“A once thriving industry, destroyed by colonialism”

The sewing industry of Bangladesh is long rooted within the country’s history, pre-existing Bangladesh’s independence.

‘Made in Bangladesh’ is stitched onto countless garments all over the world. Yet, the history of the sewing industry remains forgotten.

Dhaka was a thriving, popular and successful region in Bengal; sewing and textiles were the talents of the land. Since the 1971 Liberation War, Dhaka is the capital of what is known as modern-day Bangladesh.

Bengal’s muslin cloths and cotton fabrics were made famous across the trading world, spanning centuries.

Dhaka had become the world’s hotspot for cotton muslin cloths. The material was dubbed the ‘Dhaka Muslin’ as a result of its reputation.

Taken from an extract from the book ‘Arthasastra’, by Kautilya also known as Chanakya, Ancient Indian teacher and philosopher of the Mauryan Empire said:

“Bengal was very famous for that weaving industry.”

The cotton plant Phutti Karpas used to form the muslin cloth, only grew in the Dhaka area. It was unique to the Bengal region and attempts at growing it outside failed.

Bengal prospered in their sewing industry for thousands of years, until colonisation led to its demise.

Sewing Industry in the Ancient Era

Renowned for their material, the rich cotton production beginning thousands of years ago. The textiles and sewing industry of Bengal was recorded to be popular before and throughout the Mughal Empire.

Throughout history, there are documents of Bengal’s textile trades. The Periplus of the Erythraen Sea recorded the trade between Bengal merchants.

It includes trade relations between Bengal, the Arabs, Greeks and Red Sea Port.

The Greeks referred to the Dhaka muslin cloth as ‘Gangetika’ and had access to Bengal ports thousands of years before Europe.

Evidence suggests it was the Romans who introduced Europe to muslin cloths. England had only come into contact with cotton weaving in the 17th century.

Shortly after, the establishment ended in the 18th century due to British Raj.

Sewing Industry during the 15th – 17th Centuries

During the famous Mughal rule of India, Bengal was known as the ‘Bengal Subah’. It quickly became the wealthiest region, producing 80% of silks which were imported from the entire Asian continent.

Bengal maintained its stance as the core and foundation for muslin trade worldwide, along with pearls and silk.

The muslin cloths were worn by royalty, within the Indian subcontinent and beyond. Through Arabian trades, Bengal textiles were famous in the Muslim world too.

Robes were created with the material and become a symbol of wealth and elegance and only in Bengal it was possible to create such fine cloth.

The region was trading within and throughout Asia itself. Markets were set up, selling the fine Dhaka muslin and more; popularity was rising rapidly.

Bengal weavers and tailors were highly talented, more so than their European counterparts. Eventually, Bengal’s trading expanded all over Europe and beyond.

Bengal’s woven textile was much admired across the world.

By the 17th century, the Dutch, French and British had opened textile factories in Bengal.

The ancient sewing industry of Bengal was split into groups.

In West Bengal, there were weavers known as ‘Ashwina’ who were the original weavers.

East Bengal, known as present-day Bangladesh, is where Dhaka was and is still located. They were known as the ‘Balarami’ weavers meaning the best.

Alongside these groups, there were several other sectors and classes of weaver’s all with different roles and talents.

The sewing industry created its materials and wove eccentric patterns.

During the 15th century, corsets known as ‘Kanchulis’, were embroidered. By the 16th century, a variety of designs and patterns were introduced.

The 16th century saw lengthened sarees produced with different textures and varieties like; ‘gangajolis, mokhmols and chelis’.

By the time it was the 17th century, an assortment of colours was added to the garments. The Bengal sewing industry was progressing rapidly.

The garments created in Bengal quickly became staples of fashion, across the world.

However, by the 18th century, the once-popular sewing industry of Bengal began to decline.

British Raj and the East India Company

The British East India company had initially settled in the Indian subcontinent in 1600. Slowly, it began taking control of trading over the following centuries.

Battle of Plassey, 1757, saw the British East India company take over Bengal completely. After this defeat, Kolkata was made the capital.

Arguably, this was the beginning of British colonialism and imperialism which affected all aspects of life, particularly the sewing industry.

The spelling of Kolkata to ‘Calcutta’ for a brief time is a symbol of forced, colonist change.

By 1858, the British took full control over India, this period is known as the British Raj.

The British wanted to sell their own cotton goods, and they destroyed the local industry.

The British Raj led to the decline of Bengal’s prosperous sewing industry. They began restricting Bengali imports to Britain through protectionist policies.

Previously, in 1700 an act was passed which illegalised import of cotton from Bengal, China and Persia as the popularity and introduction of cotton threatened Britain’s woollen industry.

Britain imposed penalties throughout the 18th century to ensure commoners were not indulging on the cotton made muslin cloths from abroad.

The inception of British Raj included colonial policies which caused Bengal to struggle heavily.

The British forcefully increased heavy duty and tariff prices, which impacted the trades. Britain was working to sell their own cotton goods while destroying Bengal’s sewing industry.

Bengal was imposed a heavy duty fine, it had increased to 75% for imports.

By restricting Bengal from importing and exporting their textiles, Britain made room for their own success at the expense of Bengal’s downfall.

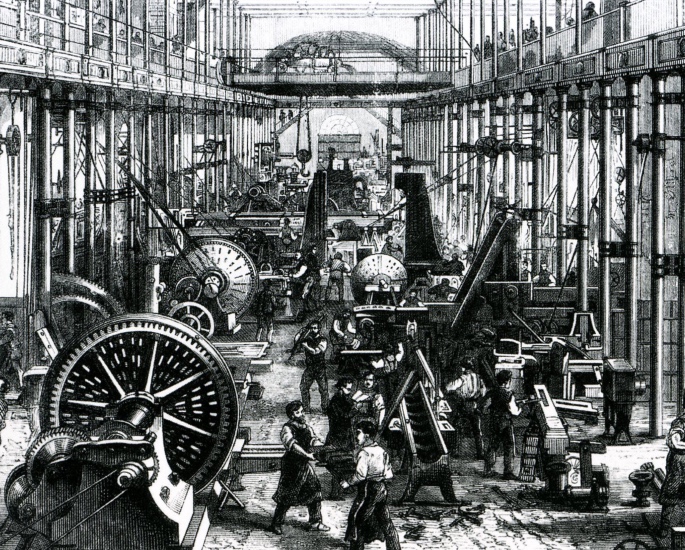

Britain was fruitful in producing their own quality of cotton by this time in history.

This was due to the British Industrialisation which saw Britain developing in manufactory and labour.

While Britain’s industrialisation improved the British economy, the British Raj caused deindustrialisation in Bengal.

Work conditions for Bengali weavers became harsh under British rule, they were forced into workshops called ‘Kothis’.

Within these ‘Kothis’, workers were enforced to labour in punitive conditions, like bonded slaves.

Inevitably, the British Raj caused the fall of the once-booming sewing industry of Bengal and the Dhaka muslin cloth’s pride vanished with its weavers.

Sewing Industry Today

Bangladesh is a third world country and its once reputable status as weavers and tailors, is lost. The forced deindustrialisation of Bengal’s cloth and sewing industry by British colonisation are remnants of the past.

Yet, Bangladesh still remains one of the world’s leads to garment production. Bangladesh’s sewing industry includes 4,825 garment factories, where workers are exploited daily.

There are around 3.5 million garment workers in Bangladesh who supply mainly to Europe and North America.

Brands like Primark and New Look, are amongst several high street brands which manufacture their garments in Bangladesh.

Fast fashion has made the pay gap between manufacturing and retail prices increase.

It is a form of cheap labour by these wealthy brands; displayed through the gap between manufacturing and retail prices.

Brands pay approximately the equivalent of $5 (£3.74) for the manufacture of a t-shirt, which they retail for $25 or higher (£18.71) in stores.

The $20 (£14.97) difference is not just profit for the brand, it is the exploitation of the workers.

Media personality, Kylie Jenner caused controversy after it was revealed she had not paid Bangladeshi workers, despite her net worth being a staggering $7 million (£5,238,765.00) and her business valued at $1 billion (£748,395,000.00).

Like Jenner, there are many more who misuse the disadvantages of garment workers in third world countries.

Bangladesh’s government policies do not protect workers’ rights for minimum wage, often brands vary in wages given. This enables and allows global brands to abuse Bangladesh’s sewing industry.

During the times of the Bengal Subah, workers had the highest living standards and wages in the world. They were earning 12% of the World’s GDP.

This has changed drastically as workers have a low living standard. They barely making a livelihood despite the rigorous hours they work in dangerous conditions.

The workplaces often do not have any health and safety regulations, leading to injuries and deaths.

Since 1990, more than 400 factory workers have died, and countless others have been injured.

85% of the sewing industry is made up of women, hailing from impoverished backgrounds.

Yet, they are heavily discriminated against. Workers have been refused the right to maternity leave by their employers putting mothers and their children at risk.

This is a very acute example of modern-day slavery and one which should be acknowledged as such.

The Rana Plaza factory has been described as encouraging forced labour and slavery.

The rife conditions of Rana Plaza were ignored. Eventually, in 2013, the factory collapsed, killing 1134 workers after the death search ended from 24th April – 13th May.

This incident is considered to be the worst and deadliest garment related disaster to have occurred in history.

Despite years of exploitation and unfair working conditions, the loss of life at Rana Plaza finally removed the façade that cheap clothes for fast fashion are the result of the price tag on human life.

Rana plaza is one of many examples of tragedies which occur throughout the sewing industry of Bangladesh.

Foundations such as the National Garment Workers Federation (NGWF), have been demanding for the rights of garment workers in Bangladesh since 1984.

NGWF provide legal education and support to workers while promoting their rights and demanding stronger legislations.

From a popular and prosperous establishment to a poverty-stricken, exploited workforce, the sewing industry of Bangladesh is a prime example of the aftermath of colonialist imperialism.

The Bengal talents are still needed in the fashion world as they were in history, but without the cost or credit rightfully awarded.

A lot of the garments we own are woven tirelessly by Bangladeshi tailors.

They work in unhygienic, dangerous conditions to make a livelihood and remain captive to their poverty and despair, despite their exploitation and hard work.

Without the sewing industry of Bangladesh, fashion retail would struggle. Yet, it is the Bangladeshi workers who struggle every day to provide garments to industries and brands we buy from.

You can support Bangladesh’s sewing industry and garment workers, including their families.

Better their work conditions and bring change by donating to the links below:

- Unison Appeal x Labour Behind the Label

- Childhope – Protect and support the children of Garment workers

- Support underprivileged garment workers all over the world

The coronavirus pandemic has heavily affected the sewing industry of Bangladesh. Giant fashion brands refusing to pay wages has caused further distress, worsening livelihood.

Below are relief funds to help workers during the pandemic: