"Bollywood has always opened doors across the world"

Sunny Singh, a writer, novelist, public intellectual, and an unyielding champion for inclusion, has embarked on a remarkable journey that spans generations.

Her notable works include the acclaimed novel Hotel Arcadia and a study of Amitabh Bachchan for the BFI’s film star series.

In 2016, she launched the renowned Jhalak Prize, celebrating literature by writers of colour.

She is also a co-founder of the Jhalak Foundation, dedicated to various literary, artistic, and literacy initiatives in the UK and beyond.

Born in Varanasi, India, Sunny was raised in a country of ardent film fanatics.

Her early years were spent swaying to the tunes on the radio and donning attire inspired by the glamorous world of Bollywood.

Yet, for Sunny, Bollywood represents more than just a form of entertainment.

It’s a cultural force that not only entertains but educates, influences moral compasses, and serves as a mirror reflecting the collective consciousness of a nation.

In an exclusive interview with DESIblitz, Sunny Singh takes us on a mesmerising journey through her latest literary offering, A Bollywood State of Mind.

This riveting work traverses time, geography, and the intricate tapestry of modern Indian history and cinema.

Through her words, we delve deep into the heart of Bollywood and explore its profound impact on our lives, society, and the world.

As we chat with this distinguished author, we find ourselves in the presence of someone who articulates Bollywood’s significance in an increasingly interconnected world.

Sunny Singh’s insights promise to reveal the threads that connect us all to its captivating allure.

What inspired you to delve into Bollywood’s impact in the book?

It feels like I have been writing or at least trying to write this book all my life.

Commercial Hindi cinema – often now better known as Bollywood – was my first exposure not only to films but also to storytelling conventions, music and aesthetics.

It laid for my interests in popular and classical music and dance, in literature and philosophy and not only in India but also elsewhere.

Over the years, I realised that I am not alone in this.

For many millions of us, and across the globe, not only in India, this cinema has been the stepping stone to a world of narrative, culture and aesthetics.

I wanted to write a book that would record and narrate this phenomenon.

And, I wanted to reach out and connect with the many fans of this brilliant cinema (and hopefully create more fans).

Can you share key Bollywood moments that have shaped Indian society?

There are so so many! My book covers a span of over a century of cinema and in that period, films have played a part in not only reflecting but also shaping our society.

If I had to pick just two, I would pick the ways films in pre-independence India were a space and form of resistance.

One of my favourite stories is from 1930 when the colonial administration banned the Tamil film Thyagabhoomi, and that too after months of huge success.

Except as the word spread, people surrounded the iconic Gaiety theatre – which has sadly shut down now.

The people formed cordons against the police while the film was screened continuously inside.

“By the time the police seized the print, the message of the film had spread far and wide.”

The second incident may seem quite frivolous.

But it’s Sadhanaa’s reinvention of the churidar-kameez, created for her by Bhanu Athaiya who later won an Oscar for Costume Design for Waqt.

The fact that a star or film could break down entrenched ways of dressing across society is as extraordinary as realising that there was a time and place when clothes were so sharply divided on religious lines.

Were there any surprising encounters during your research?

Again, there are so many brilliant moments, and I was really sad that I could not include all of them in my book.

Specifically, I am endlessly fascinated by the complex ways the films and the industry’s people have participated in various aspects of Indian history and society.

So, for example, there were state-backed promotional trips made by Raj Kapoor and Nargis in the 50s to Moscow.

That was an early use of cinema for the exercise of soft power by India.

For me, a really fascinating instance was how filmmakers sought endorsements by leaders of the freedom movement, including Gandhi, in the run-up to independence for their films.

Sadly, there is no evidence that any leader agreed to give such endorsements.

But it didn’t stop filmmakers from using images, words and references to freedom fighters in their films and even on posters.

In some cases, this filmic defiance extended to including documentary footage in films which in turn would lead to trouble with colonial censors.

How do you see Bollywood contributing to the landscape of India?

In many ways, popular cinema is a space of discussion and debate in a democratic society.

We only need to look at a film like Lagaan that explicitly addresses anti-colonial dissent in a super entertaining way.

Even right now, Jawan is explicitly engaged with issues that matter to most of the country.

It does so in a metaphorical, entertaining way and there is a large element of wish-fulfilment which is logical as it’s an entertainer, not a documentary.

Significant portions of popular cinema have been deeply critical of the Indian state, society and culture since its inception.

In turn, their ability to present ideas and issues in entertaining ways and to large parts of the population has impacted how these were seen.

This relationship is not causal, direct or explicit because that is not how popular cultural production works.

Yet popular cinema – whether Bollywood or many others across the country – have always been crucial to the social and cultural landscape of India.

At the same time, the politics of films and their makers is neither necessarily explicit nor even predictable.

For example, Guru Dutt – often remembered as progressive – made and released Mr. and Mrs. 55 in the very year that Hindu women were granted the right to divorce.

“Divorce was a hugely contentious social, political and yes, religious issue at the time.”

The film is deeply regressive and patriarchal and Dutt falls clearly on the wrong side of history on it.

Even earlier, there were films denouncing caste discrimination, forced marriages or advocating for other causes.

Even in 2023, it’s telling that some of the biggest hits of the year so far address political issues.

How has Bollywood connected with global audiences?

In my travels, I realised that this cinema reaches far across the globe.

Then my research made me realise that it was a global, cosmopolitan industry from its early days.

Even in the earliest days, Indian filmmakers were shooting their films in Europe, even casting European actors.

This was easier for silent cinema of course as language was not an issue.

But even in the early days of sound, Bombay filmmakers weren’t bound to post-1947 or even the region.

After all, the first Persian language sound film was made not in Iran but in Bombay!

For me, Bollywood has always opened doors across the world.

I have been given access to homes, institutions, and even sacred sites. Not because people knew me but because they knew my movies.

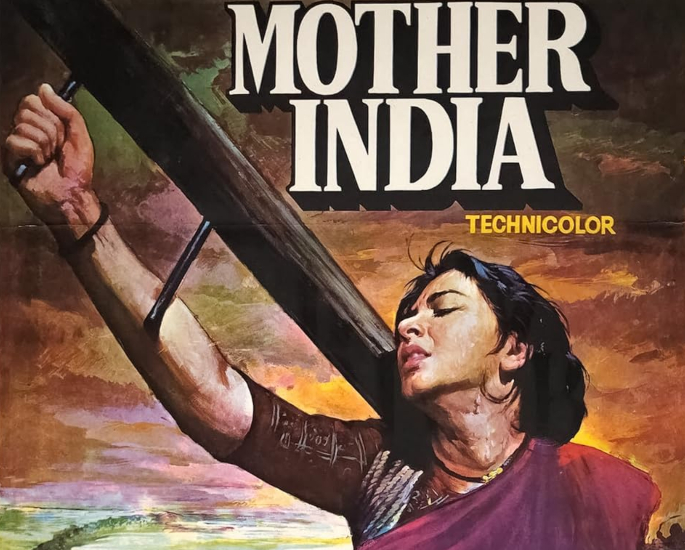

There are so many anecdotes to share but one day I want to write a book on the travels of Mother India.

It speaks to SO many women in so many parts of the world.

I’ve met women in remote hinterlands of multiple continents who have not only watched the film but have clear, powerful memories of it.

One of my favourite moments was meeting the grandmother of a Greek friend.

She loved not only Mother India – which had been a huge hit in Greece in her youth – but knew lots of classics.

I then learned that many songs from our 50s movies had been translated into Greek and recorded by Greek singers using different instruments.

She knew many of these songs although not in Hindi.

Much to the bemusement of my friend, we sat on her porch singing all the songs we both loved, but in two very different languages.

Can you tell us about the most personal moment you had while writing this book?

This cinema has been a part of my life in so many big and small ways.

My first fashion moment is a kindergarten class photo where I am dressed in a psychedelic print kurta like the ones worn by Zeenat Aman in Hare Rama Hare Krishna.

And then as I got older, there were Sridevi’s chiffon saris. And Bachchan’s 70s jackets with the stripe down the sleeves and on the back.

I forget how many versions of that I have worn to tatters!

“I think it was the pandemic that brought home the value of this cinema.”

My family is spread across the world, and we went almost three years without seeing each other.

I made separate playlists with songs that each member of my family loves and those became a way to keep me company as I missed them.

And then when we all finally got together, we talked and ate and laughed.

After the first few days, we stayed at the dinner table and had a joyful, loud, boisterous song session, using the table as a tabla.

It was a reminder of how much pop culture binds us.

And in India, that pop culture is likely to be cinema – and not only Bollywood – in its many forms.

How does your advocacy work tie into the themes in your book?

I am both an academic and a novelist.

So, I suppose it is predictable that I am fascinated by the stories that we tell, why we tell them and most importantly, how those stories impact and even shape our worlds.

I think we have enough evidence that stories we tell of ourselves, or others can help shape opinions not just of individuals but vast collectives.

Stories can make someone seem like a friend or turn them into an enemy. They can make us love or hate people.

And for over a hundred years, cinema has been the largest and most influential form of storytelling. And some of those have been harmful.

But I think the majority of Indian cinema has tried to imagine and narrate a free, democratic, equitable society, even if not in explicit or straightforward ways.

It is also one of the earliest, largest, and influential cinemas across the world that is also historically – and explicitly – anti-colonial.

These ideas are of interest to me in my fiction, my research as an academic, and of course as an advocate for equality.

I frequently turn to Bollywood for both inspiration and warning because it has produced models of stories that create positive change as well as stories that can harm.

How do you see the role of literature in promoting diversity?

As I said earlier, literature and arts teach us to imagine who we are as individuals and collectives.

They not only impact how we dress, how we decorate our homes and things that we value, but also how we see the world around us and our place in that world.

We need only look at British literature of the colonial period (and even after) to see how colonised peoples, lands and cultures were represented.

“That representation helped justify not only the oppression but also immense violence.”

On the other side, there were stories of the colonised peoples which inspired and created resistance, and defiance.

Who we represent in our stories and how we represent them and ourselves is crucial to building a society. For good and for bad.

A greater range of storytellers – as musicians, artists, filmmakers, writers, and actors – means a society is able to imagine difference not as a threat but as something beautiful and of value.

By nurturing the widest range of stories and storytellers possible, we not only create great art but also an inclusive, equitable society.

Has the Jhalak Prize impacted your view on representation?

The Jhalak Prize was started with the same principles I mentioned earlier.

We need to hear and know each other’s stories if we are to live peacefully with each other.

And that applies to every part of the world.

Establishing and administering the prize has made this clearer to me.

When we have a vast range of voices, when more voices feel safe and empowered to speak, everyone benefits.

How has your background informed your approach to writing?

Growing up, I was fortunate to be exposed to great literature in Hindi and English from across the world.

But quite early on, I realised that I loved the stories told by filmmakers like Gulzar, Manmohan Desai, and Nasir Hussain.

I spent many years figuring out how they made compelling, memorable, entertaining films.

“When I started writing, popular Indian cinema was an important influence and inspiration.”

In A Bollywood State of Mind, I got a chance to bring those same skills to telling the story of the cinema I have loved for most of my life.

I often write to Desai films playing in the background as a reminder to create something that can be complex and packed full of information and ideas but also, well paced and entertaining.

I hope the book works like a great masala movie!

How do you think Bollywood continues to evolve?

My book covers over a century of Indian and film history and teases out the changes in society, economics, politics and the way our films reflect, represent and even lead these.

At the same time, my book looks at the changes in film technology and techniques and how Indian cinema as a whole adapts.

Indian films have been very quick to adapt new technology – sound, colour, the switch to digital – although often this has been inhibited by resources.

However, the ways in which Indian cinema uses new technology are entirely different and unique.

So, for example, Indian films adopt sound – talkies – faster than most film industries in Europe or Japan.

In fact, the only other industry that takes to talkies with the same enthusiasm is Hollywood.

But the way the two industries use that technology is very different.

Part of this difference has to do with cultural values, social and political conditions, and of course economics.

My book tracks these changes in society, technology, culture and cinema in India but weaves them together in a single brightly coloured strand.

In your opinion, what is the enduring appeal of Bollywood?

This is a huge question, and I would be very wary of generalising.

Different countries and cultures respond to Bollywood and other Indian cinemas in different ways.

However, part of the answer is that it is a different kind of cinema.

“It’s a different kind of storytelling that revolves around different kinds of characters.”

Many years ago, one of my cousins was watching one of the Terminator films on TV.

And at one point he turned to me and said, ‘he doesn’t have anybody so for whom does he want to save the world?’

I didn’t have an answer then, but the question got me thinking and researching.

A Bollywood State of Mind answers the question you have asked and the question my young cousin asked.

This cinema matters to billions across the world because it’s about family, community, and collectives.

It’s about those of us who have not been – and are still not – fully represented in or by Hollywood or other cinemas produced by the former imperial powers.

It’s for and about us!

In this captivating conversation with Sunny Singh, we are left with a renewed appreciation for the magic that is Bollywood.

A Bollywood State of Mind is not just a literary masterpiece but a testament to the enduring influence of Indian cinema on global culture.

It’s a love letter to the vibrant, larger-than-life world of Bollywood, and a reminder that, no matter where we are on this planet, the silver screen has the power to bind us all.

Sunny Singh’s journey, from her childhood days of watching films with friends in India to her current role as a professor and advocate in London, showcases the far-reaching impact of Bollywood.

We are reminded that Bollywood is not just an industry; it’s a way of life, a source of inspiration, and a shared cultural heritage for millions.

Sunny Singh’s insights and her remarkable book emphasise the ability of cinema to shape our perceptions and the indomitable spirit of Indian cinema that continues to capture hearts around the world.

Grab your copy of the book here.