"They robbed me of my children's childhood"

In the late-1970s, the case of Anwar Ditta was the highest-profile immigration battle of its time.

Anwar Ditta took on the home office after unfair immigration laws kept her away from her three young children for six years.

As the post-War years progressed, following the boom in coloured immigrants to the UK, immigration laws became stricter and stricter.

Alongside these laws, the Home Office became stricter in monitoring and accepting immigration cases.

By the 1970s, many immigration officers often asked complex questions to deliberately trick migrants.

The British immigration policy is widely known to be built upon deep-seated imperial racist prejudices and attitudes.

These stricter laws were viewed by many as the ‘nationalisation of racism’ in Britain.

Many cases arose of South Asian and Black immigrants being unfairly treated by the Immigration officials.

DESIblitz looks at the story of one mother’s traumatic experience with the British immigration policy.

Who is Anwar Ditta?

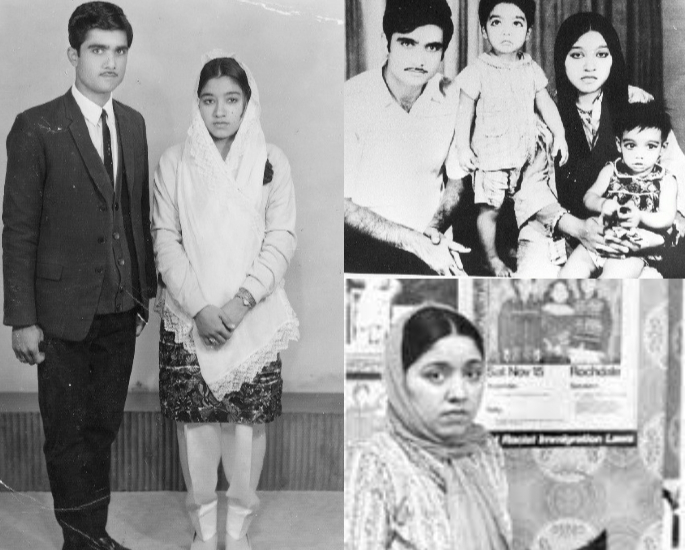

Anwar Ditta was born in Birmingham, England, in 1953 and brought up in Rochdale.

Like many South Asian men and women in the post-War years, her parents migrated to Britain from Pakistan.

In 1962, her parents separated and her father was given custody of her and her sister. Both children were then sent to Pakistan to live with relatives.

In 1968, Anwar married Shuja Ud Din and they had three children; Kamran, Imran and Saima. In 1974, her husband decided to come to England and in 1975, Anwar joined him.

They decided to leave their children in Pakistan with relatives while they secured a house and a job in Rochdale.

On their arrival in Britain, they thought their Islamic marriage would not be recognised under British law, so they remarried.

While in Britain Anwar gave birth to her fourth child, a daughter, Samera.

While Anwar was automatically allowed into Britain, due to her British passport, her Pakistani born children had to apply for entry.

A booklet detailing Anwar’s story by the Manchester Central Library maintained:

“Anwar’s return to England came at a time when the government was using harsh methods to restrict the rights of Black and Asian immigrants.

“Open hostility towards immigrants was prevalent. The Nationalist Party blamed them for social grievances and urged the Government to end immigration altogether.”

Immigration laws and monitoring became stricter during the 1960s and 1970s.

In particular, the Commonwealth Immigration Act of 1968 and the Immigration Act of 1971 greatly restricted migrants coming to Britain.

In 1976, they applied for their children to come over to Britain. Both Anwar and Shuja were interviewed by immigration authorities in February 1978.

In October 2020, on the Tell a Friend podcast, Anwar was interviewed by Bryan Knight. When describing her story, she recalled:

“I applied for my children and that’s where my nightmare began with the immigration authorities.”

In May 1979, the British High Commission in Islamabad refused to give Anwar’s children entry into Britain, on the grounds that they were:

“Not satisfied that Kamran, Imran and Saima were related to Anwar Sultana Ditta and Shuja Ud Din as claimed.”

Further expressing:

“That no clear evidence of Anwar Sultana Ditta ever having been in Pakistan had been produced.

“It appeared that there might be two Anwar Dittas, i.e. one who married Shuja-u-din in Pakistan in 1968 and the other who Shuja-u-din married in the United Kingdom in 1975.”

Anwar was heartbroken over the Home Office’s incorrect speculation, she asserted:

“I was devastated. There’s no words to describe somebody turning around, saying something that’s yours, is not yours.

“You carry your children for nine months, you give birth to your children and they’re just turning around and saying that they’re not yours. It was very painful.”

Anwar, flooded with sadness and anger, had to find a way to be reunited with her children.

The Anwar Ditta Defence Campaign

Following the Home Office’s decision, Anwar and her husband appealed the decision in June 1979. Anwar also provided a great deal of proof that the children were hers.

She sent birth certificates, photographs of her marriage and of her children.

As well as hospital confirmation that Samera, born in Rochdale, was her fourth pregnancy.

Despite all this evidence collected, the Home Office still did not budge on their decision. They in fact believed the children belonged to Anwar’s sister-in-law.

Anwar, distressed over the Home Office’s unfair claims, attended a public anti-deportation meeting at Longsight Library in South Manchester.

After this meeting, Anwar believed the only way she would be reunited with her children was if she campaigned.

In November 1979 the Anwar Ditta Defence Committee (ADDC) was formed.

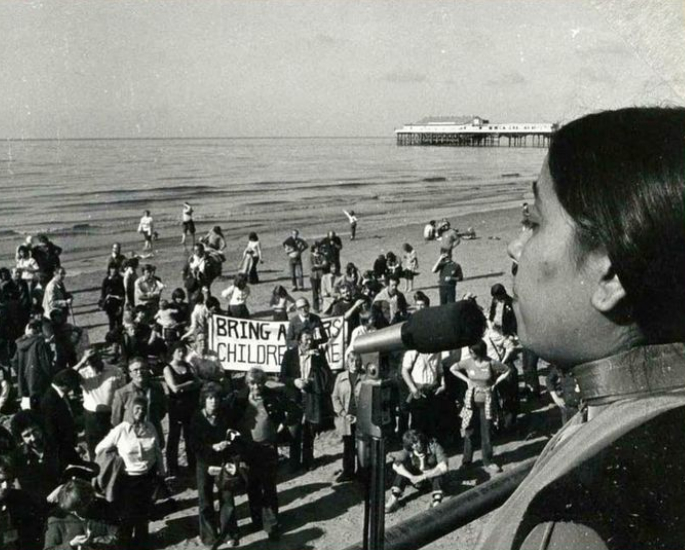

The appeal was heard on 28th April and 16th May 1980. During these weeks, the ADDC carried out many rallies and demonstrations all over England.

Anwar delivered speeches at many rallies. Within the Tell a Friend podcast, Anwar recalled her determination:

“There’s no place where I haven’t spoken. I spoke in a lot of meetings; you name it I have been there.

“I used to go every weekend down into the town centre with a bucket and petitioning, going door to door begging people ‘please sign my petition for my children, to help me bring them home.’”

Hundreds of people attended these rallies in support of Anwar, which included celebrities and politicians.

The ADDC was also heavily supported by many anti-racist campaign groups.

This included: the Asian Youth Movement, Women Against Imperialism, Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism!, Rochdale Against Racism and the Anti-Racism Committee of Manchester City Labour Party.

As time went on the campaign grew stronger and stronger. Due to the huge public support, the Anwar Ditta case reached national headlines frequently in the 1980s.

In the podcast, Anwar reiterated the power of the public’s support:

“The people were behind me, people believed me. The home office didn’t believe me, but the people did.”

During this time Anwar also declared that she would be willing to do anything to be reunited with her children. In an ADDC pamphlet she pleaded:

“I am willing to give a medical test. I am willing to give a skin test. I am willing to go onto a lie detector to prove that they are my children.

“I’m not telling them any lies, why should I tell them lies? Why should I claim other people’s children?”

However, the Home Office did not acknowledge this. One only imagine the distress of a mother who has to go through being away from her children and having to prove they are yours.

Within another campaign pamphlet, Anwar expressed her feelings towards the Home Office’s refusal to budge:

“When a person commits a crime, for example, murder, they only need one or two witnesses to convict him.

“I’ve got more than ten or twenty witnesses who can prove they are my children, but the Home Office doesn’t bother to ask them.”

Unfortunately, on 30th July 1980, Anwar’s hopes were shattered when the court rejected her appeal, declaring that:

“The couple had not established that they were the parents of the children.”

This was an unjust claim, considering how much evidence Anwar and her husband had given to the Home Office.

Following the verdict on the 30th July, the Home Office officially declared the case to be closed on 30th September 1980. Awar, quoted in the Manchester Central Library Booklet, maintained:

“When it went for the judiciary review, they just threw the case out. They didn’t even review the case.

“You know the legal system was so against my name and my case. They just threw everything out… I had no choice but to campaign.”

Anwar did not lose hope and continued to campaign despite the case being declared closed.

Campaigners also continued to support her case. Anwar declared in the podcast:

“The more the home office was determined to say no, the stronger I got to fight.”

In December 1980, the ADDC, with the help of Labour MP, Joel Barnett, collected further evidence to be submitted to the Home Office.

The evidence included a medical examination of Anwar and further proof of the fingerprints on her Pakistani identity card.

Once again, the Home Office declared that this evidence was not enough to prove the children were Anwar’s.

Conservative politician, Timothy Raison wrote a letter to Joel Barnett. The letter explained how the evidence given in December 1980 was “fresh new material”, but he:

“Was not convinced that it was sufficient to justify overturning the decision confirmed by the appellate authorities.”

The years of hope and campaigning for justice in fact paid off when Granada Television’s World in Action wanted to produce a documentary.

A press statement from the ADDC maintained that this documentary was their:

“Final effort to prove beyond all doubt that they are related as a parent to child.”

In early 1981, Granada TV sent an investigative team to Pakistan. They also paid for blood tests from Anwar, her husband and her children in Pakistan.

The documentary was released in March 1981 and proved that the children were Anwar and Shuja’s.

After the documentary was released, Raison released a statement allowing the children to be reunited with their parents:

“I now believe that there is the substantial new evidence which I invited you [Joel Barnett] to submit to justify reversing the original decision.

“The entry clearance officer will be instructed to issue entry clearances to Kamran, Umran, and Saima to join Anwar Ditta and Shuja Ud Din.”

On 14th April 1981, Anwar’s determination and hope finally paid off. She was finally reunited with her 3 children.

Anwar, within the podcast, expressed:

“If it wasn’t for World in Action and public support, I don’t think my children would be here.”

An article by Our Migrant Story maintained:

“The Anwar Ditta Defence Campaign is an example of the self-organisation and activism that communities and their supporters participated in to challenge racism in Britain.”

Anwar’s motivation and strength, along with massive public support, granted her an important victory against unjust laws and tactics.

The Effects of the Case

When retrospectively looking at campaigns, like Anwar’s, the focus is mainly paid to the positive outcome of the campaign. While Ditta was eventually reunited with her children the process was not an easy one.

The Home Office’s refusal to believe Anwar caused a great deal of long-lasting trauma and distress.

During the Tell a Friend podcast, Anwar, while crying, asserted:

“I have been through a lot of hell. I wouldn’t wish anything like this to happen to anyone.”

Further explaining that the six years of campaigning and fighting for her children robbed her of an ordinary life:

“You know when we were campaigning, it was so hard.

“I was working day and night, my husband was working. He was coming back from work, he was driving to meetings, I was feeding him while he was driving.

“I was taking my little one, that was born here, with me dropping her off at the next-door neighbour.”

The 6 year-long fight also proved to cause financial strain for her family. Anwar stated:

“We were supporting back home and had the responsibility of the children.

“We had a mortgage to pay here, we were phoning home a lot. Our phone bill came up over £500 pounds once.”

Due to the campaigning taking up a lot of time, Anwar had to frequently take time off work. Eventually, she had to give up her factory job at Marks and Spencer’s.

Within the podcast, she went on to explain that being away from her children took a toll on her mental health. The stress caused by the long battle with the Home Office led to Anwar taking anti-depressants.

Alongside the physical, mental and financial burden, the case also instilled a great deal of fear into Anwar.

Anwar’s campaign took place during a time that saw a heightened backlash against coloured immigrants.

The case is one of the highest-profile immigration cases in Britain. While generally much of the public supported her case, this was not the case for everyone.

Due to the publicity surrounding her campaign, Anwar and her husband also faced a great deal of racism from the public.

Anwar lived in fear both within and outside the home.

Within a 1999 interview with The Guardian, she explained how she still had a sack load of hate mail she received.

She expressed that one letter said:

“You breed like rabbits…all Pakistan will call you mother next.”

She also used to receive letters that contained razor blades, so when she opened them it would cut her.

Within the podcast, she recalled one incident when someone had recognised her at the bus stop and said:

“Why don’t you go back where you came from and I said I come from Birmingham and you know what that person did?

“That person spat on me. These sort of things you cannot forget.”

However, this struggle and trauma the Home Office caused did not just end when she was reunited with her children.

Anwar, when reflecting on the impact of the case, within the Tell a Friend podcast expressed:

“The Home Office has caused a lot of damage.

“The damage that they caused me is a big one, I will never forget that, but the damage that they caused between me and my children, that’s a different thing. Life is hard.”

The separation not just physically tore her family apart, but also emotionally.

Her daughter was still breastfeeding and her sons were only 4 and 5 when she left Pakistan. Therefore, undoubtedly, it would not have been easy to rebuild family unity after being apart for 6 years.

Anwar, speaking exclusively to The Guardian in October 1999, maintained:

“I proved they were my kids to the government, to the immigration officers, to the whole world. But I could never prove to my three kids that I loved them.”

It was difficult for her to reconnect with the children after being apart for so long. The three children also had difficulty adjusting to a new climate, culture, language, and lifestyle in Britain.

It is important for children to have a shared childhood with their siblings. The separation also was difficult for her youngest daughter, Samera, to adjust too. She was suddenly not the only child, but the youngest of four.

The Home Office’s strict immigration laws caused a lot of problems for many innocent people.

Anwar explained how even now that she is a grandmother, she cannot forget the trauma she was put through:

“My grandson is a constant reminder of what I don’t have, of how they robbed me of my children’s childhood.”

The Home Office’s refusal to believe Anwar had many long-term effects on her family life.

Immigration and Racism in Britain

Within Maya Goodfellow’s book Hostile Environment: How Immigrants Became Scapegoats (2019) she affirmed that Ditta’s case:

“Is a mere glimpse of the impact successive pieces of immigration legislation have had on people’s lives.”

Anwar’s case can reveal lengths about how non-white immigrants are treated in Britain. Her story is a heartbreaking one of racism, injustice and the brutality of British immigration policies.

A booklet by the Manchester Central Library detailed the lyrics from a song that was ‘composed in support of Anwar by a well-wisher’:

“Margaret Thatcher is a liar,

Says she believes in family life,

An Englishman must live secure,

With his children and his wife.

But if you’re Asian, then it’s different,

Your family life can go to hell,

Thank Margaret Thatcher that you’re here,

Do you expect your kids as well?”

These lyrics sum up how South Asians are treated by Immigration officials.

Anwar was born in Britain and had a British passport. This goes to show that a British nationality is worth nothing, yet the colour of your skin is worth everything.

Anwar’s story highlights how notions of Britishness are historically constructed and built upon Britain’s colonial history.

It is clear Anwar was not just subjected to this because the Home Office believed she was lying, but because of the colour of her skin.

The Home Office barrister, Peter Scott, quoted in The Guardian in October 1980, acknowledged this unfair treatment:

“The whole system of immigration control is based upon discrimination.

“It is of the essence of the Immigration Act that people will be discriminated against on the ground of race or nationality and it is the function of certain officials to ensure that that discrimination is effective.”

The Home Office has had a long history of not owning up to their behaviour. Anwar expressed:

“Never mind compensation they didn’t even apologise they just said sorry for the delay and allowed the children, that’s it.”

The case shows the great lengths immigration control have gone to control migration to Britain.

They failed to acknowledge credible evidence and caused a great deal of trauma for many individuals.

The publicity of the case raised questions over the fairness of British immigration policies.

While Anwar’s case came into the public eye due to public campaigning, her treatment was not unique.

Many other families in the late-twentieth-century were unfairly treated by British immigration policies.

Historically and even more recently, with the Windrush scandal, the British immigration policy is built on discrimination.

The Windrush scandal does draw parrels to Anwar Ditta’s story. Similarly, immigration laws did a great deal of damage to many lives and tore families apart.

Within the Tell a Friend podcast Anwar pleaded to lawmakers stating:

“Please think before you make the laws. Because it’s been 40 years and my life hasn’t been put together.

“I’m 66 and it still affects me. Please think of the people, human beings, whose lives you’re going to destroy.”

Lessons have not been learnt, as British immigration laws have and still do not think about people’s lives when deciding laws.

Immigrants are just viewed as statistics, rather than actual people with lives and families, and that is what needs to change.