Indian textiles played an important and historical role.

Throughout history, Indian textile printing has influenced social, cultural, and economic life.

India is home to various dye plants, like cotton, which led to the development of multiple textile printing techniques.

Prints include bandha of Orrisa, brocades designed by the Mughals, tie-dye, bandhani and kalamkari from Madhya Pradesh.

Other examples are tribal motifs from Chattisgarh, chungadi of Madurai from Tamil Nadu, zari of Arunachal, and Jamdani of West Bengal.

India is the origin of numerous fabric designs embraced by communities worldwide. It has become one of the largest manufacturers and exporters of block-printed fabrics.

India’s agricultural, seasonal, and ecological textile production processes were a great source of creativity in South Asia’s textile industry.

The richness of textile traditions links people worldwide, for fabrics are a non-verbal language that tells us the cultural history of people, their place in the world, and even their beliefs.

DESIblitz delves into the journey of how textile printing evolved in India.

Origins

The earliest known evidence of cotton fibre was evacuated in Jordan and dated to 4450-3000 BC.

The earliest known evidence of cotton fibre was evacuated in Jordan and dated to 4450-3000 BC.

Given the early date, these fibres are most likely to have come from India.

The earliest evidence of textile printing dates to the Indus Valley Civilisation.

Archaeologists have uncovered remains of dyed cloth dating back to 1750 BC from Mohenjo-Daro, now present-day Sindh, Pakistan.

The analysis of the fragment of cotton attached to a silver jar indicated the presence of mordants used for permanent dyes.

Anuradha Kurma, Chief of Products (apparels), Fabindia, comments on Indian cotton fragments:

“The oldest record of Indian block print cotton fragments were evacuated at various sites in Egypt, Fustat near Cairo.”

It is believed that textile printing originated in Ancient China, when people started decorating cloth and paper using woodblocks carved with patterns and symbols.

Dye was applied to the woodblocks and then pressed onto the fabrics to create intricate designs. This technique spread through trade routes and cultural exchanges, reaching India and thereby influencing local textile practices.

Indigo was also one of India’s major dyes from antiquity until the mid-twentieth century, widely used both locally and for export.

Sources of indigo included Bayana and the Gujarati hinterland around Sarjek Cambay, and Sindh.

The political ramifications of indigo production in Bengal even affected India’s Independence Movement in the 20th century.

Expansion of Trade

Luxurious materials like silk were brought to Southeast Asia through trade with China and India. This influenced the manufacturing and development of elaborate, finely woven fabrics.

Luxurious materials like silk were brought to Southeast Asia through trade with China and India. This influenced the manufacturing and development of elaborate, finely woven fabrics.

Silk brocades were luxury textiles. The high cost of these fabrics made them symbols of prestige, and their use was restricted to the royal families, nobility and clergy.

Indian trade networks contributed to the spread of textile techniques, including ikat, batik, and tie-dye.

Ahmedabad flourished as a significant textile production hub, famous for its high-quality printed cotton. This was known as “chintz” in European markets.

Unlike other coloured cloth, the dyes on chintz would remain.

French bishop Pierre-Daniel Huet describes this as “as long as the cloth itself.”

Chintz cloths, like Chinese porcelain and tea, New World coffee, and chocolate, were produced in far-off realms that revolutionised the domestic interior and enlivened provincial daily life.

The ‘calico craze’ for Indian cloth began in the 1660s and died out only at the end of the 18th century when the Industrial Revolution formed the replacement of Indian cotton with British-made goods.

In the early 17th century, the British imported only negligible quantities of painted cotton textiles for home consumption, from 60 to 100 pieces a year.

Indian textiles played an important and historical role in the trade of Maritime Southeast Asia.

A unique Southeast Asian style based on the ikat method was born.

Gujarati weavers created patola specifically for the Indonesian market, applying techniques such as the double-ikat patola method.

Patolu refers to sarees created in Gujarat’s town of Patan. These sarees are recognisable by their rich, red colour and bold designs of small squares.

These are created by first tying and dyeing the warp and weft threads, then weaving the pre-dyed threads to reveal the full pattern.

Patola is used in India as bridal sarees and ceremonial textiles. This played a key role in the history of Indian textile exports to Southeast Asia.

In style, the figures and colours of the Gujarati textiles were distinct from the Deccani cotton paintings.

While the Deccani cotton paintings included a range of purples, pinks, and blues, the colours on the Gujarati textiles are confined to a rich, nearly black-hued blue, red, and white.

The Coromandel Coast cotton painting has curving, natural swatches of flowers and vines as patterning, while Gujarati patterning features a range of squares, dots, and diamonds.

Some well-documented examples of Gujarati textiles found on other Indonesian islands, particularly the highland interior of Sulawesi, inhabited by Toraja, show how big Indian trade was in the Middle Ages.

The spread of railroads across the subcontinent after 1850 allowed cloth from Lancashire, the centre of Britain’s textile industry, to reach villages in northern India.

The Classical Period

The classical period in India, broadly spanning from around 200 BCE to 1200 CE, experienced great advances in textile printing, particularly with the introduction of block printing.

The classical period in India, broadly spanning from around 200 BCE to 1200 CE, experienced great advances in textile printing, particularly with the introduction of block printing.

In early modern Central and South Asia, textiles were also an indicator of healthy governance, reinforcing the importance of cloth at the nexus of arts and politics.

Evidence from the early centuries (CE) suggests that block printing was a common practice, particularly in Gujarat and Rajasthan.

This era witnessed a confluence of diverse cultural influences, including indigenous traditions, and Buddhist and Jain philosophies.

The era also included interactions with trading partners from Central Asia, China, and the Mediterranean.

Artisans extracted colours from plants, minerals, and insects, creating a vibrant palette that included hues like indigo blue, madder red, turmeric yellow, and various shades of green and brown.

Pink, yellow, and red dyes made from flowers of saffron and safflower were known as ‘kaccha’ dyes, meaning temporary, raw, or unripe, and were prone to fade quickly.

These natural dyes not only produced rich, enduring colours but also aligned with traditional beliefs in harmony with nature.

Textiles acquired significant value as trade commodities and presents, which were exchanged as part of diplomatic interactions and cultural festivities.

Royal courts and wealthy patrons commissioned elaborate textiles for ceremonial occasions, religious rituals, and courtly attire, encouraging artisans to innovate and perfect their craft.

The invention of printing machines and the growth of cloth mills caused problems with printing by hand.

European designs and chemical dyes began to dominate the market, leading to a decline in the use of natural dyes and traditional motifs.

Even after factoring in the expense of transportation, foreign cloth costs 30% less than homespun, handloom-woven fabric.

Between 1850 to 1880, Indian cloth production fell by 40%.

Despite all these changes, some regions, such as Rajasthan and Bengal, managed to maintain their artisanal history by producing hand-printed textiles for both domestic and foreign markets.

While no surviving patterns from southeast India exist from the seventeenth century, John Irwin has suggested that Europeans brought paper pattern books from artisans to copy.

Physical patterns, or “musters,” as they were known in the English context, were in the possession of the East India Company.

The Mughal Influence

The Mughal Empire (1526-1857) made significant contributions to the advancement of textile printing.

The Mughal Empire (1526-1857) made significant contributions to the advancement of textile printing.

1550 to 1700 saw vast urban expansion, increased trade, and relative social and political stability.

Emperors like Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan supported the development of intricate craftsmanship in various forms, including textiles.

The empire’s capital cities, such as Agra, Delhi, and Lahore, became centres of textile production where skilled artisans from across the empire and beyond converged to create masterpieces.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Indian textiles flourished as a bartering currency at South Asian spice markets.

They were deposited in dowries and preserved as precious heirlooms in Indonesian, Malaysian, and Thai collections.

Under Mughal rule, textile design saw a synthesis of indigenous Indian techniques with influences from Persia, Central Asia, and beyond.

They promoted the use of sophisticated weaving looms, dyeing methods, and printing techniques that allowed for the creation of intricate designs with precision and finesse.

This influence and fusion led to the widespread use of delicate floral and geometric patterns.

Methods like Kalamkari, which requires drawing by hand with a bamboo pen and then dyeing it, became popular.

The intricate floral motifs introduced by the Mughals are still commonly used in the handblock-printed textiles of Rajasthan.

With the support of the Mughal imperial court and regional elites, the textile industry became the second-largest sector of the domestic economy after agriculture.

The Coromandel Coast

The region of Deccan, where Machilipatnam is located, boasted vibrant trade and cultural exchanges in the seventeenth century.

The region of Deccan, where Machilipatnam is located, boasted vibrant trade and cultural exchanges in the seventeenth century.

The Coromandel Coast was among the most politically turbulent areas, wrecked by war, droughts, governments in transition, and the nascent forces of European colonialism.

The independent sultanates of Deccan, including Golconda, Bijapur, and Ahmadnagar, operated both within and beyond the Mughal sphere of influence.

The Dutch Vereenidge Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) gained permission to trade in Golconda in 1606 and was allowed to conduct its commerce under decreased duties.

The East India Company (EIC) followed suit, establishing its presence in Machilipatnam in 1611.

The Portuguese, followed by the Dutch and the English, worked to solidify their trade outward from Machilipatnam, using it as a base for commerce with Southeast Asia, the Persian Gulf, and the Middle East.

The Coromandel Coast was known as the textile-producing region in India.

Finely woven cotton cloths with stunning hand-drawn motifs in a red and blue colour palette were produced along this trade-friendly coast.

The northern Coromandel Coast boasted superior chay roots. The thin shoot of roots carries only alizarin. These were used to create a concentrated, unadulterated crimson hue.

These chay roots grew best in the wild in the sandy soil of the local riverbeds of the Krishna delta.

The governor of Machilipatnam held an exclusive lease on land across the river from the town of Petaboli, where wild chay roots grew.

The demand for kalamkari textiles grew in Europe in the latter parts of the 17th century.

As a result, European East India Companies, and particularly VOC, sought to control the entire production of the Coromandel Coast’s kalamkari cloths.

Block Printing

Block printing is one of the most ancient craft arts in existence.

Block printing is one of the most ancient craft arts in existence.

It is believed that this method was introduced through early trade channels, possibly influenced by Chinese woodblock printing techniques.

Block printing can be found in endless possibilities, including clothes, bags, shoes, curtains, bedsheets, notebooks, and home décor.

Skilled artisans carve intricate designs onto wooden blocks, with each colour requiring a separate block.

The fabric is pre-treated through washing, bleaching, and sometimes mordanting to ensure even dye absorption.

The blocks are dipped in dye and pressed onto the fabric, starting with the outline and followed by filling in colours, with precise alignment for seamless patterns.

After printing, the fabric may undergo additional dyeing, and the final steps often include washing and sun-drying to set the dyes and achieve the desired finish.

Jaipur, known for its Sanganeri and Bagru prints, is a significant block printing centre. The skills of chhipa walla, the master dyers, go back generations.

Sanganeri prints are easily identifiable by their delicate floral designs on white or off-white backgrounds, while Bagru prints include earthy colours and geometric patterns.

Ahmedabad, another key centre, has a long history of textile manufacturing and block printing, generating a wide range of patterns and designs.

Issues

The craft also tackles many issues. Block printing is often more expensive than the textiles that machines produce.

Manual labour increases the time required to produce each piece, making it difficult to scale up production.

The process involves repetitive movements and long hours, which can lead to physical strain and health issues for artisans.

This, in turn, started affecting productivity and the overall well-being of workers.

In addition, the availability of natural colours and high-quality raw materials can vary, which can affect production.

The availability of these dyes can be inconsistent due to seasonal variations, agricultural yield, and environmental factors.

As a result, machinery and foreign cloth that were cheaper and faster gained popularity.

Despite the disadvantages, the art of block printing cannot be simply replicated by machines.

The uniqueness and intricate detail that come from the hands of skilled artisans lend a distinct character to block-printed textiles, which mechanical processes cannot fully capture.

This human touch gives each piece a unique feel and genuine quality, making it highly valued by people who love handmade products.

Kalamkari

The aforementioned Kalamkari is a traditional form of cloth painting that originated in South Asia, specifically India.

The aforementioned Kalamkari is a traditional form of cloth painting that originated in South Asia, specifically India.

This technique involves elaborate hand-painting or block printing on fabric with natural dyes. Kalamkari colours are made mostly from vegetable dyes.

The name ‘Kalamkari’ comes from the Persian words ‘kalam’ (pen) and ‘kari’ (craftsmanship). Kalamkari has a 3,000-year history, with origins in ancient temple art and sacred stories.

Originally, it was used to make temple hangings, scrolls, and narrative panels with mythological legends.

The detailed representations of gods, goddesses, and mythological scenes reflect the deep spiritual roots of the art.

The fabric, typically cotton or silk, is treated with cow dung, bleach, and myrobalan to ensure dye adherence. Common colours include indigo, red, and black.

In Srikalahasti, designs are drawn freehand with a bamboo stick, while Machilipatnam uses carved wooden blocks.

Natural dyes are applied in stages, followed by outlining details, multiple washes, and sun-drying to set the vibrant colours.

Srikalahasti in Andhra Pradesh is known for its delicate pen work as well as its freehand Kalamkari style.

This style became known during the Mughal Dynasty and was later adopted by the Golconda Sultanate. It is frequently used to show scenes from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata.

While Kanchipuram is renowned for its silk sarees, it also boasts a rich Kalamkari art legacy, especially in detailed border designs and motifs.

This blend of silk weaving and Kalamkari adds a distinct and elegant touch to traditional attire.

Kalamkari designs have been used to create a variety of products, including sarees, dresses, jackets, home decor, and accessories.

Ajrakh

Ajrakh is a traditional kind of block printing that has been used in South Asia for generations, particularly in Gujarat.

Ajrakh is a traditional kind of block printing that has been used in South Asia for generations, particularly in Gujarat.

It is known for its intricate designs and deep, rich colours.

The term ‘Ajrakh’ comes from the Arabic word ‘azrak,’ which means blue, a common colour in Ajrakh fabrics.

The craft is believed to have been brought to the Indian subcontinent by early Arab traders.

The fabric, usually cotton, is washed and soaked in camel dung, soda ash, and castor oil for softness.

Ajrakh uses resist dyeing, applying a resist paste to carved wooden blocks in multiple stages.

Natural dyes like indigo, madder root, turmeric, and iron acetate are used, with several rounds of dyeing, washing, and drying.

Finally, the fabric is washed again and sun-dried to set the colours and enhance durability.

The Kutch region is the heart of Ajrakh production in India. Ajrakh textiles from Kutch are known for their intricate geometric and floral patterns.

The intricate designs and laborious processes of Ajrakh make each piece a work of art. The patterns often carry symbolic meanings and reflect the rich history and artistry of the region.

Batik

Batik began in Indonesia, but its popularity spread across Asia, including India, through trade and social connections.

Batik began in Indonesia, but its popularity spread across Asia, including India, through trade and social connections.

It has been adopted and incorporated into culture throughout South Asia, particularly in India, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh.

Batik is a traditional textile art style known for its intricate patterns and bright colours created by a resist dyeing technique.

This textile is a powerful form of artistic expression in South Asia, with each region bringing its distinct style.

The patterns frequently include local culture, traditions, and natural surroundings, turning each piece into a work of art that tells a story.

In Kolkata, batik printing is known for its vibrant and artistic designs, often featuring floral patterns. This region’s batik textiles are used in garments and home decor.

The fabric, typically cotton or silk, is washed, prepared for dyeing, and then stretched on a frame.

Hot wax is applied in patterns using tools like brushes or stamps to create a resist that blocks dye.

The fabric is dyed with natural or synthetic dyes, with multiple layers of wax and dye.

Wax is removed by boiling, revealing intricate patterns and colours. The fabric is washed, dried, and ironed to set the colours and smooth out any remaining wax residues.

Other Regions

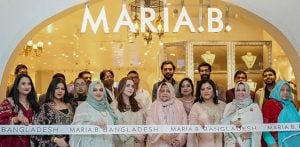

South Asia includes the countries of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka.

South Asia includes the countries of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka.

Dhaka, known for its Nakshi Kantha and block-printed textiles, produces fabrics that blend embroidery and block printing.

Jessore is another district in Bangladesh where traditional block printing can be found, mainly to make gorgeous sarees and home textiles.

Sindh, particularly Thatta and Hyderabad, is well-known in Pakistan for its Ajrakh textile production.

The designs are similar to those found in Kutch, including deep blue and red tones. Sindhi Ajrakh is traditionally used for shawls, turbans, and other items to represent cultural history and identity.

Batik is a popular art form in Sri Lanka, especially in Colombo. Sri Lankan batik is recognised for its vibrant colours and intricate designs, which frequently portray local flora, animals, and cultural aspects.

The textile printing sector in South Asia is not just an industry; it’s a vital economic pillar supporting millions of artisans and labourers, providing livelihoods and sustaining communities.

Craftspeople who have inherited their skills from previous generations continue to preserve these traditions.

In many regions, textile printing is a crucial source of income for women. In India alone, the handloom sector employs over 4.3 million people, with women making up 70% of the workforce.

Women usually work from home or in small groups, allowing them to balance work and family duties.

India’s textile printing industry thrives by combining traditional techniques with cutting-edge technologies.

Artisans explore new materials, designs, and environmentally friendly dyes, ensuring that the rich past of textile printing evolves while remaining relevant in a globalised society.

The global fashion industry’s emphasis on sustainability and ethical production has sparked renewed interest in traditional textile printing methods, leading to an endless legacy for the art.