"There's been casual racism within cricket"

Racism across women’s cricket has often become a dark shadow from the men’s game.

Similar to their male counterparts, female cricketers of colour have also experienced racism, confronting a traditionally white space.

The key difference is that historically racism within women’s cricket was not talked about much or reported in comparison to the men’s game.

Academics and authors have gone on to dig some of it through research, oral history, and interviews.

Thereafter, in the 20th-century female cricketers of colour from India, Australia, and England have also opened up about racism inside and outside the sport.

We explore racism within women’s cricket through research, along with recollections and experiences of former cricketers.

Excavating from a Historical Perspective

Research indicates racism in women’s cricket was historically put to the side-line, with most simply snubbing it.

One of the major reasons for this was the focus on the “whiteness” and “maleness” in respect to the analysis of cricket racism.

Nevertheless, there are some examples and accounts which indicate the ignorance and cricket racism within women’s cricket.

Raffaelle Nicholson explores some of this in her critical essay: Confronting the ‘Whiteness’ of Women’s Cricket: Excavating Hidden Truths and Knowledge to Make Sense of Non-White Women’s Experiences of Cricket (2017).

She argues that even with the decolonisation process being complete, an exclusion process took place within women’s cricket on the basis of ‘racial difference.”

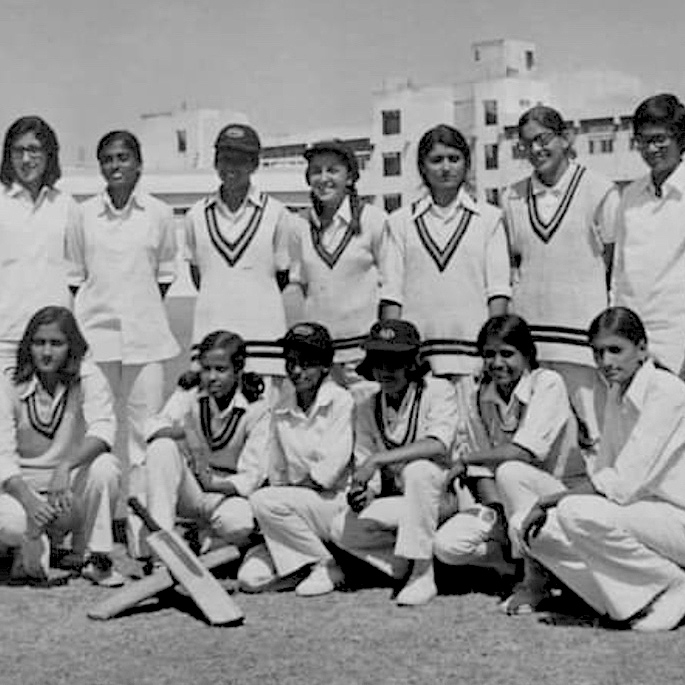

Rafaelle specifically cites the example of the Indian women’s team not receiving an invitation to play in the 1973 Cricket World Cup.

She has a point, especially with Indian women playing a lot of cricket between 1970 and 1973.

That same year the first Women’s Inter-State Nationals had taken place in Pune during April.

She also felt the evidence was suggesting that the Women’s Cricket Association began distinguishing between the old colonial mentality of “them’ versus ‘” us”.

This saw the marginalisation of African Caribbean and South Asian women based on class in comparison to their white counterparts.

WCA’s racial superiority stance was quite evident when the Women’s Cricket Association of India went on their first England tour in 1986.

Tensions began mounting between the two nations during the 1st Test of that tour.

In one episode, Indian skipper Shubhangi Kulkarni went on to verbally accuse English umpires as well as accusing them of cheating.

The WCA thought that the Indians were not playing in the spirit of the game, especially being nit-picky with the sightscreen amongst other things.

Newspapers began reporting that post-match the WCA Chairman had gone on to threaten India with exclusion from women’s cricket.

Several of the Indian cricketers became emotional, with Kulkarni leveling “racial abuse” accusations against the Chairman.

Whilst the visitors did receive an apology in writing after expressing to leave the tour mid-way, the official WCA account was somewhat different:

“One WCA official told the Daily Mail that the heart of the problem was that ‘the Indians are a race who will always find something to complain about’ (Daily Mail, 5 July 1986).”

Even if the WCA thought the Indians were lacking in sportsmanship, privately informing them of possible ostracisation was a step too far.

Another marker was what Rafaelle describes as “racial otherness.” English female cricketers had traditionally worn skirts to symbolise their feminity until the ’90s.

This was a deliberate form of opposition to Indian and West Indian women players wearing trousers.

Heyhoe-Flint, R. and Rheinberg, N. (1976) in Fair Play: the story of women’s cricket presents a prime example of such conformity.

They cite how West Indian women had no choice but to play a 1973 International XI World Cup game in white shorts “to conform with the other [white] members of the team.”

Many will believe this marker of difference was a form of racism within women’s cricket.

In an interview with Rafaelle, a former player and WCA Chairman argued two points. This was in respect to women’s cricket being predominant white until the 90s.

Firstly women’s cricket had inherited a dominant white space from the men’s game.

Secondly, the onus was on African Caribbean and South Asian girls and women to “knock on the door” as opposed to the key decision-makers selecting players from various backgrounds.

Mike Marqusee alludes to this blatant issue in his book, Anyone But England: An Outsider Looks at English Cricket (1994).

He said with the English authorities not acknowledging racism in the men’s game, created a “culture of complacency and denial”, which very likely spread into women’s cricket.

Contemporary Incidents

Despite earlier racism being ignorant of women’s cricket, some post-millennium incidents came out in the open.

Though nothing substantial came to light amidst Azeem Rafiq opening a big pandora box into the men’s game.

The modem era was a mixed form of direct and indirect racism, along with discrimination. Racism became evident both on and off the pitch from a team context and individually

Former Indian cricketer, Jaya Sharma spoke about how the women’s cricket team of India was subject to racism. This was during a Facebook LIVE session in spring 2020.

She reveals the organisers of the 2005 Women’s Cricket Cup in South Africa had gone on to treat the Indian team differently.

As per her say, India was the second team to arrive for the mega event, However, despite their early arrival they had to stay in undesirable conditions, with no fan interaction.

She particularly was stressing on the fact that special provisions were made for “white” teams. Sharma recollected saying:

“We were the second team to arrive at the venue and they (the organisers) had arranged for us to stay at these one-story, two-storied buildings, 7-8 of them.

“They welcomed us and they said that we can move into our building. We went to see the buildings that we had been allotted. To our surprise, our building, which was the sixth or seventh building, had no fans or ACs.”

“As a team, we were shaken. How can they not even provide fans?

“Our manager went and spoke to the organisers but he was told that the first 3-4 buildings were already reserved for the white teams. And those buildings had ACs, had everything basically.”

In the video, she goes on to talk about how the team took inspiration from this incident to gel together. It was only after the team progressed to the final that they had a more privileged status, moving into the “first building.”

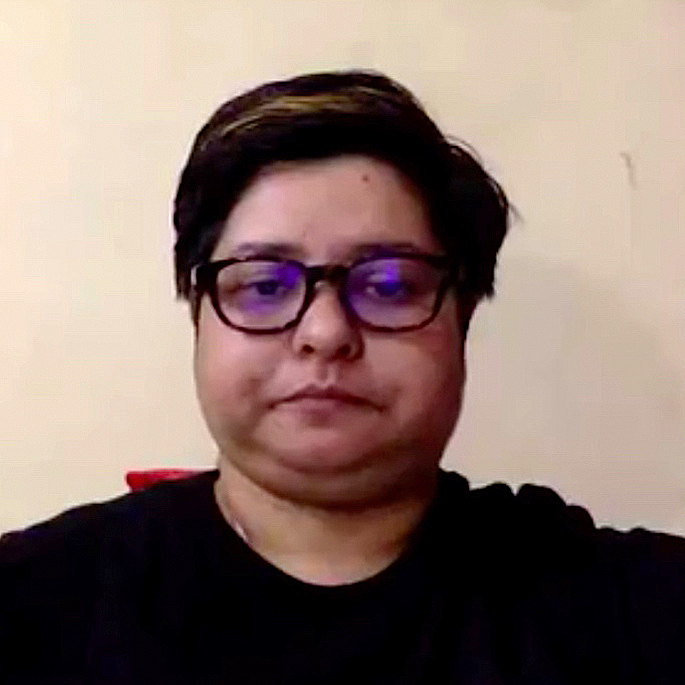

Former Australian allrounder Lisa Sthalekar of Indian origin is one of the bravest cricketers. She had shed some light on her racism story in 2020.

In an exclusive conversation with cricbuzz, Lisa went on to share her experiences of facing “casual racism”, whilst representing The Southern Stars. She said:

“There was one time where… I don’t even know the circumstances, but my teammates were trying to pin me down and put a bindi (worn in the middle of the forehead by Indian women) on my forehead with a permanent marker (because I was Indian).

“And I was fighting that off because it pissed me off. There’s been casual racism within cricket teams regularly growing up.

“People would say, ‘You need to carry the bags, Lisa’… things like that over the years.”

“Obviously, things changed in the environment and what was acceptable changed, but I’ve had a few incidents that haven’t been great.”

Even though it was not pleasant, Lisa added that she learned to handle these situations, with maturity:

“But I think if you’re a sportsperson you tend to have a thicker skin because you’re constantly getting judged or critiqued or the banter on the field. Maybe that allowed me to cop.”

Though, does that necessarily apply to all? Not everyone is as strong in reality. She did not bother too much about comments such as “carry the bags, Lisa.”

Instead, Lisa was focusing more on fitting into a particular group. She cited an example of playing along with the same mindset:

“No, I’d tell them to f*** off basically. It was a bit of a joke… To be honest, some of the times to cope with it, I said it as well.

“You try and get in with a joke before the joke is made out of you, so to speak.”

She also told how her sister had undergone severe racism and first encountering it at school. Hence, racism was not just a cricket issue but a much deep menace in society.

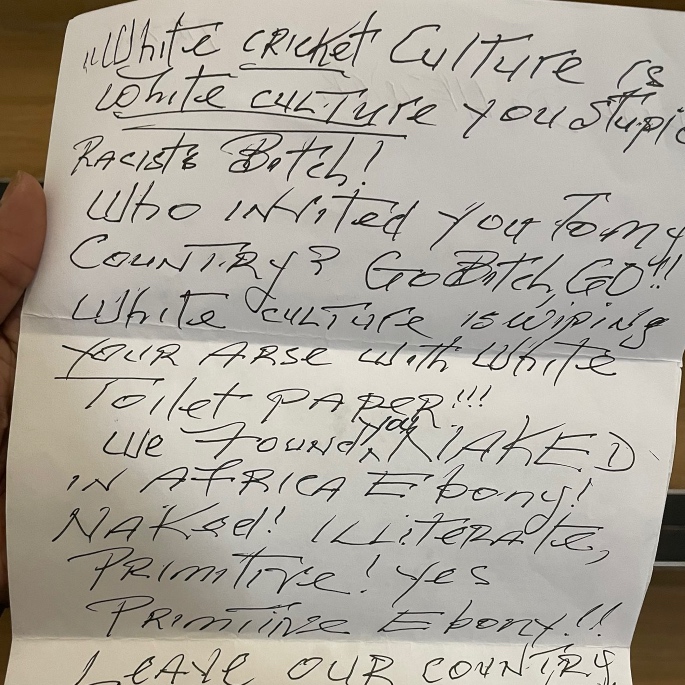

In a separate incident, former England cricketer and commentator Ebony Rainford-Brent had to face racial abuse.

On November 17, 2021, Ebony went on Twitter to share a horrific racist letter, tweeting:

“Interesting…Thinking face Born in South London but apparently I was found naked in Africa as a primitive Face with tears of joy Had some letters in my time but this one up there!”

The letter with someone’s handwriting was promoting racist terminologies. This included “white culture is white culture”. The letter was also directing Ebony to “leave” what the writer describes as “our country.”

This was like a blast from the past, with the “us” versus “them” theory reappearing. Some of the harshest words used in the letter included:

“We found you NAKED in Africa Ebony! NAKED, illiterate, primitive! Yes primitive Ebony!!”

Following the letter’s revelation, Ebony had a lot of support from the wider cricket fraternity. Former West Indian great Michael Holding was a big pillar of support.

The letter also reinforced the whole idea of institutionalised racism and the importance of educating people.

The traditional lack of diversity has had an impact on the game. Only a few players from ethnic minorities have played for England, which included Isa Guha.

Though, there are encouraging signs. Sophia Dunkley made history by becoming the first black woman to represent England in Test cricket.

Also, Scottish cricketer, Abtaha Maqsood has become a pioneer for the Midlands region. She had a good outing with Birmingham Phoenix in the inaugural Hundred season.

Efforts are ongoing to eradicate racism and promote diversity in women’s cricket. However, there is a long way to go.

After all, a stronger representation from people of colour will only enhance women’s cricket further.

Meanwhile, if any woman has experienced or faced cricket-related racism, they must not suffer in silence. An individual should report any discrimination to the relevant authorities.