This new cinema was often a caricature

Currently, Pakistani cinema presents a profound and unsettling paradox.

In a nation of 240 million people, a land teeming with raw, untold stories of resilience, struggle, and joy, its cinematic voice seems to have grown faint, almost to a whisper.

What is offered up today under the banner of a national film industry often feels less like a cohesive art form and more like a disjointed patchwork of familiar celebrity faces, recycled humour, and a glamour so heavily borrowed it feels alien.

The problem is not that Pakistanis have fallen out of love with the cinema; it is that the cinema has given them precious little worth loving anymore.

Whilst other national cinemas serve as a mirror to society, provoking debate and even inspiring reform,

Pakistan’s mainstream offerings are too frequently a glossy, two-hour diversion that evaporates from the mind the moment the house lights come up.

In a land full of stories, the screen has largely stopped telling them.

A Bygone Era

Pakistan’s cinematic journey began with a fragile but palpable sincerity in the years after independence.

The industry’s inception, marked by films like Teri Yaad (1948), was modest in its resources but monumental in its earnestness.

This was a cinema born of a new nation’s desire to see itself on screen, to forge an identity from the ashes of Partition.

The golden period of the 1960s and 1970s saw this ambition blossom.

The arrival of colour with Sangam (1964) introduced a new vibrancy, yet spectacle never overshadowed substance.

Films like Armaan (1966), a poignant story of love and amnesia, or Naila (1965) and Salgirah (1969), were more than just popular entertainment; they were cultural touchstones that explored complex themes of love, duty, and sacrifice with a delicate touch.

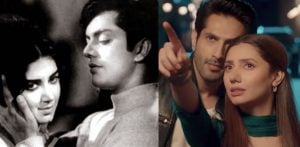

This era was defined by stars like Waheed Murad, Mohammad Ali, Nadeem, Zeba, and Shabnam. They possessed a kind of innocent sincerity that made their performances credible and deeply relatable.

Behind the camera, a formidable intellectual collective was at work. Writers such as Masroor Anwar and directors like Pervez Malik and Nazrul Islam understood that cinema’s primary duty was to tell a compelling story.

The music of this period was its soul, with songs that were philosophies set to melody, not mere commercial fillers.

Poets like Qateel Shifai and Ahmad Rahi wrote literature, not jingles, crafting lyrics that gave ordinary people the language to express their deepest emotions.

Classics like ‘Rafta Rafta Woh Meri Hasti Ka Samaan Ho Gaye’ became timeless anthems because they were born from artistic integrity, a quality that now feels in desperately short supply.

When Did Things Start to Decline?

Like all golden ages, this one eventually began to tarnish.

The decline of Pakistani cinema, which began in the late 1970s and accelerated through the 1980s, was not a single event but a slow, creeping decay.

The socio-political landscape of the country shifted dramatically, and a stricter censorship regime began to stifle creative expression, making it difficult to produce the nuanced social dramas that had once been the industry’s hallmark.

Into this creative vacuum thundered the Punjabi cinema wave, a genre that, whilst commercially potent for a time, ultimately did irreparable damage.

The delicate stories in Urdu cinema were ripped apart and replaced by loud, exaggerated, and often brutish tales of revenge, dominated by the iconography of the gandasa (a bladed weapon).

This new cinema was often a caricature, divorced from the rich cultural realities of the Punjab it claimed to represent.

The rise of the gandasa film alienated a vast segment of the family audience that had been the bedrock of cinema’s success. This internal decay was mirrored by an external one.

By the late 1990s, cinema halls were closing down at an alarming rate. A country that once boasted over 700 cinemas saw that number plummet to less than 100 by the early 2000s.

In a sadly fitting metaphor, many of these venues were converted into marriage halls, a physical manifestation of communal storytelling being abandoned in favour of private, gilded functions.

Revival Attempts

Throughout the decline, there were glimmers of hope that kept the flame from extinguishing entirely.

The era of Babra Sharif, an actress of immense charm and versatility, provided a lifeline.

Her ability to shift from glamorous heroine to emotionally intense character in films like Mera Naam Hai Mohabbat (1975) and Shabana (1976) showcased the enduring power of a great performance.

Later, Javed Sheikh’s successful transition from television to the big screen offered another anchor during the turbulent 1980s and 90s.

The most significant promise of a true “revival,” however, emerged in the 2000s with the work of director Shoaib Mansoor.

His films, Khuda Kay Liye (2007) and Bol (2011), were cinematic events. They were bold, relevant, and deeply Pakistani, proving that audiences were starved for serious films that tackled complex social issues.

Yet, this revival proved to be a false dawn.

These courageous films were exceptions.

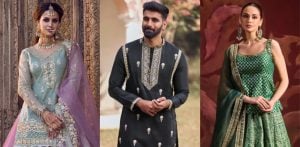

Instead of moving towards more meaningful content, the industry opted for a high-gloss, high-budget aesthetic that prioritised style over substance.

Today’s mainstream films often resemble overlong wedding photoshoots or extended brand commercials, complete with a dash of borrowed Bollywood choreography.

They are afflicted by what can only be described as a crisis of imagination, evident even in their titles: Karachi Se Lahore, Punjab Nahi Jaungi.

It is a geographical obsession that suggests a creative bankruptcy, a stark contrast to the evocative, emotional titles of the past like Armaan, Aina, and Bandish.

The current output is often a cinema of Botox without a story, a hollow glamour that fails to connect because it has no soul.

Identity Crisis

One of the biggest reasons why Pakistani cinema is currently struggling is down to the fact that many Pakistanis no longer see their own lives, struggles, or aspirations reflected on screen.

The simple, heartfelt stories of the common person have been supplanted by the insulated, unrelatable world of an elite class.

This disconnect is exacerbated by a crippling lack of new talent.

The industry has become a closed loop, with the same handful of actors, Humayun Saeed, Mahira Khan, Mehwish Hayat, Fahad Mustafa, circulating between television dramas and film projects.

This monotonous casting makes the cinematic landscape feel predictable and stagnant.

Unlike healthy film industries that constantly introduce new faces and nurture separate stars for film and television, Pakistan’s acting pool has become an exclusive club, blurring the lines between the two mediums and ultimately devaluing the cinematic experience.

Beneath this surface-level problem lies a deeper, systemic issue: a near-total absence of infrastructure.

Film direction is a craft, yet there is a dearth of credible academies to train writers, directors, editors, and producers. Passion without craft is hollow.

This leads to formulaic films and a fear of experimentation.

Whilst courageous filmmakers occasionally produce gems like John, a film about the struggles of a Christian boy facing discrimination, these works are rarely given the promotional support they deserve.

Instead, weak films are over-promoted with billboards and talk show appearances – all hype, no heart.

Globally, cinema is a powerful tool for social commentary.

A film like Korea’s Silenced (2011) was so impactful that it forced legal reform.

Even mainstream Indian cinema often explores challenging themes in films like Article 15 or 12th Fail.

Pakistani cinema, by contrast, largely avoids the nation’s most pressing issues, favouring forgettable comedies over films that could truly hold a mirror up to society.

Ultimately, for Pakistani cinema to be reborn, it must stop looking outwards for validation and look inwards for its stories.

The country does not lack narratives; it lacks the courage and the vision to tell them on screen.

The soul of its golden age was built on the words of poets and the conviction of storytellers, not on foreign locations and celebrity cameos.

Pakistani cinema today stands at a crossroads, haunted by the ghosts of its glorious past and hobbled by the insecurities of its present.

The potential for a true revival exists, but it will require more than just bigger budgets and slicker production.

It will require a return to authenticity and a willingness to reflect the complex, vibrant, and often difficult reality of Pakistani life.

Until then, the screen will remain a flickering, polished surface, reflecting little of substance, playing out its borrowed dreams in a mostly empty hall.