"It was a matter of great pride that the World Cup footballs were provided by a Pakistani company."

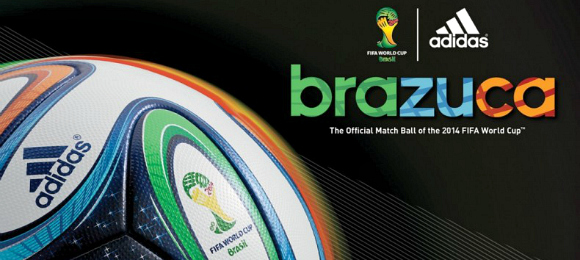

When the 2014 FIFA World Cup kicks off in São Paulo, Brazil on June 12 there is a very good chance that host nation Brazil and Croatia will be using a Brazuca ball made in Pakistan.

The nation, ranked 159th by ruling body FIFA, won’t be one of the thirty-two participating team’s at the most watched sporting event in the world. However its industry has joined forces with China as key suppliers of official Adidas AG (ADS) World Cup footballs.

Forward Sports factory in the eastern town of Sialkot, Pakistan have made the match balls. The plant stands in the mist of the hustle and bustle of the Grand Truck Road, the ancient highway that cuts across the subcontinent through to Kolkata.

Forward Sports has been working very closely with Adidas, and since 1995 have supplied officially recognised footballs for some high profile tournaments and competitions, including the Champions League, German Bundesliga and French League. Now the World Cup in Brazil will also see a Sialkot-made football passed around in its official line-up.

Khawaja Masood Akhtar, CEO of Forward Sports said: “It was when I felt the roar of the crowd at the 2006 World Cup that I dreamt of a goal of my own, to manufacture the ball for the biggest tournament on the planet.”

Such is the buzz in Pakistan that the Brazilian embassy in Islamabad had laid on a series of activities to celebrate the World Cup’s arrival. They had put on a football photo exhibition by Brazilian sports photojournalist, Jorge Rodrigues. The photos go back decades capturing players in action and crowd reactions.

In the factory, 90 per cent of those working on the new football were female. This is unusual for Pakistan, where women are largely expected to stay at home and look after the family. Akhtar admitted they were more diligent and meticulous than their male counterparts.

Mother of five Gulshan Bibi has no idea who Cristiano Ronaldo or Neymar are but she cannot wait for the World Cup, solely because she helped make the footballs and said:

“I’m really looking forward to the World Cup and inshallah (God willing) we will watch the matches. The balls we make will be used and all the women work here are very proud.”

Interestingly, the new ball to be used in Brazil offers a completely new spec to the one used in the 2010 World Cup that was held in South Africa. Named the ‘Jabulani football’, it caused much controversy due to its ‘erratic’ and ‘unpredictable flight’. Scientists admitted that the machine made Jabulani ‘too smooth and too perfectly spherical to fly straight’.

With this criticism in mind, Adidas went back to the drawing board and spent two and a half years creating a new, more suitable ball, which they named ‘Brazuca’ (slang for ‘Brazilian’).

Now built for purpose, the Brazuca sees a revolutionised design with six interlocking panels, all identical to each other. The ball, which is made of a synthetic material has also been ‘thermally bonded’, keeping out moisture.

The whole process from start to finish takes forty minutes. The production of the ball begins with a flat white propeller shaped piece of polyurethane. Brazuca’s distinctive bright colours and glue panels are added to the ball’s rubber bladder.

Next, the seams are treated with a sealant, after which the ball is heated and ‘compressed in a spherical clamp’, bonding the panels together to give its correct shape:

“We take unskilled workers and train them. This is a job that is not available anywhere else. You have to get someone with good attitude and train them” said Akhtar.

They are tested for roundness, durability and impact on numerous machines. Then and only then do they pass the test.

While this is a great moment of pride for ordinary workers of Pakistan, who will have little chance of experiencing the World Cup in person, there has been much controversy over the labour cost.

The retail price of the Brazuca amounts to $160 (£95), whereas the monthly wage of Gulshan and her colleagues is only $100 (£60). Sadly, it seems that even hugely successful competitions like the FIFA World Cup are not innocent to exploiting the cheap labour of developing countries.

However, for millions of football fans in Pakistan, India and the other South Asian countries, all eyes will be on the World Cup, and not solely on the players but on the Brazuca which they have so proudly made.