"the JobCentre said ‘that’s not enough, we need more evidence of work'."

Economic abuse, which is recognised as a form of domestic abuse, involves the control of money, finances and things that money can buy.

It often occurs in the context of intimate partner violence.

While physical violence is frequently the visible face of domestic turmoil, economic control operates as a silent, suffocating trap for millions across the UK.

For British South Asian women, this form of coercion is often intertwined with cultural expectations, immigration status, and transnational complexities that mainstream support systems fail to understand.

Data suggests that minority ethnic women face economic abuse at twice the rate of their white counterparts.

We delve into the systemic and cultural mechanisms that leave South Asian women financially paralysed and highlight the devastating ripple effects on the next generation.

The Burden on South Asian Women

The gap in experiences of financial control is stark and deeply troubling.

A study found that minority ethnic women face economic abuse at more than twice the rate of white women, at 29% compared with 13%.

The findings reveal a disturbing pattern of financial dependency deliberately created within marriage to enforce compliance.

Two-thirds of the participants had been financially dependent on their husbands during their marriages.

This mirrors wider employment statistics for British Pakistani and Bangladeshi women, but low employment is often not a matter of choice. It is frequently a tool of control.

Several women described husbands actively preventing them from working to maintain dominance. When some did manage to earn, it was often in secret and driven by desperation.

UK-born Afsana worked covertly as a tutor for very little pay:

“This tutoring was undercover with my dad. My working would have looked bad on [my husband].”

Her experience highlights the intense cultural pressure to maintain the image of the ‘good wife’ who does not need to work, even when the reality is financial deprivation.

This control often continues beyond the marriage itself. After separation or divorce, many women are left economically exposed and pushed into a labour market that penalises them for gaps in their employment history, despite those gaps being created through abuse.

Due to limited experience and discrimination, some women struggle to secure work.

One woman told The Conversation: “I worked in one school as a volunteer, but the JobCentre said ‘that’s not enough, we need more evidence of work’.

“I said, ‘everywhere you apply, they ask for a qualification, and experience is the main thing’.

“I was not going out… how could I have undertaken any work?”

This feeds a damaging cycle of poverty and it represents a systemic failure that leaves South Asian women trapped between cultural coercion and economic exclusion.

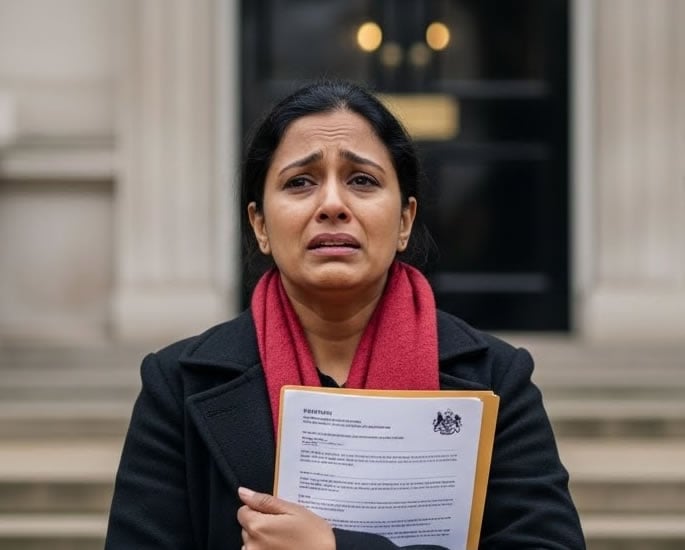

Institutional Failures

When South Asian women attempt to seek justice or financial support through state institutions, they frequently encounter a system ill-equipped to handle the complexities of their lives.

A major theme in the research was how abusers used child maintenance as a means to control women economically.

In 18 cases, the father was not paying any child maintenance at all. Of the remainder, only two mothers felt the amount was fair.

For many, the Child Maintenance Service (CMS) proved to be a blunt instrument against a complex problem.

This is particularly evident in transnational marriages where the husband holds significant assets overseas, in Pakistan, India, or Bangladesh, while declaring a low income in the UK.

Many abusers are self-employed, allowing them to manipulate their declared income, making it difficult for the CMS to investigate effectively.

Where women had involved the CMS, they felt it was unresponsive, especially those in transnational marriages involving economic assets overseas.

Kiran described her experience with CMS after her ex-husband hid assets in Pakistan:

“I’ve even given the telephone numbers and addresses in the properties which are in Pakistan. [But] ‘Excuse me. We know that you’re upset. It just takes a bit of time’. I go, ‘How long does it need?’”

This bureaucratic inertia sends a damaging message: the women are not believed.

Although the CMS faces jurisdictional limits in investigating finances held abroad, the dismissal of evidence provided by the women undermines their confidence in the system.

When a woman provides specific details of property and wealth abroad, and the state refuses to act because those assets are outside UK borders, the state effectively sanctions the abuse.

The women in the study described child maintenance mirroring earlier patterns of economic abuse during their marriages.

As Afsana put it: “He didn’t provide when he was with me, so I didn’t expect him to provide when he was not with me.”

The Weaponisation of Immigration

The intersection of British law and religious practices creates specific “blind spots” that perpetrators of economic abuse exploit.

Post-separation economic abuse occurs through institutions like courts and banks, where the nuances of South Asian matrimonial dynamics are often misunderstood.

A striking example of this is the misuse of religious marriage laws to bypass financial responsibilities.

Hora described how her husband remarried via an unregistered Islamic marriage, which allowed him to transfer money and assets to his new wife while pleading poverty in the family courts.

She said:

“My barrister said, ‘You’re not divorced from this lady yet, but you’ve remarried’.”

“He said, ‘Yes judge, in my religion I can have four wives’. And this is a High Court judge, and he said, ‘Yes, quite!’”

Hora felt that this comment suggested the judge supported her husband’s use of religious justification for remarriage before divorce, rather than recognising it as part of financial abuse.

Such judicial remarks betray a profound lack of understanding.

By accepting the “four wives” justification without interrogating the financial implication, that assets are being diverted to a new household to avoid a divorce settlement, the legal system becomes complicit in the impoverishment of the first wife.

Furthermore, women with an insecure immigration status face “immigration abuse”.

This is a potent form of economic abuse where an abuser uses the threat of deportation or immigration enforcement to trap women in financially dependent relationships.

If a woman’s right to remain in the UK is tied to her spouse, he holds absolute power over her existence.

Several women described struggling to open a bank account or obtain credit due to their migration status being exploited by their abusers.

Pakistan-born divorcee Fauzia had never had a national insurance number, child benefit or bank account until these were arranged for her by a social worker at the women’s refuge she turned to with her children.

Fauzia’s case illustrates total financial erasure; she did not exist on paper financially, making escape nearly impossible without third-party intervention.

Children Caught in the Crossfire

Perhaps the most harrowing aspect of economic abuse is the impact it has on children.

Almost 4 million children in the UK are suffering the impact of economic abuse in their families, with some having pocket or birthday money stolen by the perpetrators.

Data from the charity Surviving Economic Abuse (SEA) showed that over the past year, 27% of mothers with children under 18 had experienced behaviour considered to be economic abuse, where a current or former partner has controlled the family’s money.

The tactics are petty, cruel, and damaging.

The research found perpetrators used various means, including stopping mothers from accessing bank accounts and child benefits, and refusing to pay child maintenance.

As a result, some children are missing out on essentials, including clothes and food.

One in six women said a current or ex-partner had stolen money from their child, such as birthday or pocket money, and the same number said they had stopped or tried to stop them from accessing benefits they were entitled to.

The timing of this abuse is often calculated to inflict maximum distress.

One mother quoted by the charity, whose children are now adults, said:

“My ex would stop maintenance payments right before Christmas.”

SEA’s chief executive, Sam Smethers, noted the severity of this dynamic:

“Economic abuse is a dangerous form of coercive control and children are being harmed by it every day.”

“Our research shows that perpetrators are stealing children’s pocket money, stopping mums accessing child benefit, and refusing to pay child support.”

The government has acknowledged the scale of the issue, with Jess Phillips, the government’s minister for safeguarding and violence against women and girls, stating:

“Tackling economic abuse will be integral to achieving our goal of halving violence against women and girls in a decade, and we will continue to ensure children and young people are at the heart of this ambition.”

However, for the South Asian community, this ambition must translate into culturally competent action that recognises how children are used as pawns in transnational financial disputes.

The evidence is overwhelming: economic abuse is a systemic crisis that disproportionately shatters the lives of minority ethnic women in the UK.

It is a multifaceted issue involving cultural coercion, labour market exclusion, legal ignorance, and the weaponisation of immigration status.

The current systems, from the CMS to the family courts, are failing to look beyond the surface, allowing abusers to hide behind self-employment, overseas assets, and religious loopholes.

Addressing these inequalities requires policies that take women seriously, while also being culturally sensitive and aware of the multiple challenges these women face.

Until the government and legal bodies close the loopholes that allow abusers to manipulate systems to destroy lives, South Asian women and their children will continue to pay the price for a society that refuses to see the full extent of their financial captivity.