Homemade masala was very common in the 70s and 80s.

British Asian food in households continues to change throughout time.

Traditional food usually made in British Asian households is gradually getting less popular, as the newer generations of Asians born in Britain switch their tastes to try different foods.

Each palate is tried, tested and adapted in a manner that a household enjoys. Some spices are added and even the elders of the family do enjoy the spicy baked beans.

As newer cuisines from foreign countries have made an entry into most British Asian homes, the traditional curry, daal, roti and rice combination have gradually simmered down.

From Friday fish and chips to a Sunday roast dinner to frequent pasta, pizza and kebabs, all of these have contributed to the eating habits in British Asian food in households.

There are many reasons as to why food has evolved so much in British Asian homes, and one could say that the change is inevitable when living and being raised in a western country.

Where did this evolution of British Asian food begin, and what were the reasons? We explore to find out.

Migrants and Food

When Asian men arrived from India, Africa, Pakistan and Bangladesh from the early 1930s without their wives or family, they had to adapt to eat the food that was available.

Plenty of Asian men who were pure vegetarian or did not eat pork or beef had to adapt their pallet but found it hard to integrate with the British food culture.

Men had to learn how to use whatever was available to them and make food that resembled Desi cooking, e.g. baked beans curry and Indian omelettes.

Many Desi men relied on one or two who could cook in a household, where most lived together as they worked shifts.

Some men even began to make chapattis and learned to cook more complicated dishes from the cravings they had for food to taste like back home.

However, once their wives arrived in the UK sometime after, the overall style of British Asian food at home changed.

Spices and exotic vegetables were not readily available in supermarkets like they are today.

Smuggling things back from the homeland or a special trip to far places selling spices or ingredients were the only way Asian families were able to buy what they needed.

Homemade masala was very common in the 1970s and 1980s.

It was a long process of roasting a variety of whole spices such as cardamom, black pepper, cinnamon, star anise, bay leaves, red chilli, coriander, cumin and cloves.

Once roasted and cooled, the whole spices would be blended in a coffee grinder, which was the easiest and quickest method at the time. Prior to this, a pestle and mortar were used in some households.

The taste was great, but the smell was pungent.

Meat was considered to be a luxury in comparison to today. The availability of halal meat was extremely limited.

So, cooking Desi chicken or lamb became a treat for families.

Besides, not everyone knew how to make meat because mostly, Asian people were used to eating vegetarian options like daal and sabzi (vegetables). But eventually, this changed.

Due to demand, the emergence of Asian food stores selling ingredients, vegetables, fruit, oils, ghee, rice, chappati flour, meat and spices became the norm and made it very easy for Asian households to make Desi food in an economic way.

As much as families loved their Asian food, other cuisines slowly seeped their way into their daily meals.

Generational Change

It is still a common occurrence for the elders in the house to dislike English and other foreign cuisines.

However, for British Asian’s, especially the first generation to be born and bred in England, would see their English meal as a special treat growing up.

The preference differed for every Asian family.

Some would treat themselves to fish and chips in the weekend, whilst some Asian families (still adverse to eating out) would make homemade chips and eggs.

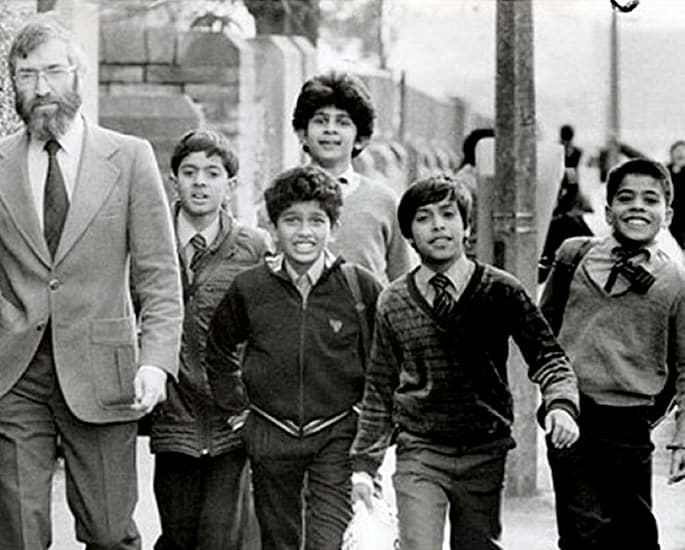

The generational change began with the first group of British Asians who were introduced to English and western food at school.

This was different from the food that they were used to eating at home, which was usually roti, daal, sabzi, rice and curried meat.

Other changes that impacted British Asian food was the evolution of women going to work.

The Evolution of Asian Women

In the 1960s, it was typical for the women in the house to cook Desi food at home whilst their fathers or husbands went out to work.

It wasn’t considered unfair or discriminatory, it was simply the norm.

In the 1980s, a lot of Asian women decided to work instead of being a housewife. One of the key reasons was for an additional household income.

Due to the increase in Asian women working, studying and becoming professionals, most everyday meals, which would usually be Asian food, got slowly replaced by western food.

This was due to the fact that making Asian food is usually very time consuming, and often families will opt out and make western food which is quicker, e.g. pasta, pizza and chips.

The stigma of Asian men making the dinner for the family is less effective now that both the man and woman of the house are able to work.

Some Asian households that include an elder generation sometimes still make Asian food on a daily basis because of the grandma or grandad’s distaste for western food.

Eating Out and the Introduction to Foreign Foods

By the late 1970’s and 80’s British Asians began to eat out more.

The Italian revolution of pasta and pizzas had started, which eventually overtook Indian food as the most popular take-out.

Chinese food was also becoming popular, along with other cuisines like Mexican, which was similar in spices to Desi food.

Curry houses were at its’ peak in the 1980’s and 90’s also, with British people favouring it above all other take-outs.

The first curry house, the Hindoostanee Curry House in London, opened up in Britain in 1809.

With British people unfamiliar with our cuisine at the time, the restaurant eventually shut down.

However, the idea of a pint, curry and chips became the most popular in Britain, with British Asian people jumping on the trend also.

As the income in British Asian houses increased there was more leniency to go out for dinner.

Curry houses and Chinese restaurants were amongst the particular type of restaurants that were considered casual and affordable.

British Asians did not have to see eating out as a special occasion anymore.

As British Asian’s integration with other ethnicities and cultures in the UK increased, so did their food pallet.

Every high street features multiple chain restaurants that specialise in food from around the world.

Curry houses are doing less successful now than ever before due to the increase of interest in Japanese, Mexican and Italian cuisines, and it is reflected within British Asian households also.

With trendy diets, celebrity chefs and readily available foreign food, British Asian’s have opened their dining world further than the Desi food they might’ve grown up with.

How the British Adapted Asian Food

The British culture’s love of curry goes back to colonial rule days. The word curry itself is described as not being Indian.

Historically, the British are known for taking another culture’s traditions and adapting it to their own preference.

It has been claimed that the Chicken Tikka Masala is actually from Scotland, and a British chef who had travelled from India invented it in 1971.

With curry becoming popular in British households, Chicken Tikka Masala became the British national dish in the UK. surpassing fish and chips.

The British had invented the Vindaloo, which is a very common curry in England after they left India. It is known for its spice and heat. It is claimed that they had a similar dish in Portugal but that was made with red wine.

Indian restaurants in the 1970s and 1980s in Britain although called ‘Indian’ were mostly run by Bangladeshis. A lot of the dishes made were for the British palate some toned with sugar or cream to reduce the heat of the spices.

Many dishes on Indian restaurant menus were never really heard of in Asian households.

The Balti is believed to have been invented in Birmingham in the 1960s by the Pakistani community, first appearing on a restaurant menu in 1977.

These cultural influences have had some influence on how British Asian’s eat their food within their households. But the majority still cook their food the traditional way which has been passed down the generations.

The biggest difference is that British Asian households are not regularly cooking Desi food as they did in the past. So, a lot of the cooking skills are gradually diminishing.

Reliance on recipes available online has definitely provided an insight to anyone wishing to cook Desi food.

According to the most recent statistical Census, 6.8% of the population in England and Wales are Pakistani, Indian, Bangladeshi, or belong to another south Asian country.

This statistic plays a part in how western lifestyles around British Asian’s have influenced their household decisions.

Supermarket Gains

Some revolutionary changes occurred when Britain started to provide substitutes for home-made curries.

Companies such as Patak’s, Sharwoods and Geeta’s provided the nation with an opportunity to make curry at home with minimal effort.

L.G. Pathak was born in 1925 in Gujarat, he and his wife had the idea of selling curry from home as they missed the taste of home when they moved to Kentish Town in 1956.

With the surge of immigration in the 1950’s and 1960’s, the famous East End Food’s company began distributing raw materials from Africa and India to meet the demand of Asian migrants.

Other brands in the UK which started to create and produce herbs, oils and spices for Desi cooking include Natco, Raja, KTC, TRS and Indus.

These lightbulb ideas have become multi-million-pound companies and still supply the majority of raw South Asian materials directly to supermarkets today.

Supermarkets’ have recognised their competition and have jumped on the band-wagon of supplying raw materials in a convenient way.

Frozen garlic, ginger, coriander, onion, parathas, roti, green chillis and many more are now readily available in supermarkets to use.

They can never beat a fresh roti or paratha but are popular due to the time saving for busy lives since more and more Brit Asians are living in cities and towns where they work, often alone.

British Asian food will continue to evolve and adapt due to multiple factors; whether it be a decline in home-cooking or an increase in eating out.

Regardless of the factor, Desi food will continue to hold a place in most British Asian homes as it is the staple and reminder of being belonging to a South Asian heritage.