The teenager suffered in silence until the age of thirteen when she asked for help.

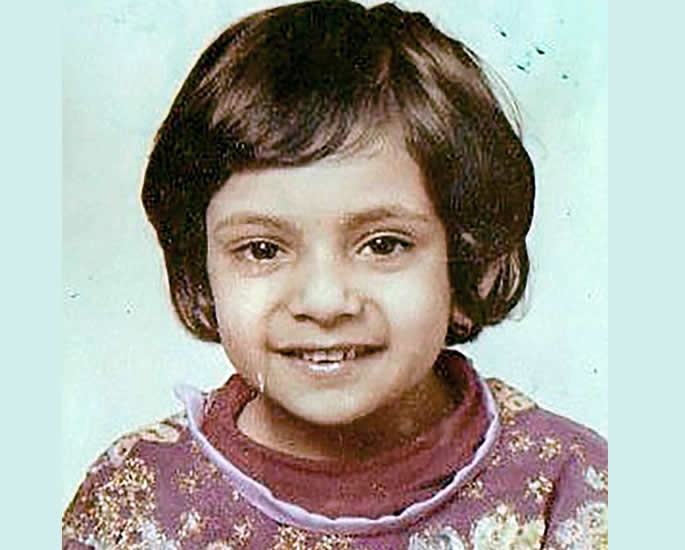

Sabah Kaiser, aged 43, of Bristol, has shared her story of being sexually abused in her own home since the age of seven.

She waived her anonymity on Friday, August 25, 2018, to inspire others to come forward.

Originally from Pakistan, Sabah’s family moved to Britain during the 1970s after her father served with the British Army.

They settled in Bristol.

Sabah was raised as a child in a house Montpelier along with her 17 brothers and sisters.

Sabah went to a school n Eastville and enjoyed what appeared to be a normal childhood.

But behind closed doors, Sabah was being sexually abused and mistreated.

Despite knowing what was happening to her was wrong, Sabah felt powerless to prevent it.

She struggled against a language barrier, her family and a strict cultural upbringing.

Now a mother of two, she has waived her anonymity to shatter the stigma around hidden sexual abuse in British Asian families.

Sabah’s Story

Talking about her trauma from a young age, Sabah said:

“From the age of seven, I was initially abused by what I would refer to as my main abuser.”

Her main abuser was part of a paedophile ring which operated from her outwardly respectable family home.

The teenager suffered in silence until the age of thirteen when she asked for help.

However, within a strict Pakistani household, Sabah’s family refused to acknowledge sex or allow it to be discussed.

This made it difficult for her to properly communicate what was happening.

She admitted:

“I didn’t know the words for my body parts.”

“In fact, some of my body I still do not know the words for in my language and I’m an interpreter.”

Between the ages of seven and 16, Sabah Kaiser was taken advantage of and sexually abused by several men visiting her home.

One incident involved a relative insisting that she strip naked and massage his legs before sexually assaulting her.

When the ordeal was over, his wife stripped off the bloodstained sheets in front of a confused Sabah.

The woman told her:

“You have wet the bed. If you tell anyone, you’ll be in big trouble.”

The taboo subject of sexual abuse in a Pakistani community meant that people were aware of it but never said anything.

“My community were silent perpetrators, standing in the shadows, knowing what was going on and saying nothing.”

“There is a shame surrounding it, yet I feel that the men – under the culture and under the belief – think they are a higher, more valued, more important sex than women are.”

Sabah added: “We are, in my experience, considered as property and so property to do [with] what they want.”

Asking for her Mother’s help

Sabah attempted to speak out against her abusers by telling her mother.

But despite her mother challenging one of the abusers, he denied the allegations and blamed Sabah for “saying things she wouldn’t dream of saying” in Pakistan.

“I remember telling her what happened.”

“She asked him a question as if she was just asking him ‘did you eat the last chapatti’?

“It was so casual. ‘Did you touch my daughter?’ was the question.

“He was asked the question and he went into a barrage of how I had no respect for my elders.”

Exposing the Abuse

Sabah’s abuse at home was finally exposed after she took the courage to spoke of her ordeal to friends and a deputy-head teacher, who subsequently contacted the police and social services.

The deputy-head teacher she saw as a father figure and said he was “always looking out for me”.

Sabah bounced tennis balls in the school corridor numerous times to get the attention she wanted.

Many times the balls were just confiscated but then eventually the deputy-head teacher told her to come into his office and said:

“Right Sabah come in here and tell me what it is you are trying to tell me.”

It was after this conversation that the school were told about the abuse and “the police interview happened and the social services came in.”

She was asked by one of the police officers in the interview at school:

“Did he have intercourse with you?”

At the age she was, Sabah “did not know the word” or the “meaning of it”.

The police officer said to her if she “did not know what the word meant”, then it could “not have happened” to her.

After this point, social services became active and took her into care. Sabah stayed in care until she was “an adult”.

Continued Abuse

Sabah thought that her abuse was over, however, it continued, but now by a different perpetrator.

The deputy-head teacher had been “asked by the school, by the heads, to counsel” her for the sexual abuse Sabah experienced as a child.

He invited her to his office and Sabah recalls:

“Initially he just wanted to hear a lot of detail, and then the abuse began.”

“It was two years it continued for.”

It was not until “another girl had spoken up about it” that other pupils “stepped up” and came forward to report the staff member.

He was dismissed from school and taken to court.

Blaming Herself

Realising it happened so quickly, Sabah says:

“It was taken seriously. Everybody believed it. But for me, my failure compounded it. It made it worse.”

As this was her second experience as a victim, Sabah started to think that she was to blame.

“For me, I was convinced that at that age, again, still a child, that there’s something wrong with me.

“That I am the one one that causes this to happen. That it’s not actually their fault.

“In fact, I was insisting that it wasn’t his fault. That is was my fault.

I insisted that to the police and I insisted that to my teachers.

“It’s only now that I know it was his fault, but at the time, I didn’t believe that.”

However, by now Sabah’s “trust had completely gone.”

By the time it came to her court case, she did not attend, despite people believing her. She says:

“I was so scared. As a child, I felt that I was going to get found out. That the judge would see that it’s all my fault.”

She feels things have changed in this respect today, where people can give evidence with support but back then she was very afraid of the whole process.

Desi Culture’s Problem

Sabah feels her culture has a very important role to play when it comes to dealing with sexual abuse due to the taboo, saying:

“In my experience, my culture cloaked it. It protected it.”

“And that’s because the bigger issue, the macro issue isn’t me, it’s how we are seen in the public, in the community.

“And I’m a woman, I’m a girl, and sex is something that’s absolutely under any circumstances not discussed.”

She feels she cannot reconcile the two things as a woman.

Speaking about her mother, who passed away, she says:

“I love my mum and I know she loved me. I forgave her long before she died. I refuse to allow hatred to dwell in my heart because I am only hurting myself.”

Sabah decided to cut all the ties with her family many years ago.

Impact of Abuse

Revealing how the trauma and experience of being sexually abused as a child at home and then at school has impacted her, she says:

“I can’t remember a time, I haven’t woken up scared. I can’t remember a time when I haven’t gone to sleep scared.

“Because I feel that people like me, we’re kinda, we’ve been damaged and broken. We were never

“We were never repaired when we were meant to be repaired. We were failed.

“Then you grow up with that failure becoming yours. It should’ve been theirs but it ends up becoming yours.”

She feels coping to survive as a victim of child abuse is very difficult as it stays with you forever, saying:

“I just wish someone could tell me how to live because I don’t know what that means.

“You don’t know where you belong. You don’t know where you came from. You absolutely have no idea where you are going.”

She feels now she has the right to be angry and not feel scared and can give the “failure back to them”.

Today, Sabah is using her horrific and dark ordeal as a child to inspire others to come forward like she did and tell their stories as realities.

She is a supporter of an organisation known as the Truth Project, which invites victims and survivors of child sexual abuse to discuss their ordeal with specialist support staff.