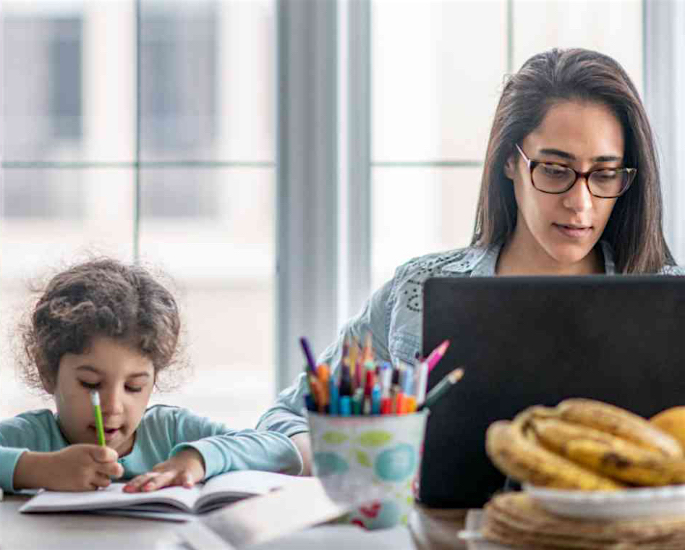

"You do feel that awful guilt that you’re missing out on their lives."

Balancing work and family can have a major impact on British Asian mums.

The complexities of managing professional and personal responsibilities are vast.

Consequently, mothers must undertake a careful and, at times, stressful balancing act.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) reported that 75.6% of mothers with dependent children worked in the UK between April and June 2021.

Three in four mothers with dependent children work in the UK.

Accordingly, the number of British Asian mums working by choice or necessity cannot be ignored.

Women often have multiple roles they must undertake.

Research has highlighted that women deal with a “triple burden” – undertaking emotional and physical labour at home, childcare, and paid work.

Speaking to mothers from Pakistani, Indian, and Bangladeshi backgrounds, DESIblitz explores the specific challenges British Asian mums face.

Childcare Arrangements

The nature of Desi families can be invaluable for childcare. Indeed, it allows for informal childcare arrangements with grandparents and extended family.

But for some Desi mums, informal childcare is not possible or desirable. Thus, formal childcare is a route they must take, but this also has its challenges.

Childcare can be an issue that results in clashes and tensions within South Asian families. It is often not just the parents who have views on what should occur.

Sonia*, a 36-year-old British Indian office worker and mother of seven-year-old twin girls, said:

“My parents freaked when we said we were putting the girls in childcare.”

“They were there and couldn’t understand why we wouldn’t let them care for the girls. They were confused by what they saw as us ‘wasting’ money, and hurt.

“We love my parents, but our parenting styles are very different. And some of our thoughts and ideas differ.

“We can afford it, so we decided it was the best route. And made sure we did our research.”

For Sonia, the instances where her parents had provided childcare resulted in arguments and clashes:

“I hated some of the things they were saying and teaching the girls. It was that traditional gender stuff I did not want them conditioned into.

“It led to arguments with me and my parents. And then me and my hubby fought. It was a mess and stressed me out.

“Then me and the hubby had enough. The first few months after, my parents were fuming.

“But it’s not like that for everyone. I have friends who would never consider going outside the family for childcare.”

Sonia relies on formal childcare for long-term family harmony and to ensure her children are socialised as per her and her husband’s preferences.

Informal Childcare Arrangements

For childcare, the role of grandparents and extended family can be invaluable.

Indeed, informal childcare through family members saves money and helps build and sustain family relationships.

Furthermore, within South Asian communities and homes, there can be distrust of formal childcare.

Shamima*, a 28-year-old British Pakistani teacher and mother of three, maintained:

“Without my family there to help, there’s no way I could work. And it would be me quitting if one of us needed to; husband earns more.

“I would never put them in daycare or have a babysitter. I’ve heard too many horror stories.

“I’m lucky both sides of our family live close and like helping with the kids. The kids have plenty of family time, and the money we save comes in handy.”

For Shamima, the close family network of childcare available to her is treasured.

Without her family providing informal childcare, she would be forced to stop working.

The fact that Shamima and not her husband would have to leave work due to his higher income matters. It partially reflects the ongoing gender pay gap. On average, men earn more.

Formal Childcare Arrangements

The need for formal childcare can be a heavy financial burden, with childcare costs having increased. However, some parents do not have a choice.

In 2024, the average cost of sending a child under two to a nursery for 25 hours per week (part-time) is £8,194 per year. In 2023, it was £7,729.

On average, a part-time childminder place is £6,874 per year in 2024, up from £6,547 per year in 2023.

Reva*, a 36-year-old British Indian community worker with two dependent children, stated:

“Both my husband and I work, and we just about scrape together enough for childcare. We have no choice; there’s no one here to help.

“We moved away from home, where we had family, because of work. And we can’t move back because of my husband’s work.

“So we lost out on having family help us take care of the children. My income, even though lower, is needed. Can’t afford to leave work.

“But we have talked seriously about both of us looking for work back where the families are. It would be easier.”

It’s clear that parents face many challenges as they navigate work and home life.

Dealing with Work Inflexibility

Hybrid and flexible working have become increasingly popular.

However, not all occupations allow flexibility. Instead, working hours can lead to stress and guilt for some Desi mums.

Sharon is a 43-year-old British Pakistani working as a police officer. As a mother, she has faced challenges both when with her partner and as a working single mother:

“It’s unsociable hours. With police officers, our times can just change.

“For example, when the Queen died. […] The footprint in London with the number of people coming in was ridiculously high. So, a lot more police presence was needed.

“Overnight, for two whole weeks, we were told to work 12-hour shifts. It didn’t matter what shift you were on; it had to be 12 hours. People’s rest days and everything got cancelled.

“It was one hour to get to work and one hour back to get home. So, I left the house for 14 hours.

“Who’s going to have children in between that time? You leave them when they’re asleep and come back when they’re sleeping.

“Even if I was with a partner, I wouldn’t see her. And it’s not just that, who will do your shopping, the day-to-day things?

“But they don’t care about your home life; there’s no help in any way.”

“I’ve gone on a flexible pattern because when I joined the job, I was with someone; during the job, life changed.

“It’s not how I planned it. I’m now a single parent working as a police officer. There is no childcare made around those hours.”

It is clear that welfare support for those like British Asian mums working in emergency services needs greater attention.

Sharon and her ex-partner have a good co-parenting relationship. He lives close by and can care for their daughter when Sharon is unexpectedly called into work.

However, not all mothers have a co-parent or family member to rely on. This raises the question of how many Desi mums have had to give up work they love, due to parenting responsibilities.

Challenges of Working from Home

There has been an increase in people working from home. The Covid-19 lockdown showed how much work can be done remotely.

Working from home can be invaluable, but it can bring various challenges for parents.

Iram*, a 37-year-old British Pakistani, recalls working from home during the Covid-19 lockdown:

“My kids were four and six during the lockdown. They didn’t get mummy was working from home and couldn’t be disturbed.

“If not for my husband being home and taking care of the kids, I don’t know what I would have done.

“It showed me I wouldn’t want to work with the kids underfoot at home. I love them, but no.”

“I also didn’t like the blurring of work and home. Plus, I like socialising at work too.

“The office is good for me, and hybrid is fine, but completely working from home is not happening by choice.”

For parents like Iram, going out to work can be essential to keeping a healthy work-life balance.

Ruby*, a 26-year-old British Bangladeshi, has a 3-year-old daughter named Maya*. Both she and her husband work from home:

“We’re blessed our work schedules are flexible and fit around Maya. When he is working, I’m looking after her; when I am working, he is looking after her.

“It would be a nightmare if we didn’t have each other. She wouldn’t get the attention and educational support she needs.”

Juggling Housework and Paid Work

A great deal has changed in South Asian communities. However, there is still a traditional and highly gendered expectation of who does housework.

Cultural expectations around women’s roles have widened, for example, working outside the home.

Yet there remains an expectation that women should be able to undertake paid work and still care for a family and home.

Such expectations are made worse because childrearing and housework are not seen as forms of work comparable to paid work.

Thus, Desi mums can face pressure to juggle home and work responsibilities.

Alina*, a 29-year-old British Pakistani nurse, said:

“My in-laws expected me to work, take care of the kids, them, the house and cook.”

“When Malik* [husband] helped, my mother-in-law was disgusted saying ‘men don’t do housework’.

“It led to tension we didn’t need. Eventually, we moved out. We both work, and he helps with the housework and cooking.

“It frustrates me that it’s just expected for Asian women to do everything.

“If a guy does it, some either think, ‘Oh wow, you’re so lucky’ or ‘What’s wrong with her that she can’t do it’.

“But me cooking, looking after kids, and cleaning, no one blinks, it’s just expected. Ridiculous that it still happens.”

There continues to be a need to shatter traditionalist ideas of housework and childrearing. Nevertheless, it appears things are changing within some Desi homes.

Dealing with Feelings of Guilt

Working Asian mums can feel profound guilt for not spending more quality time with their children and family.

Sharon stated: “You do feel that awful guilt that you’re missing out on their lives.

“Obviously, it’s a long day for them. They’re at school, and then after-school clubs and whatever.

“By the time you’ve grabbed them and fed them, it’s bedtime, and that’s it. You’ve not been able to spend any sort of quality time with them at all.”

For Iram, working is a vital part of her identity, without which she would struggle:

“I know myself. I couldn’t be a stay-at-home mum.

“Sometimes I feel guilty… sometimes, and I wonder if that’s too selfish.”

“Some women love it; for me, it would be torture. Kids have a happy mummy right now, but it would be a different story if I didn’t have work and that break.

“The mummy they would have would be unhappy, and that would negatively impact them and my husband.”

Parental guilt over working and not being with children can be a significant issue.

Yet, working is often needed for numerous reasons, from financial necessity to maintaining a sense of self outside of children and the home.

Challenges of Making Time for Other Relationships

Between work and the responsibilities of children, it can be difficult for Desi mums to spend time on other relationships.

Indeed, Alina stressed: “Running between work, kids and home, I did forget to touch base with friends.

“Me and the Malik stopped doing things. When we first got married and before, we made an effort to do things together, just us.

“But as months turned to years, we forget in the daily grind. One day I realised what had happened, I didn’t like it and we spoke.

“We make an effort to give each other time, even if it’s just curled up on the coach.”

“It helps that we have family close that the kids can spend time with. We do the same for our cousins; we look after their kids so they can have some alone time.’

Similarly, Sonia stated: “The first few years with the girls, my hubby, work and life, I did let friendships slide. I didn’t mean to, but my attention was all taken up.”

Sonia then highlighted the importance of self-care: “I stopped doing things for me. As Asian mums, mums in general we forget how much it matters to take care of ourselves.

“For our kids, family and health it’s important that we find time to relax. Although that can feel impossible at times.”

Desi mothers often juggle multiple responsibilities and challenges, including caring for their children, working, and maintaining other relationships.

As traditional norms and expectations within South Asian communities have widened, Desi women have had the opportunity to do more.

Yet, it remains true that some traditional cultural expectations, such as those regarding housework, can cause tension within the wider family.

Accordingly, working Asian mothers face complex challenges as they strive to balance their professional and personal lives.