There are fewer than 500 psychiatrists in Pakistan

Mental health, defined by the NHS as “our emotional, psychological, and social well-being”, is something we all have to deal with.

Just as there are good and bad physical states, there are good and bad mental states.

This is something that has become common knowledge, as mental health has gained more awareness over time.

It has become a more socially accepted thing to discuss, and there has been a real appreciation of how mental health is equal to physical health.

But, despite this, mental health remains taboo in Pakistan.

According to the British Asian Trust, around 50 million people in Pakistan experience mental issues.

Due to the stigma, limited services and low awareness, 90% of those needing treatment cannot access any resources.

Additionally, a 2022 report, comparing Pakistan and China’s mental health found that between 10-16% of the population has depression and anxiety.

The same report found that 10% of the population has mental disorders. 1-2% of this is severe disorders such as bipolar and schizophrenia.

Speaking to CBT therapist Sarah Rees, she explained:

“[A] huge amount of people are struggling or experiencing poor mental health without understanding or meaning or support around it.”

This likely being as such in Pakistan, as “the harsh reality is that mental health services are painfully limited globally”.

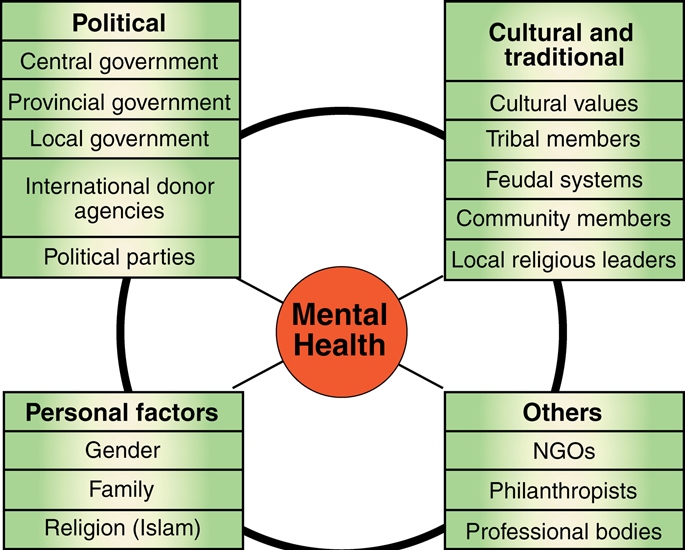

There are lots of factors involved in the “access, provision, delivery, functioning, and uptake of mental health services in Pakistan”.

This image by Aslam Bashir of Aga Khan University showcases the four main elements. These are – political, cultural and traditional, personal factors and other factors.

In the October 2020 issue of the medical journal, The Lancet, Dr Siham Sikander reflects on this, saying:

“With passing years, I have noticed many changes.

“For example, more people now seem to be aware about mental health issues, but the stigma surrounding mental health still remains.”

He also notes:

“Pakistan is home to about 200 million people, but has one of the poorest mental health indicators.”

Historically, Pakistan’s acknowledgement and treatment of mental issues have been inadequate.

Is that changing or do the reasons for this taboo still linger?

Historical Context

There is a long history of the modern discovery of mental health and the various mental conditions which exist.

There is a common perception from many westerners that mental health awareness in Pakistan must be bad, due to the idea that the ‘East’ is backwards.

However, a new discovery revealed how 9th Century Baghdad came to the earliest conception of mental health.

The Persian physician Al-Razi considered it just as important as physical health and well-being.

This just goes to show that there are nuanced and complex aspects of mental healthcare in the traditionally assumed ‘East’.

The history of the development of mental health services in Pakistan offers us a deep insight into the way mental health was and continues to be seen in the region.

In terms of the cultural and historical context, we first see mental health as heavily stigmatised.

This was ensured under the Lunacy Act (1912). It was a Colonial-era legislation focused on the detention of mental health patients in asylums, rather than treatment.

Shockingly, this particular legislation was not fully replaced until 2001 by the Mental Health Ordinance.

When the formation of Pakistan occurred in 1947, not much changed.

In fact, there were only three mental health hospitals – Lahore, Hyderabad and Peshawar respectively.

There was also a psychiatric unit at the Military Hospital in Rawalpindi. These psychiatric units were eventually established in all the medical colleges of Pakistan; especially in the 70s.

In 1986 we see a major stride in mental healthcare, as the National Mental Health Programme was established.

This programme aimed to integrate mental healthcare with primary health care.

This involved the training of primary care physicians in mental healthcare issues who were able to diagnose and support those with conditions.

The programme ensured that people could access care without needing to rely on specialists as they were inaccessible for most people.

The Mental Health Act was proposed by the Pakistani Government in 1992 after a long call for reform by medical practitioners.

However, this particular law was never passed.

In 2000, teacher training programmes started to add a mental health element nationally.

It took until the Mental Health Ordinance of 2001 for any significant change to occur. This law focused on “access to mental healthcare and voluntary and involuntary treatment”.

The ordinance also created the Federal Mental Health Authority. The focus of it was to create national standards of care for patients. It also set in place a code of practice for patient care.

Surprisingly, whilst the Pakistani government formulated the first policy on mental health in 1997, that itself was last updated in 2003.

On April 8, 2010, the Federal Mental Health Authority was dissolved.

Mental healthcare decisions are now made at the local level, by the specific provincial governments who make their own laws.

Stigma & Myths: Physical Access

Stigma is still perpetuated in Pakistan, and this is for multiple reasons. There are misconceptions about mental illness and what it is.

Stereotypical and false ideas such as having mental illness being a shameful thing are still widespread.

There are also obstacles to mental healthcare, both physical and social.

There are physical barriers to accessing mental healthcare in Pakistan, relating to the poor development of mental health infrastructure.

When mental healthcare is managed at the regional level, it can result in unequal levels of support quality in different areas.

Whilst some regions were quick to enact their own mental health laws, the same cannot be said for every region of Pakistan.

There are fewer than 500 psychiatrists in Pakistan, despite having a population of over 200 million people.

There are also only four major psychiatric hospitals in Pakistan.

There is a real lack of infrastructure, as practices have lagged behind in implementing previous reforms.

Stigma & Myths: Psychosocial Barriers

Stigma towards mental healthcare persists through other barriers to mental healthcare.

Clinical psychologist, Waqar Husain, conducted a study in 2019 in five Pakistani cities.

Looking at 3500 people, Husain found that there are nine “psychosocial” barriers. These are:

- Lack of faith in psychological treatment

- Prior personal experience

- Religious fatalism

- Carelessness for mental disorders

- Social defame

- Personal shame

- A bad reputation of mental health practitioners

- Prohibition by family

- Fear of treatment

Feelings of personal shame arose in people who feel judged when talking about their own painful emotions.

It is linked to their lack of self-esteem, self-respect and self-efficacy. Due to these feelings, they avoid seeking the help that they need.

Often, they feel as if their own issues aren’t important or that somehow it’s their fault. As a result, they don’t seek any support.

Furthermore, the bad reputation of medical practitioners was supported by different demographics.

The working class and those who were poorer tended to report this as a reason for not seeking help.

Those who were married also reported this being a reason for not getting any care.

A 2016 study found that out of 601 non-psychiatrist medical practitioners, 37% of them held supernatural beliefs surrounding depression.

It could be that ignorant practitioners are the cause of this bad reputation that leads people to avoid getting help.

Prohibition by family in this case refers to family members who ban the person suffering from getting help.

As documented by this opinion article by Saira Khan from May 2021, families would prefer to go to faith healers instead of professionals.

It’s a belief that “witchcraft, possession and black magic” causes mental health issues.

Thus, they would go to a healer to ‘remove’ the jinn or evil spirit.

Moreover, a fear of treatment stems from a lack of education about what this actually entails.

Widely, Pakistan has a mistrust of medical practitioners, which was made worse back in 2011 when the CIA used public health programmes to gain intelligence.

Eventually, this impacted the use of the Covid-19 vaccine in the country, as many were suspicious of ‘legitimate’ health schemes.

In terms of mental health, fear of treatment is also associated with the perception of getting treatment itself.

The phrase “log kia kahen gay?” which translates to “what will people say?” is all too common.

If there are societal stigmas being perpetuated, then it means people will use services less.

There is also just poor knowledge of mental healthcare and what it is.

Backing this up was a systematic review of 19 qualitative and quantitative studies on mental health perception in 2020.

In these studies, members of the public stated what they believed were the causes of mental health issues.

Most stated that these were due to “religious/spiritual, supernatural, and other ethnocultural beliefs”.

From some online discussions, it seems that there are people who would go to “traditional remedies and faith” before speaking to a medical professional.

The problem with these remedies is that they don’t look at how deep-rooted these issues are. They also heavily blame the individual and their actions as being the cause of the illness.

Collectivism vs Individualism

When researching the topic of mental health and culture, there was an overwhelming narrative.

This is that, since Pakistan is a more collectivist society, it means mental healthcare is worse.

Collectivism, in this specific context, is about how generally Pakistan is very community oriented.

The country is filled with larger connected family units, and in some sense, there is a loss of the individual.

As a result, it’s particularly concerning how familial roles may mean more than the role of the individual.

It is thus said that people put aside their individual needs for the collective family. This is including their mental health needs.

Additionally, due to this, there is more reproach towards those with mental illnesses.

But, this dichotomy between collectivism and individualism is a restrictive view of the issue at hand.

Building on previous studies, a 2022 study by Salman Shaheen Ahmed and Stephen W. Koncsol found that:

“Variations and overlap between both ideologies within a given context [exist].”

Mental health stigma can most definitely persist in those who value individualism more.

Collectivism was also not seen as a greater reason for mental health stigma.

Changing Narratives and Advocacy Efforts

The most common perceptions are that Pakistani society is incredibly stigmatising towards mental health.

Whilst this very much exists, it is not the entire picture.

A 2017 study found that the majority of Pakistanis do have favourable views of mentally ill people.

Pakistan is seeing an improvement in attitudes toward mental health illnesses.

One of the stigmas that is still perpetuated in Pakistan regarding mental health is about spiritual and supernatural beliefs.

Whilst those beliefs are still very much an issue, half the participants in the previous study by Ahmed & Koncsol perceived that spiritual possession was not the same as mental illness.

There are two most commonly proposed solutions to the current perceptions: raising awareness and improving services.

In 2019, the President’s Programme to Promote Mental Health of Pakistanis was launched.

Supported by the World Health Organisation, it has the aim of improving mental health on a national scale.

Likewise, the programme has a focus on reducing perinatal depression.

There is also the School Mental Health Programme, which is focused on getting teachers to identify the signs and symptoms of mental issues.

There has been a dramatic increase in mental issues due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

As a result, the Pakistani government published a 26-page booklet.

This booklet provides guidelines on how to deal with these psychological effects. But it is not enough.

In May 2023, there was a proposal by Waseem Hassan in The Lancet calling for mandatory mental health education.

Other organisations have also sprung up in response to the worsening of mental health since Covid-19.

One such organisation is the Pakistan Mental Health Coalition. They have published their own report on the current landscape.

Whilst it may seem dire, there are agreed-upon methods for resolving the stigma surrounding mental health in Pakistan.

These are about more awareness as well as an improvement of the services.

The situation is getting better, as more Pakistanis than ever have positive attitudes towards those with mental illnesses.

But there is a long way to go for perceptions to drastically change.

Whilst more action must be taken by the government, individually there has to be more discussions of mental health issues.