"There were plenty of fascinating discoveries"

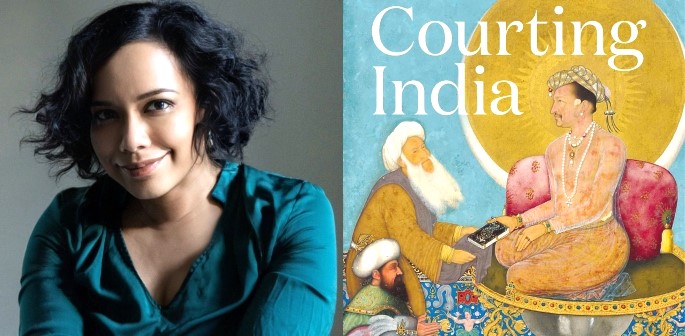

Nandini Das, a distinguished Professor and literary, has claimed the coveted eleventh British Academy Book Prize for Global Cultural Understanding with her debut masterpiece, Courting India.

Das’ groundbreaking work unravels the early 17th-century encounters between England and Mughal India and offers a narrative that transcends the Eurocentric lens.

Her book manages to reveal the complex interplay of ambitions, misunderstandings, and prejudices that unfolded.

Das’ prose, coupled with meticulous research, unveils the cultural minefields and diplomatic intricacies amid the turbulence of Mughal politics and British ambitions.

Chair of the jury, Professor Charles Tripp, describes Courting India as the “true origin story of Britain and India”.

The contrasts between an insecure Britain and the flourishing Mughal Empire, painted with Das’s beautiful writing will resonate with every reader.

But, to gather a better idea of the inspirations behind the book, DESIblitz spoke exclusively with Nandini Das to find out the importance of such a subject.

Can you share how you got into the field of writing?

I am a literary scholar by training, so academic writing of both books and articles is very much a central part of the work I do.

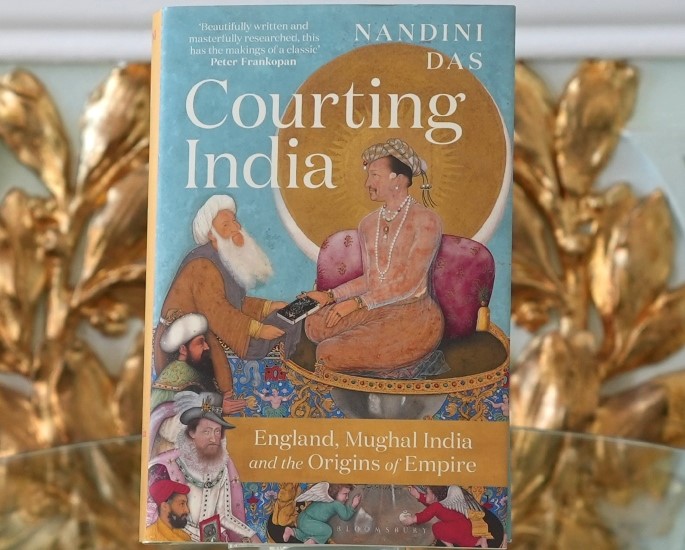

Courting India is both about a specific historical event – the first English embassy to India in the early 17th Century – and about significantly bigger questions about how cross-cultural encounters work.

So, it made me think hard about the craft that lies behind communicating both the narrative and the ideas to a wider readership.

There are simply too many scholars to name, both of literature and history, whose work has no doubt shaped my own writing style and scholarly practice.

One in particular is at the forefront of my mind, however, because we have lost her very recently.

The historian Natalie Zemon Davis, whose work on the lives of the marginalised, on people whose traces only remain in fragments, has been an abiding influence on generations of scholars, including me.

How do you feel about winning the British Academy Book Prize?

I am both delighted and deeply honoured to have received this award.

We live in a world that is currently at a point of crisis on multiple fronts.

“The prospect of global cultural understanding seems an increasingly elusive goal.”

To think that Courting India may have contributed even marginally towards that goal at some level is a wonderful impetus towards my future work.

What inspired you to delve into the origins of the British Empire in India?

Histories of empire tend to either ignore this very early period or treat it fleetingly as pre-history.

I wanted to examine how anomalous this particular period was in terms of the hierarchies of power.

And, I wanted to do this both politically and economically, when the subsequent fortunes of the British Empire were by no means a certainty.

At the same time, I wanted to explore how some of the fundamental assumptions about regions that the British would go on to colonise were formed in this period.

They were forged by conditions at home, in England, and assumed to be objective ‘truths’ that justified the imposition of colonial power and violence in the years that followed.

What motivated you to challenge Eurocentric narratives?

An encounter is never one-sided.

The focus of Courting India is on the first English embassy and the experiences of the first English ambassador, Sir Thomas Roe, in India.

“But, I look at it from the perspective of both Mughal and non-Mughal figures in India.”

However, I also looked at it from ‘interested third parties’ – the Portuguese and the Dutch, who were competitors of the English – and offered a much more complete picture.

What fascinating discoveries did you make during your research?

The research for Courting India was undertaken in multiple archives and libraries over more than a decade.

I drew on texts in multiple languages, as well as literature, visual arts, and material artefacts.

The East India Company’s obsession with paperwork is a gift for any historian, in the sense that it offers a huge archive of almost daily letters, expense reports, and journals.

One inclusion in this archive is Sir Thomas Roe’s own daily journal.

From here, it was possible to piece together a startlingly complete picture, not just of the intricate political negotiations, but the far more elusive details of everyday life.

On the Indian side, the Mughal emperor Jahangir’s memoir, the Jahangirnama, offers a striking counterpart, even when it is tellingly silent about certain things.

The relative unimportance of the English for their Indian counterparts, for instance, is illustrated by the fact that Jahangir never once mentions the English ambassador.

But, he describes the arrival of other embassies in detail.

There were plenty of fascinating discoveries along the way, some large, some fleetingly minor but equally precious.

However, one letter by an East India Company merchant singing the praises of dried mango comes to mind.

He wondered if it would find a market among English consumers in King James I’s London.

What moments shaped the relationship between Britain and the Mughal Empire?

This early period was pretty much defined by ups and downs.

The English merchants struggled to be taken seriously by the Mughal court.

This was because England was a relatively minor and belated European presence in India and because English sailors often stirred up trouble due to their behaviour in port cities like Surat.

The Mughals were also diplomatically playing the Portuguese and the English off against each other in order to ensure that neither gained the maritime upper hand.

The rhythm of Thomas Roe’s daily journal therefore tends to be one step forward and two steps back at the best of times.

“He is constantly grumbling about the behaviour of his fellow countrymen.”

Being caught in the developing power struggle between Prince Khurram (later Shah Jahan) and Empress Nur Jahan also does not help.

At the same time, in the interstices of that manoeuvring, personal relationships begin to develop.

The emperor and the ambassador, for instance, share a keen interest in art.

This leads to some of the most memorable moments of both personal and diplomatic encounters, including a striking bet about the relative merits of Indian and English artists.

But I won’t spoil that story for those who have not read the book yet.

What do you hope readers take away from ‘Courting India’?

The relationship between England and India, and South Asia in general, left an indelible mark on both nations and on global geopolitics as a whole.

Courting India marks its starting point.

Understanding what both countries and nations were to become in the future demands understanding that point of origin.

Behind that, there is a larger, more general question that I hope Courting India will also encourage readers to consider.

That is about how our assumptions and expectations about other nations and other cultures are formed, and how alienation is often a self-fulfilling prophecy.

In other words, the expectations and assumptions we inherit, either consciously or subconsciously, help to create differences.

That is not to deny the distinctiveness of cultures.

But such distinctiveness, as Roe’s embassy reminds us, does not negate the possibility of human relationships emerging across those lines of distinction.

My next book is a new history of sixteenth and seventeenth-century England, written not from the perspective of kings and queens, but that of people moving in and out of the country.

It’ll be out with Bloomsbury in spring 2026.

Nandini Das’ Courting India stands as a beacon, illuminating the corridors of history with fresh perspectives.

Das’ exceptional work reminds us of the value of international diplomacy and the intricate dance between civilisations.

As we celebrate Das’ triumph, we also celebrate the enduring power of storytelling to bridge gaps and foster understanding.

Grab your copy of Courting India here.