"This is nothing but a form of collective murder."

Throughout the past century, India has continuously revised its laws to protect Indian women. The laws have been modernised and reformed to better the rights of women.

Mahatma Gandhi, who imparted a strong sense of personal ethics, believed in the equality between women and men.

He said, “I passionately desire the utmost freedom for our women.”

Gandhi firmly asserted that India’s salvation is completely dependent to the sacrifice and enlightenment of Her women.

He referred to his mother country as a female.

Since 1956, numerous laws have been enacted and are constantly reviewed, giving the opportunity to Indian women to finally receive equality between females and males.

DESIblitz reviews women-specific legislation in India. The first is the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act 1956.

The Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961

The Dowry Prohibition Act was introduced in 1961 to prohibit any party from giving or taking dowry.

Often, ‘dowry’ is the property or money brought by a bride to her husband on their marriage. In this way, women obtain financial security but also maintain independence after marriage.

In the Act, the term ‘dowry’ is defined as means any property or valuable security given or agreed to be given either directly or indirectly:

- By one party to a marriage to the other party to the marriage; or

- By the parents of either party to a marriage or by any other person, to either party to the marriage or to any other person;

- At or before [or any time after the marriage].

However, the dowry system can lead to numerous crimes, including emotional and physical abuse, deaths, and other related crimes to Indian women.

A case of dowry resulted in a woman being burnt because she denied the cash demanded by her husband after he took 1kg of gold from her family.

The police are forced to investigate complaints before beginning a court trial.

Counsellors from a women’s helpline said that:

“(actual) cases are probably fewer because we find several women trying to blackmail their husbands and in-laws.

“Recently, we had a wife who had been threatening the husband of pouring kerosene on herself for 10 months out of displeasure over her mother-in-law.

“When she approached us, she made the case seem as if it was a dowry case when clearly it was just disagreement among them.”

However, “attacks on women who are victimised by the socio-economic menace” have suddenly dropped in number in 2020.

As a matter of fact, 2019 saw 739 cases with 52 deaths, which fell drastically to only 17 dowry cases and no deaths in 2020.

“The counsellor added that such cases may see a dip this year compared to last year with more stringent checks being employed,” but these facts appear to be questionable.

Kavya Sukumar wrote a first-person essay and talked about the time where she had to choose what to do with half a million dollars.

When she was younger, she and her sister would always play a game, where they asked themselves what they would do with approximately 1,500 in dollars.

They were both told by the aunt that they “ought to save the money for our dowries instead of wasting it on ‘useless things’.”

However:

“This time the stakes were higher, the money was not imaginary. We were asking ourselves what we would do with half a million dollars.

“We had to pick between Srini’s dream of us retiring in our 40s and paying my sister-in-law Priya’s dowry.”

Sukumar explained:

“The amount [of dowry] depends on a large number of factors, including region, religion, caste and subcaste, groom’s education, bride’s skin tone, and the negotiation skills of both the families involved.”

She noted that more often than not, it is not reported as a crime and said:

“Dowry gets reported only when the groom’s demands go beyond what the bride’s family can afford or when the bride is physically abused or, worse, killed.”

Over 7,600 of 113,000 reported cases of domestic abuse are:

“Classified as related to dowry disputes.

“That is nearly 21 women killed every day by their husbands or in-laws because their families could not meet the dowry demands.”

From personal experience, Sukumaru discussed:

“Instead of being regarded as a crime and a source of shame, dowry has become a matter of pride.

“It is not as discreet as one would expect with an act of illegal transfer of assets.

“It is flashy and in your face. It is discussed over coffee at family gatherings.

“Sons-in-law are often introduced with the price tag they come with.”

This is why if any person gives or takes or abets the giving or taking of dowry, he shall be punishable:

With imprisonment for a term which shall not be less than five years;

And the fine shall not be less than fifteen thousand rupees or the amount of the value of such dowry, whichever is more.

Such penalties are given to protect the rights of Indian women for a safe and fair marriage. Any agreement for giving or taking dowry shall be void.

Dowry is therefore prohibited unless it is for the benefit of the wife or her heirs:

Any dowry received by any person other than the woman in connection with whose marriage it is given, that person shall transfer it to the woman.

And pending such transfer shall hold it in trust for the benefit of the woman.

In the case where the entitled woman (to any property) dies before receiving it, her children (‘heirs’) are entitled to claim it.

However, if any person fails to transfer any property, he shall be punishable with:

- Imprisonment for a term which shall not be less than six months, but which may extend to two years; or

- Fine [which shall not be less than five thousand rupees, but which may extend to ten thousand rupees]; or

- Both.

Therefore, the Dowry Prohibition Act was passed to prevent brides from having to pay significant amounts of money to obtain security and maintain independence.

However, this is still a prevalent problem in India.

According to globalcitizen.org:

“More than 8,000 women die as a result of India’s dowry system each year.

“Sometimes a woman is murdered by her husband or in-laws when her family can’t raise the requested dowry gift.

“Other times, women commit suicide after facing harassment and abuse for failing to meet the dowry price.”

However, “just a third of reported dowry-motivated murders result in convictions.”

A women’s rights worker spoke to the Pulitzer Centre about the violence that follows after the conditions of the dowry are not met, saying:

“The violence ranges from brutal beatings, emotional torture, withholding money, throwing them out of the house, keeping them away from their children, keeping mistresses openly, or in extreme cases, ‘burning the wife alive’.”

The Dowry Prohibition Act was finally passed in 1961, to protect women from such extreme, radical, and horrific acts, which could lead them to death.

The Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987

The commission of sati consisted in the sacrifice of a widow, who would throw herself onto the husband’s pyre as part of his funeral ceremony, burning to death.

In this Act, the term ‘sati’ is defined as the act of burning or burying alive of:

- Any widow along with the body of her deceased husband or any other relative or with any article, object or thing associated with the husband or such relative; or

- Any woman along with the body of any of her relatives, irrespective of whether such burning or burying is claimed to be voluntary on the part of the widow or the woman or otherwise.

An activist named Kushwaha affirmed that women commit sati because they are coerced to do so.

Kushwaha said:

“This is nothing but a form of collective murder.”

A resident named Bal Kisan was asked the reason why sati still existed, despite becoming illegal in 1987 due to the Prevention Act.

He answered, “Aashta hai”, which means “it is called faith.”

Linda Heaphy explained:

“Historically, the practice of sati was to be found among many castes and at every social level, chosen by or for both uneducated and the highest-ranking women of the times.

“The common deciding factor was often ownership of wealth or property since all possessions of the widow devolved to the husband’s family upon her death.

“In a country that shunned widows, sati was considered the highest expression of wifely devotion to a dead husband (Allen & Dwivedi 1998, Moore 2004).

“It was deemed an act of peerless piety and was said to purge her of all her sins, release her from the cycle of birth and rebirth and ensure salvation for her dead husband and the seven generations that followed her (Moore 2004).”

However, nowadays the attempt of committing sati is punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to six months or with fine or with both.

The court has to take into consideration the circumstances leading to the commission of the offence and the state of mind of the charged person.

However, if sati is committed, then whoever abets the commission of such sati, either directly or indirectly, shall be punishable with:

- Death; or

- Imprisonment for life; and

- Shall also be liable to a fine.

In fact, even the glorification of sati is punishable. Whoever does any act for the glorification of sati shall be punishable with:

Imprisonment [no less than 1 year to 7 years]; and

Fine [no less than 5,000 rupees to 30,000 rupees].

But in the past, widows voluntarily committed sati.

Richa Jain explained:

“Sati symbolised closure to a marriage.

“It was, therefore, considered to be the greatest form of devotion of a wife towards her dead husband.”

The practice became forced later on, since:

“Traditionally, a widow had no role to play in society and was considered a burden.

“So, if a woman had no surviving children who could support her, she was pressurised to accept sati.”

Heaphy writes that as the practice of sati stopped being tolerated and the truth became obvious, widows attempted to escape that tragic and painful ending.

Most of them did not.

According to Heaphy, Edward Thompson wrote that a woman “was often bound to the corpse with cords, or both bodies were fastened down with long bamboo poles curving over them like a wooden coverlet, or weighted down by logs.

“These poles were continuously wetted down to prevent them from burning and the widow from escaping (Parkes, 1850).”

The last known case of sati was of Roop Kanwar, an 18-year-old girl who arguably voluntarily committed sati after her husband passed away from illness.

After the trial became public, “45 people allegedly held an event glorifying sati.”

This violated the law.

This is the same law “that was enacted after Roop Kanwar’s death.”

Anand Singh, a relative of Roop Kanwar, said:

“Thousands stood guard with swords as she approached the pyre.”

Anand continued:

“She sat on the pyre with her husband’s head in her lap. And she recited the Gayatri Mantra with one of her hands raised, blessing those who had gathered there.”

However, it is still to question whether the choice was hers, or if she was coerced.

This case is an example of modernity vs. tradition.

Heaphy discussed sati further:

“Kanwar’s sati led to the creation of state-level laws to prevent the occurrence and glorification of future incidents and the creation of the central Indian government’s The Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act 1987.

“However, of the 56 people charged with her murder, participation in her murder or glorification of her murder during two separate investigations, all were subsequently acquitted.”

Therefore, the Commission of Sati Prevention Act was passed in 1987 in order to avoid and prevent women from the commission of such act, which leads to a tremendous finale.

However, Hamza Khan mentioned:

“Even after all these years, there is no doubt in anybody’s mind that Roop Kanwar’s was a “selfless act” driven by “agad prem (unparalleled love)”.”

Being a bystander of sati is still illegal. Despite laws to prevent sati, it continues.

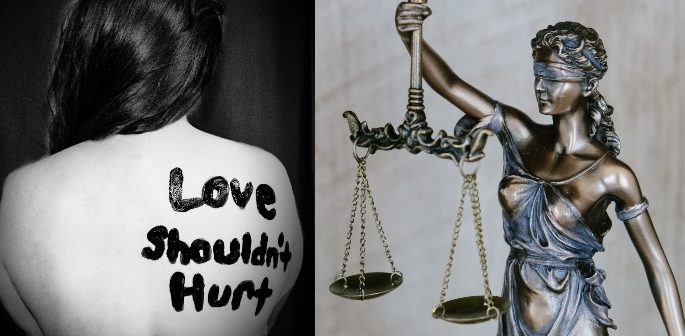

The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005

It was only this century that an Act to provide for more effective protection of the rights of women was introduced.

Section 3 of the Act defines ‘domestic violence’ as any act, omission or commission or conduct of the respondent shall constitute domestic violence in case it:

- Harms or injures or endangers the health, safety, life, limb or well-being, whether mental or physical, of the aggrieved person or tends to do so and includes causing physical abuse, sexual abuse, verbal and emotional abuse, and economic abuse; or

- Harasses, harms, injures, or endangers the aggrieved person with a view to coerce her or any other person related to her to meet any unlawful demand for any dowry or other property or valuable security; or

- Has the effect of threatening the aggrieved person or any person related to her by any conduct mentioned in the conditions above; or

- Otherwise injures or causes harm, whether physical or mental, to the aggrieved person.

Joe Wallen of the Telegraph said:

“Indian society is inherently patriarchal and domestic violence has become normalised – over half of boys said a husband would be justified in beating his wife, according to a UNICEF study in 2012.”

The Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health found:

“Gender-based violence against women is an important public health problem, which claims millions of victims worldwide. It is a notable human rights violation and is deeply rooted in gender inequality.”

The National Health of India writes that:

“It needs to be taken note of that during the period of the four phases of the lockdown women in India filed more domestic violence complaints than recorded in a similar period in the last 10 years.”

With the lockdown caused by COVID-19, the situation of victims of domestic violence has worsened. The BBC published Tara’s story, who said that “the lockdown changed everything.”

The BBC spoke directly with Tara.

Tara said:

“I live in a constant state of fear – of what could affect my husband’s mood.”

According to the BBC, Tara spoke “over the phone in a low voice after locking herself up in a room so her husband and mother-in-law wouldn’t hear her.”

Tara discloses her treatment:

“I am constantly told I am not a good mother or a good wife.

“They order me to serve elaborate meals, and treat me like a domestic worker.”

In another case of lockdown abuse in India, Lakshmi discovered that her husband had been in contact with a sex worker, she reported it to the police in fear that she and the children would contract COVID.

She told the BBC that she thought it was over, but her husband was only given a warning and beat her when he came home.

Lakshmi thought “they would register a complaint and arrest him.”

Instead, the police asked Lakshmi to leave.

Viiveck Varma, founder of domestic abuse support group Invisible Scars, told the BBC:

“Most of the time, women don’t want to leave an abusive spouse – they ask us how to teach them a lesson or make them behave better.”

This is largely due to the stigma of divorce in India.

Women are encouraged to stay in marriages even if their husbands are abusive.

Lockdown adds another difficulty.

Transport is limited so women in abusive relationships struggle to go to a shelter or even stay with their parents.

Section 10 of The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act focuses on the protection of women’s rights in any lawful way.

This includes providing legal aid, financial and medical aid as well as providing legal aid, medical, financial, or other assistance.

The responsibility of this aid falls upon the State Government.

The State Government help by:

- Reporting and investigating the crime;

- Providing medical care if needed; and

- Ensure shelter.

Therefore, the court does provide help for the women suffering domestic violence.

The British Medical Journal (BMJ) published details regarding Indian women who suffered partner violence.

The BMJ said:

“The responses show that nearly one in three women in India is likely to have been subjected to physical, emotional, or sexual abuse at the hands of their husbands.

“Physical violence was the most common form of abuse, with nearly 27.5% of women reporting this. Sexual abuse and emotional abuse were reported by nearly 13% and nearly 7%, respectively.”

Despite these figures, partner violence is underreported.

Social media has captured some of the domestic violence and left the world shocked.

However, many Indian attitudes remain unchanged.

Smita Singh provides an example:

“Social media was flooded with an appalling video clip of a man thrashing his wife.”

The wife of a Director-General, Sharma, caught him committing adultery.

She confronted him.

He ended up as the lead character in “a viral video clip where he was seen beating his wife.”

After his son accused his father of domestic violence, Sharma was immediately fired.

But the words he spoke to the journalists left the world stunned.

Sharma said:

“I have not indulged in any violence. This is a matter between my wife and myself. She complained against me earlier too in 2008. We have been married for 32 years.

“She is living with me and enjoying all the facilities and even travelling abroad on my expense. The point is if she is upset with me, why she is living with me.”

He added:

“If my nature is abusive, then she should’ve complained earlier.”

Sharma continued:

“This is a family dispute, not a crime. I am neither a violent person nor a criminal.”

Smita Singh commented:

“Men never seem to amaze me, no matter which social strata they belong to, the mind-set remains the same. They still consider women ‘their property’ to ill-treat, to beat, and to do as they please.”

Therefore, The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act was passed in 2005.

This law to protect Indian women covers domestic violence of any kind – physical or mental.

In this way, Indian women are encouraged to report these offences.

The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace Act, 2013

This law to protect Indian women was established to provide protection against sexual harassment of women at the workplace and for the prevention and redressal of complaints of sexual harassment.

The law defines ‘Sexual harassment’ as:

- Physical contact and advances; or

- A demand or request for sexual favours; or

- Making sexually coloured remarks; or

- Showing pornography; or

- Any other unwelcome physical, verbal or non-verbal conduct of sexual nature.

Bhankwari Devi’s case was a horrifying demonstration that women in India need this law to protect them.

Devi was gang-raped by high-class neighbours in 1992.

Bhankwari Devi was a government social worker and was raped due to trying to stop a child marriage in her neighbour’s family.

Those accused of rape were acquitted and served short jail sentences for lesser offences.

Devi’s employer “denied responsibility because she had been attacked in her own fields.”

28 years later, the appeal for Devi’s case is still pending in the High Court.

Public outrage has ensued for laws to protect Indian women against sexual harassment in the workplace.

As a matter of fact, Human Rights Watch confessed that women:

“Chose not to report sexual harassment to management because of stigma, fear of retribution, embarrassment, lack of awareness of reporting policies, or lack of confidence in the complaints mechanism.”

In numerous cases, the committee which is supposed to investigate complaints:

“Had failed to intervene because the accused was their supervisor.”

This is why some allegations are never proved.

In the case that the allegations of sexual harassment in the workplace are proved to be true, then the District Officer may:

- Take action for sexual harassment as misconduct;

- Deduct from the salary or wages of the respondent such sum it may consider appropriate to be paid to the aggrieved woman or to her legal heirs.

Section fifteen of the law decides how much compensation is awarded and is determined by:

- The mental trauma, pain, suffering, and emotional distress caused to the aggrieved woman;

- The loss in the career opportunity due to the incident of sexual harassment;

- Medical expenses incurred by the victim for physical or psychiatric treatment;

- The income and financial status of the respondent;

- Feasibility of such payment in a lump sum or in instalments.

To protect the aggrieved woman and all those involved in the case, all information is kept confidential.

If any information is made public, a penalty will ensue.

According to Human Rights Watch:

“The Indian government’s failure to properly enforce its sexual harassment law leaves millions of women in the workplace exposed to abuse without remedy.

“The central and local governments have failed to promote, establish, and monitor complaints committees to receive complaints of sexual harassment, conduct inquiries, and recommend actions against abusers.

“The Indian government should stand for the rights of women […] to work in safety and dignity.

“The government should coordinate with workers’ organisations and rights groups to address sexual harassment and violence as a key workplace issue, partner in information campaigns, and ensure that those who face abuse can get the support and remedies they deserve.”

However, a female domestic worker has admitted to the Human Rights Watch, “that sexual harassment in the workplace has become so normalised, [that] women are simply expected to accept it.”

In particular, “the factory worker, the domestic worker, the construction worker, we have not even recognised the fact that they are sexually harassed and assaulted on a daily basis.”

That was said Delhi-based lawyer Rebecca John because 95% of Indian women work in the informal sector, where “everyone thinks of harassment as trivial.

“Activists said that women still find it difficult to report because of stigma, fear of retribution and because they fear a drawn-out justice process that often fails them.”

The introduction of the Vishaka Guidelines in 1997 was commented by the court, which said:

“Gender equality includes protection from sexual harassment and right to work with dignity, which is a universally recognised basic human right.”

“However, the guidelines failed to explicitly address sexual harassment of women in the informal sector—a group now numbering some 195 million.”

Therefore, this law was passed in 2013 in order for the workplace to become a safe environment for every employer, without inequality and injustice.

However, there is still a very long way to go.

In conclusion, from 1956 until today, numerous laws have been inserted and are constantly reviewed, modernised, and reformed to better the rights of women in India.

It is questionable what changes need to be made in order to alter the horrific statistics of abuse women suffer in India.

However, the status of women has varied throughout Indian history.

There are many laws to protect women in India.

The constitution in India has awarded women equality and freedoms whilst offering help and support in maintaining these rights.

The problem may not lie in the laws to protect women but rather underreporting and societal attitudes towards women by and large.