"It’s really important that we see ourselves reflected."

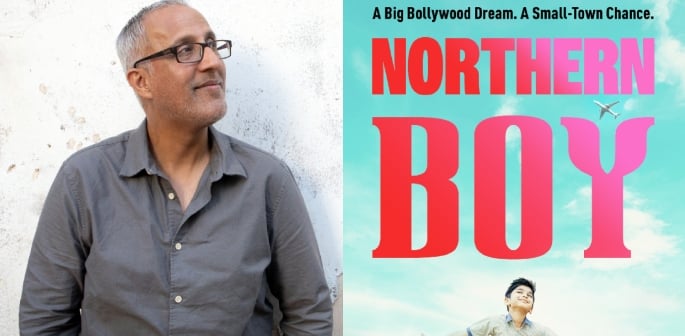

In the realm of novels and writing, Iqbal Hussain beams with promise and his potential.

His debut novel, Northern Boy was published on June 6, 2024 and explores several issues from a Desi perspective.

Narrating the story of the main protagonist, Rafi Aziz, the book encapsulates emotion and triumph through a curious and creative lens.

Iqbal has arrived as a novelist with a bang and the book is certainly a rousing read.

Praising Northern Boy, the author Jennie Godfrey said: “I laughed and cried and nodded my head in recognition.

“If it doesn’t get a movie deal, there is no justice.”

In our exclusive chat, Iqbal Hussain delved into what inspired him to write Northern Boy and his illustrious career so far.

Can you tell us a bit about Northern Boy? What is the story?

Northern Boy is the story of Rafi Aziz, a precocious 10-year-old growing up in 1981 in the north of England.

Northern Boy is the story of Rafi Aziz, a precocious 10-year-old growing up in 1981 in the north of England.

To quote a line from the book, Rafi is a “butterfly among the bricks” – he’s flamboyant, gregarious and fey – not an easy thing to be in a community that encourages conformity and frowns upon difference.

We follow Rafi’s journey over the years, to see how he negotiates the strictures being placed upon him.

We also take in the story of his mother, who is as much trapped by circumstances as her son is.

She was married at the age of 14 to a man more than double her age, so while Rafi tries to act older than his years, his mother tries to recapture her lost youth.

Throughout the book, we see how their struggles interact with each other and what that says to us about the expectations of family versus the desire to follow your dreams.

What made you want to tell Rafi’s story?

Even though things are getting better, there are still few books that feature working-class characters, even fewer with Northern settings and fewer still from South Asian backgrounds.

Even though things are getting better, there are still few books that feature working-class characters, even fewer with Northern settings and fewer still from South Asian backgrounds.

We’ve all read great books that have been set in wealthy households in India or Pakistan, with servants, drivers and a never-ending round of parties, but that isn’t my reality.

I wanted to write about a “normal” family from a Pakistani background, to describe a typical lounge in a modest terraced home, to write about the neighbourhood of old Edwardian houses that have had years of neglect, to talk about tight-knit communities where, seemingly, everyone knows what you’re up to.

I also wanted to write a book about an outsider, which Rafi certainly is.

He’s camp and extravagant as a child, which has always been fine with his family until he’s deemed to be too old to indulge in such “nonsense” – and then we get the oft-trotted out: “What will the neighbours say?”

That forms the background to many of our upbringings in Asian households.

Do you think homosexuality and flamboyance are still yet to be accepted in the Desi community? If so, what steps need to be taken?

Surprisingly, for a community that celebrates excess – just think of your average Bollywood movie or an Asian wedding – we can be conservative when it comes to any perceived differences within the social structure of a community.

Surprisingly, for a community that celebrates excess – just think of your average Bollywood movie or an Asian wedding – we can be conservative when it comes to any perceived differences within the social structure of a community.

Parents still hold on to values they or their parents came over with from the Indian Sub-continent.

Still waters run deep and it will take several generations yet before there’s an ease with issues such as homosexuality and flamboyance.

Even in the otherwise liberal Bollywood film world, there are very few – if any – out actors or actresses.

There are a handful of films that deal with sexuality or gender. Often, these topics are seen as elements of a Western lifestyle, rather than facets that are inherent in a person.

I honestly don’t know how we change these attitudes.

I would like to think that it’ll be the young generation that will lead the way, but even that isn’t a given, as often we inherit the thinking and beliefs of our parents and it can be hard to challenge those.

Does Rafi’s story play into the typical masculine stereotypes of Desi families? What can be done to overcome these expectations?

Rafi has to challenge himself constantly throughout the book to enable him to be authentic to himself.

Rafi has to challenge himself constantly throughout the book to enable him to be authentic to himself.

As I said earlier, this wasn’t an issue for him when he was a child, when it would be laughed off or viewed fondly by adults observing him.

But the older he gets, those same adults want him to tone down his behaviour. As Rafi observes in the book: “But this is me. I don’t know how else to be.”

There is comfort in expectation, in doing things the same way, in each generation enacting the same roles as the previous.

But it’s a false comfort as no one is being true to themselves – so, not Rafi.

If he feels he can’t wear the colourful outfits he wants to wear, and not his mother, if she chooses not to see what she doesn’t want to see.

A large part of changing this will need to be for the older generation to be more open to things that cause them misgivings, and not to view things as binary – right or wrong.

This isn’t an easy hurdle to get over, but I’m hopeful with time things will change.

Parents should want their children to be happy in their own skin, not to force a version of their own happiness on them because of fears of what the wider community might say.

Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to pursue writing as a career?

I’ve always written, from as far back as I can remember. Dad used to buy me typewriters at the auctions he loved, and I was always tap-tap-tapping away on faux Enid Blyton stories.

I’ve always written, from as far back as I can remember. Dad used to buy me typewriters at the auctions he loved, and I was always tap-tap-tapping away on faux Enid Blyton stories.

I wrote for the student newspaper, then worked in journalism and publishing for some years. I’ve now turned my hand to writing fiction, which is a very different discipline than writing for magazines and newspapers.

I’ve written several short stories, some of which can be found online, including my favourite story, The Reluctant Bride about a ghostly midnight rickshaw ride through rural Pakistan.

Northern Boy is my first novel. It’s liberating to be given free rein to write about whatever you want without being constrained by the format of a news article.

Having said that, it still needs research – for Northern Boy, which is largely set in 1981, I had to keep checking to make sure that certain songs, TV programmes and foods were around back then.

It was with much regret that I realised Madhur Jaffrey’s cookery shows weren’t on TV until 1982.

I think it’s really important that we see ourselves reflected in the books we read. It’s definitely getting better.

There are many more Asian writers now than when I was a child, including Sairish Hussain, Awais Khan, Neema Shah and Hema Sukumar, so we’re definitely heading in the right direction.

What advice would you give to young Desi people who want to become novelists?

I would say just to go for it! First thing, read widely. You can’t write well until you’ve read enough other books to see how published authors have done it.

I would say just to go for it! First thing, read widely. You can’t write well until you’ve read enough other books to see how published authors have done it.

This is especially true if you want to write a book in a genre, such as crime or horror.

If you want to write children’s books, read current children’s books rather than relying on your memory of what the books of your childhood were like.

Times move, fashions change, and you need to be on it. What books do you enjoy reading? Spend some time analysing the writing styles of writers you admire.

Then write about whatever you want to write about – not just about what you know which I know is one of those oft-quoted pieces of advice.

If you want to write a story set on an international space station, do it.

As long as it’s researched well and is believable, you’ve as much right to write about that as anyone else.

You don’t have to write about your own life or experiences. That’s the whole point of literature – we can use our imaginations (and Google!) to tell whatever tale we want to tell.

Are there any themes and ideas that particularly fascinate you as a writer?

I’m often drawn to themes of childhood, nostalgia, and the North. That doesn’t mean to say I write about my own experiences necessarily, but they’ve certainly informed me.

I’m often drawn to themes of childhood, nostalgia, and the North. That doesn’t mean to say I write about my own experiences necessarily, but they’ve certainly informed me.

I find the passage of time fascinating, so I often write about that in some form.

I like family dynamics, so I write about those too. I also love horror and the supernatural, so that’s always in the back of my mind.

I’d like to write a scary Young Adult novel with a djinn at the centre of it – again, something I’ve heard about growing up, just percolating away until the right idea comes out and I want to get it down on paper.

Northern Boy is written with a lot of humour, as that’s something that comes naturally to me.

But it’s balanced with a similar amount of pathos. You definitely need that balance.

It also harks back to something my mum used to say to us as kids, especially when we were being super-boisterous: “As much as you’re laughing now, you’ll cry later.”

As much as I hated hearing that at the time, it’s clearly stuck with me at some level.

How has a published novel impacted you as a writer and as a person?

It’s still astonishing to me when I walk into a bookshop and see my book on the shelf.

It’s still astonishing to me when I walk into a bookshop and see my book on the shelf.

The child me would never have believed I’d one day see my book in a proper bookshop, and alongside two other writers who share my surname and heritage – Nadiya and Sairish Hussain.

Back then, there were so few writers from an Asian background. I can only remember Farrukh Dhondy, Hanif Kureishi and Jamila Gavin.

The route to publication wasn’t straightforward. My agent, Robert Caskie, submitted the book widely but we had no takers.

This seems to be a common experience with other writer friends, but when it happens to you it’s still of no comfort.

I was all set to shelve the book, when, on the off-chance, I spotted a competition being run by the publisher Unbound.

They were looking for two books to publish from debut writers of colour for their new imprint, Unbound Firsts.

I was shocked, thrilled and disbelieving when I won, alongside fellow winner Zahra Barri, whose book Daughters of the Nile is a great read.

The whole team have done an amazing job in bringing my vision to life. I’ve had lovely book reviews online. I’ve done library visits.

I’ve even spoken about it at WOMAD and had Sewing Bee’s Patrick Grant buy a copy! I feel humbled and honoured and incredibly lucky.

And that sense of joy and delight doesn’t ever go away.

Can you tell us about your future work?

I’m currently working on my debut children’s novel. I can’t say too much about it, as even though I’ve managed to get a two-book deal with a major publisher, we haven’t announced the news officially yet.

I’m currently working on my debut children’s novel. I can’t say too much about it, as even though I’ve managed to get a two-book deal with a major publisher, we haven’t announced the news officially yet.

The book is set in a similar world to Northern Boy – another working-class, Pakistani household up North.

But this time there’s an element of fantasy to proceedings. We talked about themes earlier, and this book again has family, including a crabby granny, and plenty of nostalgia and the passing of time.

As with Northern Boy, I’ve laughed and cried while writing the book, and I hope readers will connect with me in the same way.

It should be out in Spring 2026.

What do you hope readers will take away from Northern Boy?

To be true to yourself, no matter how hard or impossible that might seem. And for others to allow people to do this.

To be true to yourself, no matter how hard or impossible that might seem. And for others to allow people to do this.

There is a line in the book, a famous Shakespearean quote: “To thine own self be true.”

I can’t think of a more fitting message to take away from the book.

And, also I hope that readers reflect on how much has changed since the book starts in 1981 to when it finishes, just before the pandemic starts.

We’ve come a long way, and we should allow ourselves a pat on the back for that.

There is still much more to be done, on many fronts, but we should recognise the victories along the way.

Iqbal Hussain is a gifted writer with an undeniable flair for weaving entertaining tales around somewhat sensitive material.

His knack for great storytelling has introduced his talent with a bang and the result is there for all to see.

Northern Boy is a gripping story of hope, challenges, and determination.

If you haven’t read Northern Boy yet, you can order your copy here.