saree.

What was most intriguing about these comments is that the women in Mounts study are in their early thirties. This shows how the saree is a distinct part of Indian national identity even for the modern generations.

The sari truly is a “lived garment”. It is more than just an item of clothing, but rather is an emblem of India.

Traditional Cultural Identity

The saree is not just a garment, it is inherently ingrained with traditional cultural codes surrounding respectable married women.

While the clothes one wears does crystalise their identity, clothing also illuminates the values of the society and culture they were made in.

The saree is simultaneously a sign of traditional Indian values.

Traditionally, a woman’s body is viewed as the fragile container of not only her own reputation but also her families respect and credibility within the community.

Cultural notions of Izzat (honour) and modesty traditionally hold a great deal of importance within Indian culture.

Therefore, there has been strong cultural expectations surrounding what is appropriate for married women to wear.

The saree has traditionally been seen as ‘fulfilling all the requirements of modesty’ and is expected to be worn after marriage.

Banerjee and Miller’s study follows the story of Mina, a married Indian woman, and her relationship with her saree.

Mina mentioned how prior to her wedding she had never worn a saree, but after marriage, she has worn it constantly. Once when Mina was wearing a salwar kameez, her husband told her to change and expressed:

“I want a wife by my side, not a girlfriend.”

Mina further asserted:

“So, I don’t have a choice about wearing sarees, I have to.”

Due to the Indian cultural norms surrounding modesty, Mina mentioned how she “lives in constant fear” of letting her saree slip off her head or unravelling in the company of her male in-laws.

Banerjee and Miller mentioned how:

“She [Mina] can hardly sleep because she is so afraid that loss of consciousness will lead to her head or knees being uncovered and as a result, she feels stifled in the summer nights.”

The versatile garment is not just a representation of national identity, but also for some has traditional cultural norms weaved into it.

It truly is a “lived garment”, occupying different ‘lives’ in a sense.

The Professional Saree

Singh, in his book about the saree, maintained:

“The comfort and practicality of the sari make it an ideal garment for working women in all spheres.”

He continued: “Over the years working women regardless of cast or community have adopted the sari to meet the demands of their profession.”

The garment is also used by many as a practical working attire across India. The garment in particular holds a significant place in the corporate world.

Within Alison Lurie’s study on clothes (1992), she mentions how:

“Fashion is too a language of signs, a non-verbal system of communication.”

The spoken word can have alternate meanings for different people depending on the modifications of the verbs, nouns and punctuation in the sentence.

Similarly, clothing can also be interpreted differently when similar modifications are made to an outfit. If slight modifications are made to the saree’s fabric or draping style, the whole meaning of the outfit is altered.

Also, the context in which the sari is worn can change the power the saree holds. It is truly a dynamic garment.

In particular, the Nivi style of sari drape has become an aspirational symbol of power dressing among working women.

The Nivi style of saree drape involves wrapping the fabric around the lower body, pleating and tucking it into the petticoat. The loose fabric is then draped over one shoulder.

Academic, Rachel Dwyer, claimed: “The Nivi style has come to be regarded as the national dress of the Indian woman.”

The Nivi style has emerged as a popular style for young urban middle-class Indian working women.

A part of the saris charm lies in the fact that one 9-yard piece of cloth can embody multiple meanings. Mount, when talking on the many meanings the sari possesses, asserted:

“The garment remains strongly associated with respect and maturity for women, within their families, but also in the public sphere and in the workplace.”

One Indian lecturer, interviewed in Mount’s 2017 study, reiterates this power of the saree, by maintaining:

“If you wear a sari you get a lot more respect and they will listen to you… the sari holds better for working women.”

Further asserting:

“It is a sign of age or power, a sign of maturity, the sari becomes the symbol. They listen to you because you are a mature person like you listen to your parents. The sari still holds a lot of weightage and respect.”

Similarly, an art lecturer, interviewed by Mount, stated how within the academic environment wearing the saree alters how you are perceived.

She explained how on her first day when she walked in wearing western clothes, she overheard her students saying: “there’s a new admission let’s rag her”.

The saree is not just a sign of Indian identity, but also an emblem of authority and power for the modern working Indian woman.

Traditionally, it is a marker of maternal respect, however, it can also be used as a strategic weapon within the workplace.

Banerjee and Miller express that nowadays:

“Young urban women debate the merits of whether saris are practical garb for riding scooters to the office, where even a generation ago working women were frowned upon.”

Banerjee and Miller note how a hot topic of discussion among young women is which styles of sari are most practical for working in.

While a generation ago even the very idea of a young Indian woman working outside the home was inherently ‘frowned upon’.

For something to be living it would mean it has a life and is continually progressing forward. This is essentially what the sari is doing, it has progressed and adapted itself to the modern world.

It is not just a static traditional garment of the past but has evolved into a modern garment. As the women in Mount’s study mentioned, the sari is worn as a powerful tool in the professional world.

It truly is a “lived garment”. The sari has adjusted to modern life and has incorporated itself into modern twenty-first century Indian identity, despite the growing popularity of western clothing.

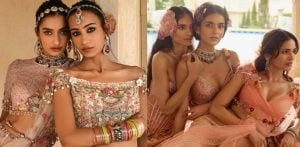

A Garment for Everyone

There are rarely any items of clothing that are worn by women of different classes and ages; however, the sari is a different case.

Singh, within his book about the saree, stated that: “There is in fact no one type of sari.”

He added: “The lady from the fishing community wears it differently from say the rice planting lady. An urban woman from Gujarat wears it differently from the woman of Tamil Nadu.”

The saree is a garment that transcends cultural differences, social class and generational gaps. It is a garment that works for every woman, once slight modifications are made to the fabric, style and colour.

The 9-yard piece of fabric can be worn in 108 different ways. The changes in draping style are down to the age of the wearer and cultural traditions of the area they are from.

One woman, interviewed within Banerjee and Miller’s study, told the story of how her mother used to help wrap her sari and she was laughed at by her peers because:

“My mother wore her sari like an old woman, she did not know how to put it on for me fashionably.”

The saree is suitable for both old and young women, depending on the draping style.

There are also ‘strong cultural connections’ associated with the colour of the sari.

Young women are expected to wear bright colours that represent joy. White is considered to be the colour of mourning for the widow and darker colours are more respectable for older women.

The sari is suitable for women of any age and class, just by making slight variations in the style, colour and fabric.

In western society, there are rarely any items of clothing which are worn simultaneously by the upper classes and lower classes. However, the sari transcends social class and can be worn by all women.

Be it working in the fields or in an office or attending a formal party or wedding – the sari is a garment for all women. It is a “lived garment” that transforms itself according to its function and need.

A Lifelong Companion

The sari is an integral component in an Indian woman’s life-cycle as a whole. It is a garment that essentially “grows” with you.

One coherent theme among the academic literature exploring the sari is that the act of wearing a sari constitutes as a relationship.

Wearing a sari is not just presented as a passive act of wearing clothes. It is often viewed as a “ceremonial rite of passage” in a woman’s life.

Wearing the sari is an all-encompassing connection throughout your life that cannot be easily broken.

Slight alterations made to the colour, fabric and drape of the sari mark psychological and physical stages within your life-cycle.

Saree’s are often worn at weddings or when attending the school farewell ceremony, when meeting in-laws and subsequently after.

However, often an individual’s first experience of a sari is through their mother. Banerjee and Miller, when talking on the sari’s role at different points within a woman’s life, express that:

“Mothers use it as a multipurpose nursing tool. When breastfeeding they cradle the baby within it, veiling the operation from the outside world.”

Mina, the woman referred to within Banerjee and Miller’s study, explains how her son “learnt to walk holding not my finger, but my pallu.”

Banerjee and Miller make the analogy of learning how to wear a sari is akin to learning how to drive, further mentioning that:

“Learning to drive and learning to wear a sari both mark a shift in one’s sense of age.”

Learning how to drive is often considered to be a key milestone in one’s life, it ‘mark’s a shift in one’s own sense of age’. It is a key marker in the gradual process of moving from a teenager to an adult.

The fact Miller compares wearing a sari as a similar milestone to learning to drive accentuates how the sari is a ‘ceremonial rite of passage’.

It is a garment that does not just crystalise your identity but is integrated into an Indian woman’s life-cycle.

The sari is almost a woman’s second-skin, experiencing key life moments with her. It is not just a garment you wear, but a physical marker of your stage in life.

The sari truly is a “lived garment”. It progresses with an Indian woman through her life and is just as much as part of her youth, marriage and career as she is.

The Erotic Saree

Within Clare Wilkinson-Weber book Fashioning Bollywood: The Making and Meaning of Hindi Film Costume (2013), she expresses:

“There is a stubborn association of western clothes with vulgarity and exposure.”

Further maintaining:

“Even the sari, the otherwise thoroughly respectable dress of the adult married woman, is as readily associated with emotion and intimacy as it is with status and power.

Its erotic potential emerges from its essential character as a sinuous wrapping of the body.”

Considering this, the saree does not just tell a national, cultural, traditional or modern story, but also an erotic one. The sari holds particular significance as an erotic fashion garment within Hindi movies.

India has a long history with regards to sexuality and eroticism. In particular, India has a well-known ancient erotic tradition known as Kama Sutra.

Kama Sutra is commonly thought to be just a manual on sex positions. However, it is an ancient Sanskrit text, that is in fact about the art of living a pleasurable life.

It contains information on emotional fulfilment in life, as well as sexuality and eroticism.

Aside from Kama Sutra, India has played a major role in shaping understandings around sexuality.

In particular, in ancient times erotic art, such as sculptures, paintings and literature were used to shape attitudes towards sex.

The idealised female body is mentioned within ancient texts and seen frequently in ancient carvings.

Dwyer, in her 2000 article discussing the saris use within Hindi films, mentions that these ancient art forms:

“While concentrating on depictions of the idealised female body, at no time do we find an obsession with the nude.”

Much of the ancient Indian texts and art did explicitly talk about sex and the female body, but nudity featured very rarely.

Within traditional South Asian culture, female nudity is viewed as bringing disgrace and shame on her family.

In align with this and ancient Indian eroticism, Hindi filmmakers have developed their own codes of eroticism and femininity. In particular, the sari holds a special place within this code of eroticism.

While the sari is considered to be a traditional and modest form of daily and professional dress, sensualism is also a crucial part of the sari’s semantics.

The saree allows you to cover up, showing a minimal amount of skin, but also accentuates the wearer’s curves.

Often within Hindi films, the heroine has an “idealised female body” of a small waist and full breasts and hips.

Dwyer reiterates this by expressing:

“The sari is the perfect garment to accentuate this body. It’s drape drawing attention to the acceptable erotic zones of the breasts, waist and hips while covering them which conceals the shape of the legs.”

Further maintaining:

“It allows the display of the female body associated with fertility and maternity, while simultaneously revealing the slender waist and deep navel associated with virginity while hiding the legs and genital region.”

Agreeing with Dwyer, Wilkinson-Weber, when talking about the saris sensual aspects asserted:

“Hindi films have taken full advantage of these possibilities and has even invented some of its own.”

Within Hindi films, often the camera focuses on these erotic zones on the actress wearing the saree.

In particular, in order to display a more erotic and sensual effect, the wet sari scene is used within the films.

The wet saree scene is when actresses are seen in the rain when wearing a saree. The use of water makes the sari cling to the body more and further accentuates the wearers curves.

Dwyer maintained:

“The erotic body here is fully-clothed but totally sensualised to the point of being orgasmic.”

This wet sari scene can be seen within films such as Mr India(1987), Saagar(1985), Mohra(1994) and Chameli(2004).

In particular, the song “Kaate Nahi Kat Te Din Yeh Raat” within Mr India displays this orgasmic nature of the wet sari Dwyer referred to.

Watch Kaate Nahi Kat Te Din Yeh Raat Here

Dwyer, speaking on the use of the wet sari, asserts:

“The wet sari sequences can provide a particular celebration of the erotic, rather than the pornographic body.”

While these scenes are meant to be erotic, they are simultaneously regarded as suitable family viewing.

Nakedness is viewed as a source of disgrace and shame within Indian culture. The fact the female body is covered by the sari within these scenes makes it a far more tasteful version of eroticism.

The fact the saree is used within the Hindi film industry as a means of tasteful eroticism highlights how the sari is further a “lived garment”. It is a garment that has multiple stories and meanings in different contexts.

The Literacy Significance: A Feminist or Anti-Feminist Garment?

As this article has discussed, the saree is an extremely lauded object that holds a number of significances depending on how and where it is worn.

In the late 20th century, the sari also became the subject of feminist poems. In Zare and Mohammed’s article they assert:

“In recent decades, two poems have used the sari to consider the constrained experiences of women, using a familiar material item to articulate an emotionally charged discourse about social justice.”

The two poems mentioned are Jayaprabha’s Telugu poem ‘Burn the Sari’ (1988) and Jupaka Subadra’s poem ‘Kongu, No Sentry on my Bosom’ (1997). Sabadra’s poem was a response to Telugu’s earlier poem.

‘Burn the Sari’ criticises the sari and expresses how it enforces patriarchal ideals. An excerpt from ‘Burn the Sari’ reads:

“Burn this sari.

When I see this end

Of the sari on my shoulder

I think of chastity, a log

Hung from my neck.

It does not let me stand up straight

It presses my chest with its hands

bows me down,

teaches me shame

and whirls around me

a certain bird-like confusion.”

The poem presents the saree as an item that weighs down women’s freedom. As the poem progresses, the speaker mentions how the saree embodies an “unseen patriarchal hand”.

‘Burn the Sari’ rejects the sari and ultimately presents it as a restricting item that restricts a woman’s role.

On the other hand, Subadra’s “Kondu, No Sentry on my Bossom” presents a different side on the role of the sari for lower-class working women.

An excerpt from ‘Kondu, No Sentry on my Bossom’ reads:

“When my sweat streams for wages,

My Kongu blots sweat on my face as breeze.

When I stack star-like

Grains, tubers, granules in my kongu,

It twinkles on my head like a moon.

When wearied working the fields and crops,

My kongu offers me relief as

A cloth for napping on bare floor”

Another excerpt of the poem reads:

“It’s an inalienable part of my sweat and work

Bed, pleasure and sorrow.”

The poem concludes by directly addressing ‘Burn the Sari’:

“My kongu is at work ceaselessly.

It’s not a sentry on my bosom.

It’s not a burden on my heart.

How do I blame it in public?

How could I survive setting it aflame?”

Subadra almost refers to the sari as a second skin for daily labourers.

The sari, rather than representing a restricting chain is presented as a key aid during the “relentless demands and physical motions of work”. The sari holds pride of place in all aspects of a woman’s day.

Zare and Mohammed when talking about the two poems assert:

“Jayaprabha’s Burn the Sari brings welcome attention to the saris operation as a kind of chastity belt and launches an important dialogue about how clothing traditions may suppress freedom of expression and constrain women’s behaviour.”

Further adding:

“Subadra’s response provides readers with a perspective from a low caste daily labourer and forces us to recognize both the vulnerability and resilience of bodies subjected to constant toil and impoverishment.”

The poems offer two different perspectives on the sari’s status. While both poems offer differing views, one coherent theme that can be drawn is the power of the sari.

The sari is far more than just a piece of cloth you wrap around yourself, it has deep cultural meanings woven into it.

It can be a symbol of constraint for some, while a symbol of daily hardships for others. It truly is a “lived garment” with multiple stories.

The sari is much more than an item of clothing, but rather a garment with a deep significance. We have discussed the multiple meanings of the sari in depth.

It is a charged symbol that not only embodies Indian tradition and culture, but also eroticism, chastity, modernity and femininity.

The sari truly is a “lived garment” that grows and progresses through all stages of life with an Indian woman. A true ‘Indian phenomenon’.

So, next time you wear a sari or see someone wearing a sari remember there is more to it than meets the eye.

It is a magnificent garment that tells multiple stories and has a deep significance weaved into it.