“People carried the traumas with them across time and across continents”

Postcolonial literature has always been a useful tool for Eastern intellects to understand the aftermath of imperial rule and Empire.

It is not uncommon to come across novels and short stories that speak of displacement, loss and the struggle of resettlement. We will regularly read of the emotional battles that emerge from a confused understanding of where it is that we actually belong.

This fear of the unknown, or the ‘Other’ continues to be a prominent feature in this kind of literature. Whether derived from race, religion, or politics, for the most part, there is more that divides us than unites us.

For India and Pakistan in a post-partition era, the ‘Other’ manifests itself further via a physically carved out border. The last seven decades have been rife with political upsets.

Neither nation feels safe or secure with the other looming so near, and while attempts have been made to overcome barriers, this has been consistently thwarted by governments and authorities.

Sadly, in this current climate, we are also faced with hurdles when it comes to discourse. And sometimes opportunities to engage with each other and share ideas can be faced with censure.

There’s much to be said then, of authors from either side of the border who can come and sit together and discuss the commonalities that exist between them.

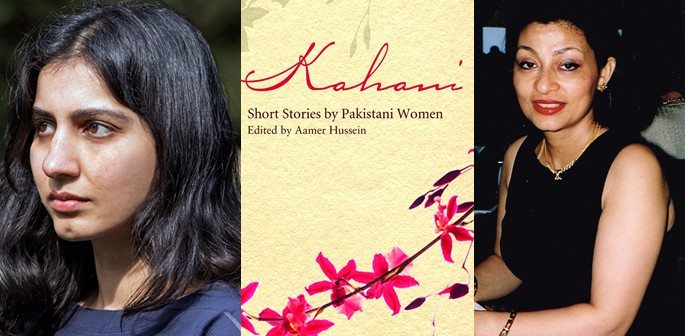

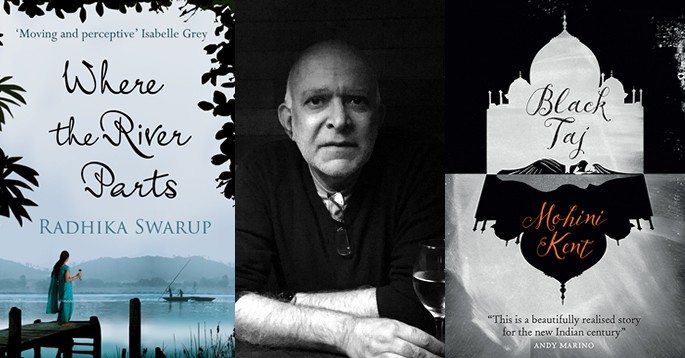

As part of the Asia House Bagri Foundation Literature Festival, three prominent writers of postcolonial literature, Aamer Hussein (Short Stories by Pakistani Women), Mohini Kent (Black Taj) and Radhika Swarup (Where The River Parts) address the resonating effects of partition that can be felt even today.

Chaired by editor and author Kavita A. Jindal, the question on everyone’s lips – has nothing changed 70 years later?

A Modern-Day Partition

Mohini Kent, author of Black Taj, who arrived in the UK at the age of 21 believes that partition never ended. India still exists in a partitioned state. Whether this is via class, caste or religion: “People carried the traumas with them across time and across continents,” she says.

Similar sentiments are to be found in Radhika Swarup’s novel, Where The River Parts, which explores pre-partition and post-partition as experienced by her female protagonist, Asha.

Despite having witnessed close-hand violence between Hindus and Muslims, Asha feels no enmity for Pakistan. However, her daughter Priya, who has grown up listening to the stories of the vicious ‘other’, does and with a ferocity that is almost alarming.

For South Asians, it is difficult to speak of Partition without some bias, depending on our background, culture and faith.

Even today, it is near impossible to find one complete history of Partition – we are faced with so many accounts of what happened – depending on which political party your family affiliated with or on whichever side of the border you sat.

Even in this setting with well-read authors, some particulars of Partition history are still debated amongst the room – was Muhammad Ali Jinnah for an Islamic Republic or a secular state? Should independent India become a religious state?

Despite the passing of 70 years, new generations are still inherently, almost subconsciously, connected with their past. Even if they live and work outside of South Asia like our panel of authors.

The Issue with Empire

Of the bitterness that still exists over Partition, both sides will, at least, agree on its source – the British Raj. As Mohini explains: “[The British] left behind fragmented lands that have still not gone away.”

Each of the different texts by Radhika, Mohini and Aamer explore the idea of a sudden shift in thinking, that was brought on by Britain’s changed policy to bring Independence forward. What resulted was complete chaos and confusion which led to distrust and violence:

Radhika Swarup puts this into context:

“When Brexit happens in 2019 people will have had many years to get used to the idea. In 1947, people had two days.”

Many found themselves harbouring dual identities – one which yearned for the idea of separate states, and one that wished to remain united with neighbours and friends.

Aamer Hussein’s anthology of Short Stories written by Pakistani Women also explores how fear leads an individual to hide behind multiple identities. In Farkhanda Lodi’s ‘Parbati’, Parveen leads a double life and is continually haunted by society’s judgement of her allegiance and her honour.

Much of the literature on Empire and Partition that we will come across today mentions this sudden spread of fear among communities. Interestingly, this also affects interfaith relationships as can be seen in Black Taj and Where The River Parts. Love is constantly thwarted and couples are separated. First, by religion and second, by nationality, and sadly this has even rippled down to present day.

A Different Time, A Different Generation

Another theme that runs throughout these books is the incredible resilience of the Partition generation. Despite facing such trauma and hardship, they continue to rebuild and resettle in lands that are not their own. In essence, they get on with their lives in the best way they can.

Many question why there is a general trend among older generations to remain silent on the horrors of partition. Parallels can be drawn to soldiers in war, who struggled with PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder). It seems that the grief resonates still among them – memories of a happy and content life that existed pre-partition have faded away.

What does remain however is a continued hostility between Indians and Pakistanis on a governmental level. As Kavita A. Jindal notes:

“It is a messy history, and we are living under the consequences. Even though Partition took place 70 years ago, it is still very raw and emotional. We can’t get beyond it because our countries can’t get beyond it.”

Interestingly, this in spite of the loss and trauma being predominantly localised – the majority of this “disease” spread in Punjab, but the rest of India remained largely neutral.

The panel unanimously agrees that forgiveness is the way forward. Elders need to learn to stop proportioning blame. Only then can tolerance and unification can take place.

Interestingly, this is where writers can step in. Tolerance can be brought about through literature, we can focus on similarities as opposed to differences. A broadening of education is also proposed – to invite multiple histories and perspectives to be understood by all communities.

The Dream of a Unified India

All the authors share a similar dream – a unified Indian subcontinent – one that does not exist on predetermined borders.

But, as one audience member asks, is this the general mood of popular culture? Is this what younger generations want? Are intellectuals prophesying something that is not desired by the masses?

Aamer steps in: “Young people now want to be able to cross borders and collaborate – they want to sing, dance, act, play sport.”

Mohini makes an interesting point: “If we talk about reunification, the only hope is Bollywood. Both governments should give them a mandate!”

But both Pakistani and Indian actors are forced to censor themselves in public. Despite the lengths made to encourage collaborations, this has been met with retracted hopes. Unless they, like us, are free to speak their own mind, unification remains but a fantasy.

The Asia House Bagri Foundation Literature Festival 2017 is taking place between 9th and 26th May. For more details, read our programme article here.